First Nations on northern Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland came together to create the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network, which provides valuable services and supports for Guardian and stewardship programs.

Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network Supports Guardians, Collaboration

Estimated Reading time

20 Mins

At a Glance

Guardian and stewardship programs are a way for First Nations to assert their presence in their territories, monitor ecosystems and cultural assets, ensure rules are being followed, and carry out cultural responsibilities.

For smaller First Nations, starting up a Guardian program is a huge – and expensive – undertaking that includes scoping and planning, hiring and training, procuring equipment and supplies, securing funding and partnerships to support community priorities, and building up the systems and protocols that guide Guardians in their work.

Through the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network, First Nations in the southern reaches of the Great Bear Rainforest are strengthening their Guardian programs and stewarding the lands, waters, and life within their territories.

Delivered through Na̲nwak̲olas Council, the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network helps to coordinate training, fundraising, procurement, and data storage for member First Nations’ Guardian and stewardship departments. By working together, Na̲nwak̲olas members are building strong partnerships, sharing expertise, and reducing costs for training and technical services.

Today, 20 Guardians, employed by member First Nations, work hard to monitor more than 3.2 million hectares on the northern end of Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland. To increase the number of Guardians and supports for member Nations’ stewardship efforts, Na̲nwak̲olas has partnered with Coast Funds to work on building an endowment that, once established, will deliver stable, consistent funding for generations to come.

Building a Stewardship Network

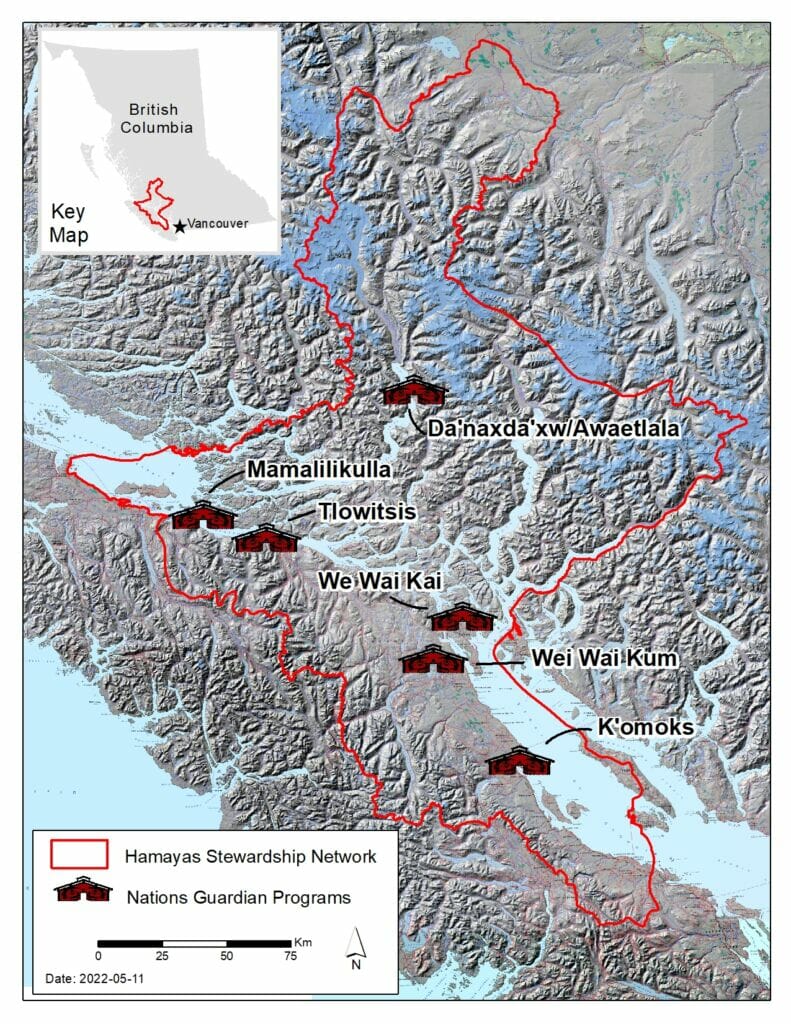

Since time immemorial, the six First Nations that make up Na̲nwak̲olas Council – the Mamalilikulla, Tlowitsis, Da’naxda’xw Awaetlala, We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, and K’ómoks – have cared for and relied upon the lands and waters of what are now sometimes called northern Vancouver Island and coastal British Columbia.

Na̲nwak̲olas member Nations’ territories cover about a third of Vancouver Island – from the Englishman River (near modern-day Parksville) to the Kokish River (near Telegraph Cove) – as well as the adjacent ocean and islands, and the mainland coast – from Bute Inlet to Knight Inlet, including the surrounding watersheds.

In Kwak’wala, Na̲nwak̲olas means “a place we go to find agreement.” In practice, that means that member First Nations make their own decisions about resource development and stewardship within their territories, and come together to share technical expertise, coordinate their efforts, and advocate as a group.

Today, Na̲nwak̲olas provides a range of services for First Nations, including support on development referrals, marine planning, mapping, forestry, and stewardship. In matters that concern all member Nations, Na̲nwak̲olas can advocate for members’ Aboriginal Rights and collective interests. Importantly, First Nations can choose whether and how they would like to work with the Council, which services they’d like to receive, and whether to engage in larger agreements facilitated through the Council.

Merv Child, a member of Dzawada’enuxw First Nation, has served as the executive director for Na̲nwak̲olas since 2009. A trained lawyer, he was called to the British Columbia Bar in 1995 and has worked with First Nations along the coast for many years, including 11 years as a member of Coast Funds’ board of directors and eight years as board chair.

“Na̲nwak̲olas was created to be a vehicle by which [member Nations] could work with the Province of BC to implement the Great Bear Rainforest agreements,” Child recalls. “That was the initial focus. But there were aspirations to grow beyond that.”

In Na̲nwak̲olas’ early years, member First Nations expressed interest in expanding their stewardship capacity in order to monitor their territories, collect their own data, and carry out conservation and stewardship projects.

“They all had aspirations of having a Guardian program, having people out on the land,” says Child. “But [individually], they just did not have the capacity to make that happen.” To build Guardian programs, Nations need trained people, stable budgets, and equipment to enable Guardians to get out on the territory and capture data.

To realize those aspirations, Na̲nwak̲olas and its member Nations considered two models: a central program with Guardians employed by Na̲nwak̲olas Council, or a stewardship network with supports for Nation-run Guardian programs. With a view to the long-term, First Nation leaders opted to run their own Guardian programs and to form a stewardship network. This approach respected each Nation’s sovereignty and decision-making authority, while also creating opportunities for collaboration and learning.

Member Nations named the stewardship network Ha-ma-yas, a Kwak’wala phrase that means “the place we go to gather food,” says Child. “That name was selected because it speaks to the territories – both the terrestrial and marine components – and the connection communities have with their territories and their importance for sustenance, life, and cultural connection.”

Today, Ha-ma-yas delivers training for Guardians, fundraises to help pay for Guardians’ wages and equipment, and provides data storage, information sharing, cost-shared expertise (i.e. marine planning, GIS analysis), and other technical supports as requested.

| HA-MA-YAS STEWARDSHIP NETWORK |

Through Ha-ma-yas, First Nations and Guardians have access to:

|

Gaining Skills to Care for the Coast

Guardians are the “eyes and ears” of their First Nation – by monitoring their territory, Guardians gather data and observations that help elected and hereditary leaders make decisions on how to manage lands, waters, and life. While they’re in the field, Guardians work to restore habitat, conduct ecosystem research, and protect their Nation’s cultural and natural assets.

Chip Mountain, a member of Mamalilikulla First Nation and father of two, has served as a Guardian for two seasons. Under the direction of his Guardian program manager, Andy Puglas, Mountain and his teammates are re-asserting the Mamalilikulla’s presence in their territories, conducting scientific research, monitoring commercial activity, and protecting cultural assets.

“It’s been a pretty amazing experience so far,” Mountain says.

In the course of a week, his team might monitor bull kelp one day, search for culturally-modified trees the next day, help contain a marine spill on the third day, and then finish the week with an archaeological survey. To juggle these different roles and responsibilities, Guardians need to develop skills and apply a wide mix of knowledge.

To build these skills, Mountain took part in the Stewardship Technician Training Program (STTP), a 20-week full-time program delivered through Vancouver Island University (VIU) in close partnership with Na̲nwak̲olas Council. The program blends classroom and field learning on water and land monitoring, communication skills, archaeological inventory techniques, forest resource management, and vessel operation. STTP cohorts are small by design, which encourages Guardians from different First Nations to work closely together and share their knowledge with classmates and instructors.

Cheryl Stone, who is Ojibway and Cree from Treaty 3 territory, works as the Indigenous development manager at VIU and works closely with the Ha-mas-yas team to customize stewardship training to fit the needs of member First Nations. Stone says that, in many ways, the training helps to reinforce the work First Nations are already doing, create opportunities for knowledge exchange, and help Guardians feel confident in their roles as stewards and watchmen.

They’re working [as Guardians] for a reason: because they want to care for their land and waters…[and] they have a commitment to protecting the territory that they’re from.

“They’re doing the work already,” Stone says. “The training gives…Guardians some of the language [they need] so that they can communicate more effectively with government bodies, marine planners, biologists…If they’re taking water samples and things like that, they know what they’re looking for and why and how that water is being sampled.”

What traits does someone need to succeed as a Guardian? “They have to want to work outside,” Stone laughs, before adding, “I think the skills and traits they need – people have them, but maybe don’t recognize that they have them. They’re working [as Guardians] for a reason: because they want to care for their land and waters…[and] they have a commitment to protecting the territory that they’re from, that they live in.”

Through their partnership with VIU, Na̲nwak̲olas Council has delivered three STTP cohorts, supporting about 50 Indigenous learners to build the skills, confidence, and connections needed to succeed as Guardians. Looking ahead, Stone says that VIU is pursuing accreditation for the STTP, so that graduates can leverage their training to pursue further education in natural resources management or related fields, if they choose.

At the end of each STTP cohort, Na̲nwak̲olas and member First Nations celebrate the Guardians’ achievement by hosting graduation ceremonies in community. Child, Na̲nwak̲olas’ executive director, says that the ceremonies are a highlight for him: “Seeing the smiles on the graduates’ and their families’ faces as they’re having their ceremony in the big house, that always makes me feel so great.”

In some ways, the STTP is an entry point or a foundational step in becoming a Guardian, says Heidi Kalmakoff, Ha-ma-yas training coordinator. “Guardians who graduated from STTP in 2015 may have different training needs now,” she says. “They may be interested in learning about project management, report writing, people management, or team building skills. At Na̲nwak̲olas, we try to be nimble and adapt to meet the evolving needs of the Guardians and Nations we serve.”

“Twice yearly, we bring all the Guardians together for three or four days to share information about their work,” says Child. At the April gathering – before the field season kicks off – Na̲nwak̲olas coordinates training activities and invites representatives from the Coast Guard, the BC Conservation Office, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), as well as experts in traditional stewardship, cultural knowledge, biology, and archaeology. In December, the Guardians gather once more to share what they’ve learned over the year and to discuss approaches to common challenges.

These gatherings and training sessions benefit new Guardians, who may not have completed the STTP yet, while helping experienced Guardians grow relationships with their peers, and with Crown government officials and experts. Because Guardians perform a wide range of tasks, they may learn a skill and use it for one or two weeks in a year, Kalmakoff says. Guardian gatherings help to keep their training up to date.

Mamalilikulla Guardian Chip Mountain completed the STTP in 2020 and “got to know [other Guardians] quite well,” he says. With Guardians busy doing the field season, “it’s pretty neat to be able to see them again [at gatherings]. It’s like a big reunion.”

At the April gathering, Mountain and his team learned how to sample soil using percussion coring to look for archaeological evidence. It’s a skill he’ll use in his work to survey Mamalilikulla village sites and clam gardens throughout his Nation’s territory.

As someone who didn’t spend much time with his people while he was growing up, Mountain places high value on the cultural training Ha-ma-yas helps to coordinate. Last April, June Johnson, a We Wai Kai Elder, showed Guardians how to identify and forage for plants, medicines, and edible berries, recalls Mountain.

“With her knowledge, she’s able to tell you the medicinal uses of it all.”

In recent years, Guardians have asked for more cultural training to gain a deeper understanding of their territories and help them carry out their stewardship responsibilities, says Scott Harris, Ha-ma-yas stewardship coordinator. “We are looking more and more to knowledge keepers to work with Guardians so they can gain those fundamental cultural teachings that are needed for their work.”

To meet that need, Na̲nwak̲olas hired Xanusa’mega Charlene Everson to connect Guardians with cultural training. Everson is a member and former elected councillor of K’ómoks First Nation and, through her network, is able to identify Elders and cultural experts who can share knowledge on traditional practices, protocols, and Kwak’wala names for places, plants, and animals.

“I am not the cultural expert,” Everson says. “I’m just somebody who has some cultural knowledge. But it’s more about connecting the right people with the right subject matter and the right application and just working on things that way.”

“I really see the value of using our own ways of doing things,” Everson explains. “What that means to me is that we’re not just, you know, doing a few things here and there that align with [our culture], but we’re trying to do our work every day [in a way that’s] aligned with our own values and our own principles.”

Language is so important. We have these concepts that live within words and they mean something.

To guide her work, Everson draws on traditional values – humility, respect, responsibility, and generosity – as well as principles and ways of being that are passed down through language.

“Namwayut. We’re all one. We’re all connected. We’re all of the land,” she says. “That’s why language is so important. We have these concepts that live within words and they mean something. There’s an importance to using those words [and] not doing a translation in English.”

“If you could speak Kwak’wala, and you had access to original place names… you would know exactly what was there before. So, if it was [called] a herring spawning place, and there’s no herring spawning going on, you know something’s probably gone wrong.”

These values and principles have helped generations of Kwakwaka’wakw and Salish people to thrive and work together prior to contact with Europeans. By bringing these values and knowledge systems into her training, Everson helps Guardians to understand who they are, their relation to their community and territory, and how communities have traditionally made decisions about stewardship and resource use.

“The Guardians are protecting our way of life,” Everson says. “They’re protecting our ways of doing things, our ability to connect with the world around us and to be a part of it.”

Those connections – to lands, ancestors, and family – underpin Mountain’s work with the Mamalilikulla Guardians. “It’s very soul-satisfying for me to be out there, to be connected with my Nation’s territory,” he says.

Since becoming a Guardian, Mountain has forged stronger connections with his people and culture, helped care for the lands and waters in his territory, and shared stories from his work with his two young children. Someday soon, he plans to bring his five-year-old daughter out on the Guardian boat to see the team in action.

Gathering Data for Decision-Making

In British Columbia, most resource and development activities (like logging, mining, energy, and infrastructure projects) proposed in a First Nation’s territory require the Province’s permission to take place. Before granting permission, the Province must consult with First Nations, and does so by “referring” development proposals to First Nation governments to consider and respond to.

Given the size of many First Nations’ territories and many development interests at play, First Nations may receive dozens of referral requests a month. To help councils manage these requests, Na̲nwak̲olas supports members with a referrals service, which provides First Nations with briefing notes to support decisions on applications within their traditional territories.

Na̲nwak̲olas maintains a confidential database for each member First Nation, housing data supplied by the Nation and its Guardians. When preparing briefing notes, the referrals team draws data from the Nation’s database, as well as from public sources, to help council members understand the potential implications of a development application.

For example, if a First Nation was consulted on a forestry tenure, Na̲nwak̲olas’ referrals team would pull public data on nearby tenures, timber volume, and traditional use, combine that with data collected by the Nation’s Guardians on archaeological sites and large cultural cedar, look up previous forestry decisions in the area, and present that information in a concise note for council members.

Ha-ma-yas does a really good job of keeping us equipped for any needs we have. They help fund us and help us buy equipment that we need, whether it be a new GPS for the boat, inReach radios, tablets, sometimes even rain gear.

To help in gathering this data, Ha-ma-yas provides Guardians with tools like drones and iPads, and delivers training on monitoring techniques and data entry.

“Ha-ma-yas does a really good job of keeping us equipped for any needs we have,” says Mountain, the Mamalilikulla Guardian. “They help fund us and help us buy equipment that we need, whether it be a new GPS for the boat, inReach radios, tablets, sometimes even rain gear. A lot of these things are quite expensive.”

Through a partnership with Ha-ma-yas, Mountain and his team are surveying historical Mamalilikulla villages and using GPS tools to mark the location of homes and food gathering sites on Mound Island. With this data, they’re able to reconstruct how their ancestors once lived.

“The house depressions…are still there,” he says. “You can see how many big houses used to be in that one village, and how big they were, and estimate how many people used to live there.”

Diana Brown, Ha-ma-yas GIS analyst, works closely with Na̲nwak̲olas member First Nations and Guardians like Mountain to maintain their databases, ensure their data is high quality and properly coded, source public data, and create maps and visualizations to support referrals and other council decisions.

“For archaeology, for instance, we have access to [data on] all the government-registered archaeology sites, so we [can] provide mapping and the locations of those sites,” she says. When Guardians are out in the field, “they use their traditional knowledge to find [and log] different sites.” When the Nation needs information on traditional use of its territory, she can combine both data sets into a custom map to support decision-making.

Brown, Harris, and other Na̲nwak̲olas staff members are working to simplify and speed up the process for retrieving data and creating maps. In the last two years, they’ve used ArcGIS Online to create secure portals for First Nations to access their geospatial data when its needed.

Beyond the referrals process, First Nations are putting this data to work, using their databases to manage resources in their territories, mitigate development impacts in culturally-significant areas, participate in marine planning and old growth deferral processes, support planning processes, and advocate for regulatory changes to protect cultural assets and ecosystems at risk.

As an example, the Wei Wai Kum Guardians gathered data over several years showing bull kelp forests in decline. Leveraging their data, they successfully advocated to have a commercial kelp harvest license revoked. In another example, Wei Wai Kum Guardians’ data was cited in a Forest Appeals Commission decision to fine a private company for illegally harvesting cedar in their territory.

Planning for the Future

Today, Ha-ma-yas provides services and funding for six Guardian and stewardship programs, which employ about 20 Guardians, most of whom work on seasonal contracts. Executive director Child points out that Na̲nwak̲olas members’ combined territories cover 3.2 million hectares and, to effectively monitor and steward those territories, First Nations will need to hire and train additional Guardians.

“You don’t have the people, the boots on the ground, to the extent that is required,” he says.

To build that capacity, Child and his team are working with member Nations to increase training opportunities and chart a path for Guardians to advance their careers and take on new responsibilities.

“We’re looking to create a professional designation for Guardians,” says Child. “In my mind, that’s the future of Guardian programs: a standardized skill set and training program.”

Harris and Everson are working to build a pathway for current Guardians to be recognized as leaders in their field through a professional title like ‘Master Guardian’ (or a similar title that’s culturally appropriate within their Nation) that’s akin to the titles held by registered professional biologists or foresters. To obtain accreditation, a Guardian would need to complete stewardship technician training, acquire cultural knowledge about their community and territory, build skills in a related field like forestry or archaeology, and have several years of experience on a Guardian team. Part of the vision for this designation is that both elected and traditional leadership could be the accrediting partner, conveying the professional title in a community ceremony in the Gukdzi big house.

With this level of training and skill, Child says Master Guardians would be well positioned to take on enforcement responsibilities and to assert their Nations’ rights and stewardship interests in agreements with Crown governments and resource users.

To realize that vision and support greater numbers of Guardians, Na̲nwak̲olas and member First Nations need access to stable, self-determined revenue for stewardship operations.

It’s not one source of funding, but many, many different sources to make it all work.

“There’s no long-term dedicated funding for [Ha-ma-yas],” says Child. On behalf of its members, Na̲nwak̲olas applies for funding from Crown governments, foundations, and other sources. Those funds, which often have deliverables attached to them, are allocated between the member Nations, who carry out the monitoring and surveying work, and share their findings with Na̲nwak̲olas, which reports back to funders.

“So much of [Harris’] job is funding to make [Ha-ma-yas] happen…It’s not one source of funding, but many, many different sources to make it all work,” Child says. “And on the other side of the equation, Nations have their own priorities apart from what they do through Na̲nwak̲olas. And the [Guardians] are out on the ground, doing things that their Nation directs them to do.”

To run their Guardian programs and complete their own projects, member First Nations draw from their Coast Funds endowments, carbon credit revenues, and their own sources, and many partner with Crown agencies and private funders to secure additional contracts and grant revenue.

“The Guardian program through my Nation is non-profit…the only way we get [external] funding is by doing [these] deliverables: the kelp survey, the archaeology, the bear monitoring,” explains Mountain.

The Mamalilikulla recently declared an IPCA in Gwaxdlala/Nalaxdlala Lull Bay/Hoeya Sound and are working to grow their stewardship authority and secure reliable financing to pay Guardians, procure equipment, and carry out projects. With limited funding, many Guardian jobs – like Mountain’s – are seasonal, which makes it tough to find and keep new Guardians.

“Nations employ Guardians from spring to fall and, in the winter, they’re let go because they don’t have the funding to keep them around all year,” says Child. “So, long-term, sustainable sources of funding would make these seasonal jobs into careers. And that would just make a world of difference. It’s hard to be a young person raising a family when you’re only working seven, eight months of the year.”

Mountain is optimistic that, with increased attention on biodiversity and Indigenous-led conservation, consistent funding will follow. “I feel that, in the next couple years, we’ll probably have corresponding funding for [more] full-time Guardians,” he says.

Long-term, sustainable sources of funding would make these seasonal jobs into careers. And that would just make a world of difference.

To that end, Na̲nwak̲olas is working with Coast Funds to explore and test options for increasing stewardship financing for Ha-ma-yas and member First Nations. That funding could come through investments in an endowment, through large-scale marine stewardship financing, or other mechanisms that aren’t tied to funder deliverables.

Longer-term, Child would love to see member Nations build up their Guardian teams to be able to self-manage their stewardship programs and development referrals. “If we could do that, they wouldn’t need Na̲nwak̲olas in a hands-on role anymore, and we’d be more of a strategic partner for them, negotiating or coordinating priorities at a higher level.”

Contacts

Using their investments with the Coast Conservation Endowment Fund Foundation, Na̲nwak̲olas member First Nations contribute to the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network.

Partnerships

- Coast Funds

- Vancouver Island University

- Marine Planning Partnership

- Nature United

- New Relationship Trust

- First Peoples Cultural Council

- Vancouver Foundation

- Real Estate Foundation of BC

- Nature Trust BC

- Pacific Salmon Foundation

- National Science and Engineering Research Council

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Online Resources

- Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network

Overview of the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network. - We Want to be Everywhere

Na̲nwak̲olas blog post: Nov. 2022. - Needed Urgently: More Trained First Nations Guardians

Na̲nwak̲olas blog post: Sep. 2022. - Growing a Powerful Group of Guardians

Na̲nwak̲olas blog post: July 2022. - All Hands on Deck

Na̲nwak̲olas blog post: Oct. 2022. - Six First Nations Work Together for Better Stewardship of Eight Million-Acre Territory

First Nations Drum article: May 2022. - Vancouver Island First Nations seek to double the size of coastal Guardians program

Global News segment: Sep. 2022. - Illegal timber harvest shows need for expanding Indigenous Guardian programs

The Province op-ed: Nov. 2022.

Published On January 20, 2023 | Edited On February 17, 2023