After a forced relocation separated the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations from their homelands, the creation of a Guardian Watchmen program is helping strengthen the Nations’ stewardship practices and cultural connections.

Return to the Homelands: Establishing the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardian Watchmen Program

Estimated Reading time

39 Mins

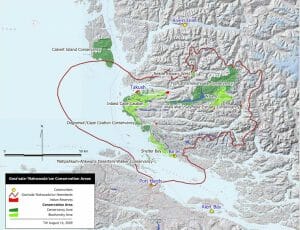

The homelands of the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw encompass Smith Inlet, Seymour Inlet and Blunden Harbour, on BC’s south central Coast.

At a Glance

“We are one with the land and sea we own,” states the guiding principle of Oweetna-kula, a concept that has directed Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations’ relationship to their territories since time immemorial.

When a forced relocation removed the Nations from their homelands in 1964, that sacred connection was broken. Decades later, when Coast Funds was created, the Nations arranged conservation financing to create a Guardian Watchmen program and reconnect to their territories.

Today, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardians play an integral role in stewarding the natural and cultural resources of their lands and waters while supporting community members to revive relationships with their homelands.

Losing a Connection to the Homelands

Before European colonizers arrived in their territories, the Gwa’sala and ’Nakwaxda’xw Nations lived as two distinct, but closely related, peoples. Their homelands covered a vast expanse of lands and waters from Smith Inlet and Smith Sound south to Seymour and Belize Inlets along the south coast of what later became known as British Columbia.

The homelands provided a wealth of resources for the Gwa’sala and ’Nakwaxda’xw peoples who based their activities and travel on the changing seasons and availability of food and resources.

The richness of the coastal region did not escape colonizers. Indian Agent George Blenkinsop described the resources of the ’Nakwaxda’xw territory in 1883: “There is a large amount of valuable timber in their country…These trees are of huge dimensions and lumber of this description could not fail of finding a ready market. The silver salmon (Coho) are more abundant in their waters than any other of the coast…and are of the very richest and the largest description.”

In 1964, the federal government forcibly amalgamated the two Nations at Tsulquate—a small reserve near Port Hardy, far removed from their homelands. Indian Agents burned down the villages at Ba’as (Blunden Harbour) and Takush before community members could return. (Read more about Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw history.)

The relocation effectively broke the connection between community members and their territories, from both a cultural and economic perspective. They immediately lost their unique and sustainable way of life.

After the removal of the Gwa’sala and ’Nakwaxda’xw Nations from their homelands, third-party development and resource extraction quickly expanded in the region. Logging, tourism, and aquaculture operations were authorized by the provincial government with few benefits returning to the community.

In the mid-2000s, when the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations first began considering the creation of a Guardian Watchmen program, most of the three generations born and raised at Tsulquate had never set foot in their ancestral homelands.

A Community Vision for Reconnection

In 2007 when the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations undertook a comprehensive community planning initiative, one of the key objectives identified was community members’ desire to reconnect to their homelands.

“One of the goals that came through really strongly [in the community plan] was to find ways to connect our community members with the homelands and get them out on the water, living off the land the way our ancestors did,” says Jessie Hemphill, a Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw member and Indigenous planning specialist who oversaw the planning process.

Chief Paddy Walkus a hereditary chief and Chief Councillor for the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw says that an increased presence and monitoring capabilities in the homelands had been a priority for several decades. “A lot came from our community on how we’d like to have better control of what’s happening there [in the homelands],” he recalls.

One of the goals that came through really strongly [in the community plan] was to find ways to connect our community members with the homelands and get them out on the water, living off the land the way our ancestors did.

The community plan that Hemphill developed for the Nations based on in-depth community consultations created a vision for how the community could regain control over their homelands. One of the ways to achieve that vision was through the creation of a Guardian Watchmen program to steward the natural and cultural resources of the Nations.

Though he was hired as the Nations’ economic development officer (and now works as the CEO of its economic development corporation), Conrad Browne was inspired by the community plan and began working on the start-up of the Guardian program shortly after he was hired by the Nations.

“The plan spoke volumes about the intensity of the desire to get the community out into the traditional territories to monitor, to ensure that resources are being extracted responsibly, to make sure that cultural components of the territories are not being adversely affected and to engage with recreational and commercial fishers,” said Browne in a 2014 interview. “That’s when the seed was planted and started to take root.”

Listening to the Elders

The Elders of the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations played a central role in establishing the fledgling Guardian program. To provide focus for the program’s activities, Browne relied on the comprehensive community plan and spent long hours listening to Elders to identify areas of concern.

Those issues were generally caused by unauthorized activities in the homelands including the illegal harvesting of endangered abalone, salmon, and undersized clams; the disturbance of important cultural and grave sites; and the poaching of monumental cedars.

Elders also addressed the need to maintain a presence on the land and waters, an objective that could be achieved through the Guardian program. “We do not have anyone there at our homelands to verify that we are the owners of the land, and that we did not relinquish our rights or title to this land, and will not now or in the future,” one Elder was anonymously quoted in a consultation report. “We need to protect and work our lands as they are ours from time eternal.”

As a newcomer to the community, Browne was not always able to access the deep cultural perspective of the Elders, but he says the general concern was clear: “They’re pillaging our territory.”

Over the early years of the program, Browne and the Guardian Watchmen continued to strengthen their relationship with the Elders, who provide an essential link to the homelands. Elders eventually began making trips with Guardians out on the water, visiting protected areas and places of cultural significance, to identify and teach them about important cultural sites, as well as traditional harvest areas and timing.

We need to protect and work our lands as they are ours from time eternal.

The conservancies throughout the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw homelands protect sites of historic and continuing cultural significance. Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary Conservancy, for example, is a protected area and home to Ẁaẁaƛ, a former ’Nakwaxda’xw village site. The management plan for the conservancy says three clans—grizzly, thunderbird, and raven—all came from Ẁaẁaƛ. It was a place where eulachon was harvested and processed into oil; where ‘root gardens’ were managed and harvested, a source for many medicinal plants; and where Chiefs would determine how much salmon would be caught each year.

Stewardship of conservancies, protected areas, marine parks, ecological reserves, and biodiversity areas in the homelands, creates the opportunity for Elders to pass on traditional knowledge to younger generations.

Connecting with Other Coastal Guardians

Before initiating their own Guardian program, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Chief and Council prioritized forging connections with other programs along the coast. Jessie Hemphill was asked to attend the annual conference of the Coastal Stewardship Network, an organization of nine coastal Guardian Watchmen programs.

In the report she produced upon returning from the conference, Hemphill identified some key challenges and lessons other Nations’ Guardian and stewardship programs had experienced. Key takeaways included the need for regular meetings to schedule and prioritize objectives; ensuring a clear and consistent vision from the outset; developing simple and applicable protocols; and connecting training to the available Guardian positions.

Browne reflects on the connections made with the Coastal Stewardship Network as invaluable. “We would not have been able to start the Guardian Watchmen program to the same extent as we did without having a direct connection into that network and some amazing human beings able to help us out,” he says.

We would not have been able to start the Guardian Watchmen program to the same extent as we did without having a direct connection into that network and some amazing human beings able to help us out.

In 2015, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardians were able to pay-it-forward when the Athabasca Chipewyan Nation arranged a learning exchange between the two programs. “I can’t speak enough of how generous [the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardians] were,” says Bruce Maclean who helped coordinate the trip. “We got direct, hands-on compliance monitoring training and went out on a tour of the territory with their Guardian Watchmen to see what they were doing out in the field.”

After Hemphill made her report to Chief and Council, the Nations submitted an application to Coast Funds’ conservation endowment fund to secure funding to launch the program and Browne was given the directive to initiate the pilot season of the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardian Watchmen.

Launching a Pilot Program

The pilot season of the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardian Watchmen program ran for three and a half months in the summer of 2010. Three community members made up the crew: Doug Johnny, an Elder with over 40 years’ experience in the coastal waters who grew up in Smith Inlet, Colin Smith, a former fisheries technician, and Leslie Walkus, who would eventually take over from Conrad Browne as manager of the Guardian program.

Browne says it was important to begin by assessing the needs and abilities of the program. The first challenge was simply figuring out the best way to access the homelands. “It’s 18 nautical miles away in some of the toughest stretches of water anywhere in the world,” Browne says. “So what does that look like and what does the vessel look like that we need, and what does the training look like that we have to have for people to operate the vessel safely?”

But they found a suitable vessel and by all accounts the initial season was a success. The crew spent approximately 1,000 man hours in the waters of their homelands, covering some 1,900 nautical miles. “Annual conservation finance from Coast Funds afforded the Nations the opportunity to return to the homelands in a meaningful and substantive way,” Browne reflected as he reported out on the pilot program.

The first trip out on the water was in mid-August. Doug Johnny provided the crew with on-boat training, teaching the other Guardians how to navigate around the traditional territories using landmarks. “At first it was a bit nerve-wracking,” Colin Smith later reported. “But after the day was over, we got the hang of it.”

People have been digging up our reserve sites for years in search of precious artifacts they can sell. However, to salvage what we do have left we must maintain a steady presence in the areas that have been hit the hardest.

That navigational training quickly proved useful as the Guardians were able to offset some of the program costs by using the vessel to transport crew and supplies to remote logging and fishing camps in the area. To this day, the Nations still share their water taxi vessels with stewardship program.

Throughout the pilot season, the Guardians focused on documenting and collecting baseline data for the cultural and natural resources in the protected areas of their homelands. In a post-season report, Smith states “Sadly enough, what we have left of our traditional territories and our reserve sites isn’t much. People have been digging up our reserve sites for years in search of precious artifacts they can sell. However, to salvage what we do have left we must maintain a steady presence in the areas that have been hit the hardest.”

Smith, Johnny, and Walkus were also able to connect other community members to the homelands. They took community members to Ba’as (Blunden Harbour) and Takush, and ensured access to food from the homelands. “We handed out food fish and made sure everyone got equal shares…on another occasion we separated elk meat into 100 portions for the roughly 100 families here and delivered it house to house,” says Smith.

The work accomplished in the initial year and those to come made an impact, not only to the lands and waters of their territories, but to the Guardians themselves. Leslie Walkus, who worked for the Guardians until 2014, spoke high praise for the time he spent on the water of Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw territories. “I could sit here for hours and talk about my job and how much I love it. To go out there in such a beautiful part of the world and to have this feeling that you’re doing something so important is a very good feeling,” he said during a 2014 interview for Aweenakola Magazine. “Being able to come home to the community and talk about the work being done, and see how much comfort that gives them—I think that’s my favourite part.”

Being able to come home to the community and talk about the work being done, and see how much comfort that gives them—I think that’s my favourite part.

Training the Guardians

One of the vital lessons from the pilot project was the need for enhanced training for the Guardians. Browne notes that there was not enough capacity in the community for trained vessel operators and this led to issues in the pilot season. “We learned the hard way that not having the properly trained personnel will cause great hardships to the program, financial as well as personal,” he says.

With support from Coast Funds, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations implemented a training program for its Guardian Watchmen. The program was designed, implemented, and managed with the support of a contractor, whose knowledge and skill base, Browne notes, were invaluable to the success of the training. The program was so successful, in fact, that the Nations were asked to share their training manual with other First Nations and industry partners.

We went from $50,000 of unexpected repairs for one vessel to $2,800 of unexpected repairs and maintenance for two vessels operating over a longer period of time.

Former Guardian, Leslie Walkus says the training, which covered everything from small motor mechanics to archeological inventory training, was an essential experience. “There’s a huge amount involved in undertaking a Guardian Watchmen program well and safely,” he says. “You really need to know what you are doing, and how to do it properly.”

The training helped the Guardians gain the trust of partners and contractors with whom they interact on the water, says Browne. And significantly, the training led to immense cost savings: “We went from $50,000 of unexpected repairs for one vessel to $2,800 of unexpected repairs and maintenance for two vessels operating over a longer period of time.”

Monitoring the Homelands

One of the most significant roles the Guardians play in the territories of the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw is working with recreational and commercial visitors. The Guardians monitor activity on the water and record non-compliance with management agreements and protocols. “Our officers will ask to see fishing licences, for example, and to have a look at the catch,” says Browne. “But perhaps most importantly, they will also talk to people if they are doing something out of line and if it’s possible, persuade them to do the right thing instead.”

Leslie Walkus, recalls those moments as intense experiences: “You have to approach people very carefully and supportively, just have a quiet word with them to help them understand why it’s important to change their behaviour.” But monitoring and enforcement are essential to the ongoing stewardship of the homelands. Conservancies throughout the region are integral cultural and ecological spaces for the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw. The Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna/Deserters-Walker Conservancy, for example, contains two former ‘Nakwaxda’xw village sites, shell middens, culturally modified trees, and is still an important site for food, social, and ceremonial harvest.

Seaweed is gathered in the spring from the rocky islands in the conservancy and is an important staple in the diet of many community members. In recent years, students from Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw school have travelled to Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna/Deserters-Walker Conservancy to learn how to harvest seaweed.

In addition to checking in on the recreational activities in the homelands, the Guardians have an important role to play in monitoring commercial activities. Chief Paddy Walkus says the monitoring work by the Guardians is essential in a territory as large as his Nations.

He points to the growing number of helicopter logging operations and drop zones in the homelands as one example. “I talked to the province who lets the permits for these drop zones and there is no real concrete monitoring device in place,” he says. “Six months after a project is done that’s when they determine if there’s any environmental impact.” Chief Walkus notes that the Guardians have monitored the work and seen some detrimental impacts in the region. He hopes that it will lay the groundwork for further monitoring and compliance efforts by the government.

David Schmidt, who previously managed the Nations’ Guardian program says he tries to get the crew out whenever a forest company completes an archeological assessment, and also partners with government research crews. “We’re trying to work with a lot of different partners,” he says. “We sent [the Guardians] out with Environment Canada to do some migratory bird studies.” The work with Environment Canada consisted of collecting and testing bird eggs for contaminants, as well as attaching trackers to various bird species and is one of several examples of research projects the Guardians are currently involved in.

Safeguarding Species through Research

Guardian Watchmen play an important role in protecting and better understanding the species of their territories. While the original intent to have the Guardians monitor the territories still continues, their work is expanding to include a wide variety of research projects aimed at protecting valuable fish and wildlife resources for future generations.

During the 2014/15 season, the Guardians partnered with the University of Victoria (UVic) to monitor the health of grizzly bear populations. That work continues to the present day.

The work takes place largely within the Neǧiƛ/Nekite Estuary and Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary conservancies and is conducted by collecting and analyzing grizzly bear fur.

The Neǧiƛ/Nekite estuary was traditionally an important seasonal harvesting area and contains a former Gwa’sala village site housing numerous smokehouses and fishing stations. As well as providing important habitat for five species of salmon, it also protects space and food for grizzly bears in the region. The Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary Conservancy is a former village site of the ’Nakwaxda’xw Nation and similarly provides important habitat for fish and bear species.

The data Guardians collect in partnership with UVic will help better understand and protect the bears and can inform a future bear viewing business, should the Nations decide to pursue one.

The Guardians also conduct research work into the populations of chum and steelhead salmon in Neǧiƛ/Nekite Estuary Conservancy. Steelhead are an important resource for the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations, both from a food, social, ceremonial perspective, and by providing potential opportunities for low-impact recreational fisheries. The fisheries work complements the ongoing grizzly studies as a healthy fish population will help to maintain a healthy bear population.

Other research includes escapement assessments of sockeye salmon at Long Lake in the Tsa-Latĺ/Smokehouse Conservancy, which has taken place in partnership with Fisheries and Oceans Canada–although in the past two years, the Guardians and the Land and Resource office have performed the work on their own. In Ugʷiwa’/Cape Caution-Blunden Bay Conservancy, the Guardians have started assessments of abalone and herring stocks. In its infancy, work has begun to assess the mountain goat populations in the territory due to its historical importance the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw peoples.

Lessons Learned

Connect with Others for Shared Learning

Undoubtedly, one of the greatest assets the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations had when establishing their Guardian Watchmen program, was connections with other First Nations. From Jessie Hemphill attending the Coastal Stewardship Network conference, to one-on-one conversations as the program progressed, Conrad Browne says the relationships formed were invaluable. “Jess Housty, William Housty, Ross Wilson, Megan Moody, [Chief Councillor] Doug Neasloss, and Wally Weber, these people were invaluable,” he recollects. “All the credit to those folks, because without them we wouldn’t have been able to get even half done what we gone done in our first year.”

Work with Youth and Elders

One of the ideas Jessie Hemphill brought back from the Guardian Watchmen conference was the concept of involving local youth in a Junior Guardian Watchmen program. In 2011, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw initiated the program which served to develop youth interest and skills, and support the development of future stewardship crew.

Equally important to a successful Guardian program is connecting with Elders, who for the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw are an essential link to the homelands. Conrad Browne learned that it is best to work slowly to develop a meaningful relationship with Elders. Though they are the keepers of knowledge, Elders may not be willing to immediately share all they know without understanding context and purpose of the program.

Training is Essential

After implementing a rigorous training program for new Guardians, the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw were able to significantly decrease costs for unexpected vessel repairs. Browne says the training helped bring a legitimacy to the program from the perspective of outside partners, and gave confidence to the Guardians who were operating the boat and interacting with industry, government, and recreational visitors to their homelands.

Learn the Legislation

Browne advises that those seeking to work in stewardship programs, like the Guardian Watchmen, become familiar with existing legislation, regulations, policies, and agreements that impact activities in a Nation’s territories. “We try to work closely with many of the regulatory agencies, with some good success with the RCMP,” says Browne. “We have a very good line of communications with all of them, especially with B.C. Parks, who have been very supportive.”

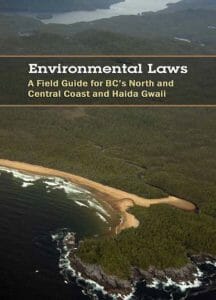

Browne says the Guardians have also been fortunate to have access to a book created by the Environmental Law Centre (ELC) at the University of Victoria called Environmental Laws: A Field Guide for B.C.’s North and Central Coast and Haida Gwaii. In 2011, working with the Coastal Stewardship Network, the ELC produced the field guide to help First Nations have a ready reference guide to the various laws and regulations in effect in their territories.

Environmental Outcomes

There are four types of protected areas in the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw homelands: provincial marine parks, ecological reserves, conservancies, and biodiversity areas. Almost 33 per cent of the territory, 92,021 hectares, is designated as protected. Each year, the Guardians monitor an average of 10,000 hectares and their work takes them through seven protected areas in the homelands.

In addition to the research and infrastructure work they’re completing, it also means an increased presence on the water. Browne says that means a public that is more aware of the potential harms of unregulated activities. “A number of comments have been very positive,” he says. “And our patrols have also put those on the fringes on notice that they are being watched and we hope that this translates into reduced harvesting and poaching.”

With the support of their Guardian programs, the Nations have published five protected area management plans for Neǧiƛ/Nekite Estuary Conservancy, Ugʷiwa’/Cape Caution Conservancy, Tsa-Latĺ/Smokehouse Conservancy, Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna Deserters-Walker Conservancy, and Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary Conservancy. Those management plans mean that the Nations are re-asserting an influence on what happens in their homelands, and protecting the resources that remain.

Learn more about management plans.

Social Outcomes

Since inception, the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw stewardship and Guardian programs have created six new permanent jobs (including a stewardship program manager, two senior Watchmen, three junior Watchmen), invested $275,217 into local, family-supporting salaries, supported members to complete 18 certifications, and provided 785 training days for a total of 31 people.

The training has ranged from general stewardship, vessel operation, first aid and safety, to leadership and administration. In a report from his time as manager of the program, Leslie Walkus said the Guardian training his staff completed through Vancouver Island University “gave the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw the tools they needed to monitor and manage the territories with a higher level of skill and knowledge.” He noted the training will help the Guardians move forward and take on more of a role when it comes to new conservation programs and initiatives.

Learn more about certifications.

Cultural Outcomes

Jessie Hemphill, a Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw member and chair of their economic development corporation says one of the most significant impacts of the Guardian Watchmen program is the role it plays in reconnecting community members to their homelands.

“Because the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations were relocated from our homelands there’s always been a lot of grief about the fact that our young people don’t grow up in their traditional territories or on the water the way they would have in the past,” she says. “It’s really exciting to know that there are at least these handful of people from our community that are growing up on the water, who are spending weeks and weeks and months out on the traditional territories, becoming familiar with them and renewing that connection.”

That reconnection expands beyond the Guardians themselves. Elders have worked with Guardians and Junior Guardians to pass on local knowledge of the territories including traditional harvest areas and timing, and areas of cultural significance. Indeed, Browne notes that the Elders are a key component in the success of the Guardian program. “The Elders are our link to the homelands,” he says.

To further help the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw people reconnect to the territory, the Guardians are front and center in helping to establish small cabins on the remote reserves. This has the benefit of providing safe harbour for Guardian monitoring trips, but more widely, provides members access to the territory and a place to stay in safety.

Learn more about Elders and youth.

Economic Outcomes

The development of the Guardian Watchmen program is supporting the diversification of the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations’ economy. Diversification into sectors like the conservation economies can help protect the Nations’ from downturn in other sectors.

Additionally, infrastructure investments from the Coast Funds-supported Guardian program totalled over $400,000, including the purchase of a vessel that is shared by the Nations’ water taxi business, and became a key transportation provider in the region.

In fact, the Guardian Watchmen program has played an integral role the development of many of the Nations’ businesses operated by K̓awat̕si Economic Development Corporation. Guardians support the Nations’ sustainable shellfish aquaculture business by helping identify areas for shellfish projects, ensuring boaters don’t dump waste in those areas, and even providing relief for shellfish farm operators when necessary. Guardians also monitor fishing in the territories, ensuring a sustainable supply of fish to the Nations-owned cold storage business.

Learn more about diversification.

Between 2009 and 2018 Coast Conservation Endowment Foundation Fund approved funding for ten separate projects totaling $1,729,309 towards Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Guardian and stewardship programs.

Partnerships

- K̓awat̕si Economic Development Corporation

- Coastal First Nations

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Deptartment

- Ministry of Environment

- North Vancouver Island Aboriginal Training Society

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Strategic Natural Resource Consultants

- Top Island Econauts

- Nature United (TNC Canada)

Online Resources

- Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations

Website for Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations - Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw History

History and Vision of Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations - Comprehensive Community Planning

Community Planning Resources and Workshops - Alderhill (now Sanala Planning)

Indigenous Planning Company - Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Comprehensive Community Plan

Summary of the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations’ CCP - k̓awat̕si Economic Development Corporation

k̓awat̕si Economic Development Corporation Webpage - Reclaiming Control: How the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw are Determining their Economic Future

Coast Funds, August 2018 - Eyes and Ears on the Land and Waters The Gwa'sala-'Nakwaxda'xw Guardian Watchmen

Aweenak’ola, September 2014 - Coastal Stewardship Network

Coastal Stewardship Network, Coastal First Nations - Coastal Stewardship Network: Collaborative Monitoring and Protection of First Nations’ Lands and Waters

Coast Funds, May 2017 - Structure of the Funds – Coast Funds

Coast Funds’ Conservation and Economic Development Funds - Environment and Climate Change Canada

Environment and Climate Change Canada Website - Neǧiƛ/Nekite Estuary Conservancy

Information on the Neǧiƛ/Nekite Estuary Conservancy - Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary Conservancy

Information on the Ẁaẁaƛ/Seymour Estuary Conservancy - Tsa-Latĺ/Smokehouse Conservancy

Information on the Tsa-Latĺ/Smokehouse Conservancy - Ugʷiwa’/Cape Caution-Blunden Bay Conservancy

Information on the Ugʷiwa’/Cape Caution-Blunden Bay Conservancy - Pacific Salmon Foundation

Pacific Salmon Foundation - Environmental Laws: A Field Guide for BC’s North and Central Coast and Haida Gwaii

Book from UVIC Law and Coastal First Nations for Guardian Watchmen

Published On November 2, 2018 | Edited On October 8, 2025