At Hada River estuary, in the heart of Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw territory, Chief Maxwiyalidizi (K’odi Nelson) is bringing an ambitious, hopeful vision to life. Nawalakw will offer cultural immersion and wellness programing supported through a world class ecotourism operation. It will be the first place on earth where Kwak̓wala is once again spoken immersively.

Nawalakw Healing Society and Culture Project: Embarking on a Journey of Cultural and Language Revitalization

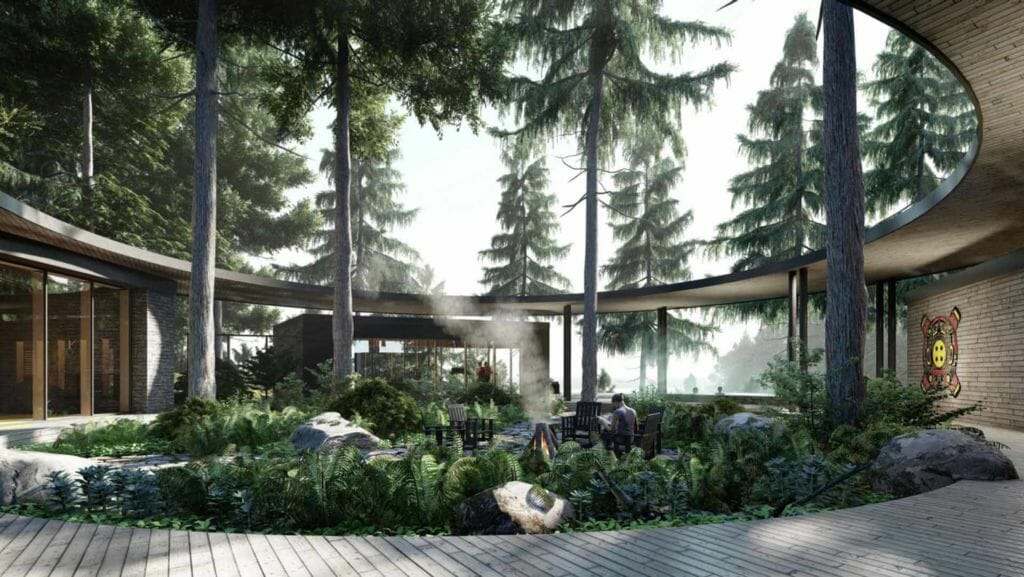

Nawalakw plans to construct its culture camp, healing village and ecotourism destination at the Hada River estuary in Bond Sound, Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw territory.

At a Glance

At Hada River estuary, in the heart of Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw territory, a vision of cultural revitalization is becoming reality. The vision is of a place where Kwak̓wala, a language on the brink of extinction, will once again be spoken immersively; a place where cultural revitalization underpins economic and social well-being. The place is Nawalakw (pronounced Now-wah-low-k, and meaning ‘supernatural’ in Kwak̓wala).

Driven by Chief Maxwiyalidizi K’odi Nelson and the leadership of Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation, Nawalakw is a ecotourism destination, healing village and culture camp that will offer healing, language and cultural immersion programs for Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people most of the year, while operating as a world class ecotourism resort in the summer months.

Nawalakw anticipates that over the next decade it will be poised to deliver more than 300,000 hours of Kwak̓wala language and cultural programing to youth and provide over 200,000 hours of wellness programming, employing up to 100 people—all while protecting and enhancing the fragile ecosystem of the Hada River estuary which will serve as a hub for the stewardship and conservation management efforts of the Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation governments.

The Nawalakw journey is just beginning. It is a bold, multi-year and multi-generational plan and participation of partners and allies will be critical for its success.

Visit the Nawalakw website to learn how you can help bring this vision to life.

Perseverance Through Cultural Prohibition

Along northern and central Vancouver Island across the Queen Charlotte and Johnstone straights, through the towering sounds and the myriad islands of what is now called the Broughton Archipelago, lies the vast territories of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw—the Kwak̓wala-speaking-peoples.

Theirs is a place of towering waterfalls, ancient forests, and an expansive coastal horizon interrupted by granite cliffs and winding fjords. From time immemorial the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw have thrived in this vast and plentiful region.

It is these lands and waters that have sustained rich cultural traditions for the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw across the millennia. “Our songs, stories, dances, and ceremonial objects honour the animals, rivers, cedar trees, salmon, and all those things that help to sustain the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw physically and spiritually,” states the U’mista Cultural Society, an organization which works to ensure the survival of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw cultural heritage.

As with other First Nations across Canada, the arrival of European settlers and the onset of colonial rule was devastating to the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw. The wealth, language, and well-being of the once prosperous Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw tribes suffered greatly under colonization, with long-lasting effects felt across multiple generations.

Kwak̓wala has been nearly extinguished. Today, only 75 fluent speakers remain and the language hinges at the precipice of complete extinction. Potlatching was outlawed, children were taken from their families and placed in residential schools where they were forbidden from speaking Kwak̓wala in programs that tried to strip them of their Indigenous identities, while introduced diseases led to the collapse and emptying of entire communities.

And yet, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw persisted. Faced with grave danger and challenges, they found clandestine ways to preserve their cultures. Some Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw carvers continued stealthily creating ceremonial objects despite the colonial prohibition. Families continued secretly speaking Kwakʼwala in defiance of the assimilationist policies and practices of the residential school system.

Today Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw community leaders continue to work tirelessly to raise community well-being, resilience, and sovereignty in their territories—leaders such as hereditary Chief Maxwiyalidizi K’odi Nelson. In 2018, Nelson founded the Nawalakw Healing Society and since then has dedicated himself to realizing a powerful vision of cultural and language revitalization and healing for all Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw peoples.

Hada River Estuary—A Place of Plenty

Throughout Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw territories are sacred, ancient sites—sites of critical importance to history, culture, and being. “These are places where our first ancestors manifested,” says Kwun Kwun Wha Lee Gei Gee-Waakus, Gwawaenuk Chief Dr. Robert Joseph, founder of Reconciliation Canada and a member of the National Assembly of First Nations Elders Council. “We were taught that if we’re from this place, then we’re responsible for this place. And we have to make sure that we protect its integrity.”

One such place for the Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w people—one of the tribal groups Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw (the four tribes of Kingcome Inlet)—is the Hada River estuary, whose name refers to a place of plenty. The estuary has provided wealth and sustenance to generations Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw.

“It’s an escape into an oasis,” says KHFN Chief Councillor Rick Johnson when he speaks of Hada. “Our people lived there over the centuries, they thrived on the abundance of seafood in the area—not only salmon, but prawns, crab, and halibut. All the essentials to survive were just right there.”

It is also the birthplace of Tsekama’yi .

The Nawalakw business plan describes the importance of Hada: “In the beginning of time when our ancestors had the ability to change forms, a man emerged from a cedar tree near the mouth of a river known as Hada. This man Tsekama’yi , had supernatural and shamanistic powers. Tsekama’yi became one of the founding members of the Ḵwikwa̱sutinux̱ people.”

In 2015, K’odi Nelson and Dadux̱wsa̱me’ Sherry Moon—both members of Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw—were working as guides with the adventure tourism company, SeaWolf Adventures. “Part of that work was getting us into the territory and being the stewards that we’re meant to be,” says Moon. “To be the eyes and ears for our people.”

One trip took them into Bond Sound where they were disturbed to find a helicopter logging operation. “It’s heartbreaking to see that kind of work being done in our territory, especially in Bond Sound,” says Moon.

That’s when I realized why the Canadian government put us on Indian reservations—that was the lightbulb moment for me. Industry is out here doing whatever the heck they want because there’s nobody here.

Nelson, too, was saddened and angered by seeing the logging operation in a place where Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw had gone to prepare salmon for 10,000 years. “That’s when I realized why the Canadian government put us on Indian reservations—that was the lightbulb moment for me,” Nelson says. “Industry is out here doing whatever the heck they want because there’s nobody here.”

For Nelson, this was a call to action. The impacts of colonization, the reserve system, and residential schools had left his people with little or no presence throughout their territories. He recognized an opportunity to reverse the situation he saw in front of him by getting Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw peoples out onto their lands and waters. “We have to get something built here,” he remembers thinking at the time. “So that was the start of it.”

Visioning, Planning, Building—From Dream to Reality

Nelson knew he had to find a way to build something on the Hada estuary. Initially, the idea was just to create a simple cabin. But the more he thought about it, and the more he heard from community members what they needed, the more the idea grew.

From a cabin, to a floating lodge, to eventually Nawalakw Culture Camp, Healing Village and Lodge: a dual-purpose ecotourism lodge and place to foster traditional teachings in all aspects of the Kwakwaka’wakw culture. “The ideas and our vision are still growing,” he says.

Chief Councillor Johnson says the plan Nelson has developed gelled well with the one Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation (KHFN) had formed. “We had developed a community plan that we were going to use tourism as a way to create jobs and self-esteem,” he says. “And K’odi came up with this unbelievable plan. That sort of married into our plan for the future.”

The vision outlined in Nawalakw’s business plan is powerful: “Nawalakw will become the first place on earth where Kwak̓wala will once again be spoken immersively, sparking a revival of language and culture throughout Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw territory. It will be a place where Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw language and culture leaders, and leaders in Indigenous health and wellness, can gather, mentor and educate.”

“Nawalakw represents medicine for our people,” says Nelson. “And it represents a deep connection to the values taught by our ancestors about how to live and thrive in unity with nature and with each other.”

Nawalakw will become the first place on earth where Kwak̓wala will once again be spoken immersively, sparking a revival of language and culture throughout Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw territory.

Chief Robert Joseph—who has supported and advised on the Nawalakw project—describes the project as an opportunity for a new beginning for Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw . “It means we can begin to get back to learning and recreating a relationship with our territories,” he says.

Chief Robert Joseph—who has supported and advised on the Nawalakw project—describes the project as an opportunity for a new beginning for Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw . “It means we can begin to get back to learning and recreating a relationship with our territories,” he says.

To bring that vision to fruition, Nelson found strength in partnerships he formed with friends and community members. He formed a small team consisting of Hamish Rhodes, a friend and architect (adopted member of a Mamalilikulla First Nation family); Dawn Nicolson, an economic developer from Dzawada̱’enux̱w First Nation; and Duncan Kennedy, an experienced entrepreneur of Métis decent. Together, the team was able to raise initial funding from the federal government to conduct a feasibility study.

In 2017, Nelson met Coast Funds staff Ashley Hardill (Director, Project Investment) and Brodie Guy (CEO) while the pair were in U’kwanalis Kingcome Village where they had been invited for a community economic development meeting by Dzawadaenuxw First Nation. Hardill and Guy immediately connected with Nelson’s inspiring vision.

By 2018, discussions between Nelson, the council of Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation (KHFN), and Coast Funds had developed towards a first investment of funds by KHFN from their economic development allocation with Coast Funds to support the predevelopment phase of the project. This early predevelopment phase focused capital and business planning; securing the necessary tenure, permits, and licenses; and developing impact assessment reports.

The following spring, Nelson found himself at Nimmo Bay presenting that vision to a small group of funders. The event turned out to be the first in a series of doors that swung wide open to facilitate the growth of Nawalakw. Before the day was through, and much to his surprise, he had secured a major investment from an anonymous family foundation. In recalling the moment that first investment offer was made, Nelson still speaks in astonishment. “You can imagine, it was like winning the lottery – it felt very surreal.”

You can imagine, it was like winning the lottery – it felt very surreal.

Paddling Toward Positive Change—Starting the Journey

In the short time that has since elapsed, Nawalakw has transformed from the stuff of dreams to a real, capitalized project now entering its second phase of development. The Nawalakw vision is being uplifted by many visionary organizations and individuals who share the vision and support the mission. Following the first anonymous donation, Nelson connected with another anonymous family foundation, and the Mastercard Foundation, who are supporting educational and training opportunities.

“The Foundation is honoured to do our part to support the Nawalakw Healing Society in their work to strengthen their language and culture in a way that fosters opportunities for their youth and a green, sustainable economy,” says Jennifer Brennan, Head, Canada Programs at Mastercard Foundation. “They are showing that the way forward will always be found in the vision and values of Indigenous communities, youth and Nations.”

Nelson’s day-to-day has similarly taken a dramatic shift. Shortly after receiving that first investment, Nelson left his teaching career and now works full-time as the executive director of Nawalakw. He now dedicates all of his time and energy towards bringing his ambitious vision for the Nawalakw project to life.

They are showing that the way forward will always be found in the vision and values of Indigenous communities, youth and Nations.

“The fire has been lit and I look forward to fueling it with the energy and love required,” wrote Nelson in a 2019 email. Nawalakw had just gathered a small group of partners together at the G̱waʼyasda̱ms big house on Gilford Island to uplift the Nawalakw Vision. “I believe that this is going to happen and with all of you in our canoe we will get there.”

Once completed, Nawalakw will operate as a ecotourism destination on the banks of the Hada River. From June to September, the lodge will welcome ecotourism visitors from around the world, offering people the chance to be immersed in Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw experiences, and will also offer a one-of-a-kind dining experience rooted in local and ancient harvesting techniques.

For the majority of the year, the lodge will operate as a healing and wellness centre, providing language and cultural programming. In addition, as expressed in the project’s mission statement, “Nawalakw will be a place for Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw communities to meet, maintain and foster traditional teachings in all aspects of their culture, beginning with the origin stories, to fishing, foraging, traditional harvesting, language immersion and spirituality for generations to come.”

Reconnecting with the land is essential for the well-being of Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw members, says Moon—who now works as the Culture Project Training and Employment Manager for Nawalakw. “I truly believe that you don’t really know where you’re going unless you know where you’re from,” she says. “Our culture, our language, who we are—it all comes from the land.”

The transformation of Nawalakw from vision to reality is taking place in three phases. Phase One will see the construction of a culture camp completed. By Spring 2021, Nelson expects the culture camp to be fully constructed and operational as a language revitalization centre that can house up to 24 students, their teachers, and up to 12 support staff. Already the centre has received expressions of interest for group bookings and soon Nawalakw will become a place where Kwak̓wala—a language previously on the brink of extinction—will once again be spoken by youth and Elders alike.

Our culture, our language, who we are—it all comes from the land.

Initial plans for Phase Two include a healing village designed to provide early immersion language, training and certification programs, as well as healing programs in partnership with BC First Nations Health Authority with a lodge, individual cabins, a wellness centre and outdoor facilities. And Phase three will be an interpretive centre, retail space, and gallery showcasing local artists, as well as housing for those doing stewardship programs at Nawalakw. Though Phase One is nearly completed, the next two phases are expected to require significant additional funding. Nelson and his team are continuing to raise funds.

“Nawalakw really appreciates that support,” says Chief Robert Joseph. “This can really only come to fruition with the goodness and generosity and kindness of other people who care about humanity in a collective way.”

In Nawalakw’s first community newsletter, Nelson writes, “We’re creating a social venture that brings jobs to our community, creates a presence and environmental stewardship in our traditional territory, funds healing and language revitalization programs, and creates pride in our children, and our children yet unborn.” It’s a bold vision and one that Nelson hopes to see replicated. “We believe this business model will be replicated by other Indigenous communities anywhere else in the world.”

Working Together—Allies for Understanding

As the building site is located on the Hada Estuary, the traditional territory of the Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w, now amalgamated under the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation, their community members and Council are the primary project development partners. Integral to the project’s design, however, is the creation of a terrestrial route between Nawalakw Lodge and the neighbouring community of U’kwanalis Kingcome Village, a permanent year-round community of the Dzawada’enuxw First Nation (DFN).

The route will provide U’kwanalis residents with access to employment opportunities at Nawalakw. The Nawalakw business plan explains that, “establishing this linkage is vital from an economic point of view but also symbolically important as it crosses an artificial divide separating Dzawada’enuxw and Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis, ultimately strengthening economic and social ties between communities.”

The intention to create both figurative and material bridges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, as well as across First Nations, is a key element of the project’s high-level ambitions, explains Nelson. “First Nations have a lot to offer the bigger world in how to protect areas like this and how to look after it, how we’re all interconnected,” he explains. “So that’s going to be the bigger message–it’s all about gaining allies….allies for understanding each other and allies for protecting Mother Earth.”

Chief Joseph echoes Nelson’s sentiment, describing how the Indian Act forced separation between tribal alliances. “We truly did have an affiliation among the Musgamagw tribes. And so, this project, when it’s successful, will bring us together again.”

First Nations have a lot to offer the bigger world in how to protect areas like this and how to look after it, how we’re all interconnected.

Saving Kwak̓wala For Future Generations

Nawalakw is envisioned as a place of healing, community empowerment, and, once up and running, will be the first place on Earth where Kwak̓wala is spoken immersively. The goal of reviving Kwak̓wala, by offering on-site language immersion programs adds a level of urgency to the plan.

“We’re down to probably a handful of our first speakers and they’re all in their 80s and 90s.” says Chief Councillor Johnson. “Something like this should have happened 25 years ago.” By Nelson’s estimation, there are only about 10 years left before the few remaining Elders who are fluent in Kwak̓wala are gone forever

You have to start with [language] first, everything else will build from that. They’ll be good at math and English and all that other stuff. But if they’re not feeling good about themselves, they’re not going to be good at any of that. That’s what this project is going to do for our People.

To Nelson, imagining the positive spin-offs of what it would mean to achieve language fluency amongst Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw youth serves as a powerful source of motivation. To him, language is the catalyst to needed community healing and to the development of cultural pride and identity amongst Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Peoples.

“You see how much trauma we’ve dealt with and continue to deal with—all forms of ongoing colonization, from the potlatch prohibition to the residential school systems to the Indian Act,” he says. “These intergenerational traumas have caused unbalance in our physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental wellness. Those trauamas have an economic cost. I believe that our culture is going to be what heals our people from those past experiences.”

As a former schoolteacher, Nelson has witnessed firsthand the transformative power that learning traditional languages can have on Indigenous children. “You have to start with [language] first, everything else will build from that,” he explains. “They’ll be good at math and English and all that other stuff. But if they’re not feeling good about themselves, they’re not going to be good at any of that. That’s what this project is going to do for our People.”

Pivoting to COVID-19 Relief Efforts

In 2020, Nawalakw was faced with a massive obstacle: the COVID-19 pandemic that would temporarily shutter ecotourism businesses across the coast. The society had secured training placements for youth at Nimmo Bay and other nearby resorts, but the COVID-19 Pandemic put an abrupt stop to those positions.

Unwilling to lose momentum, the Nawalakw team pivoted. “We had about 16 to 20 positions lined up for youth, but four out of five resorts had to close because of COVID,” recalls Moon, whose job involved overseeing the placements. “We had to pivot.”

Instead of resort training, the youth and a number of others from the Nawalakw network shifted to providing support for the Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw communities. Youth completed projects focusing on improving food security and distributing supplies of personal protective equipment such as masks and hand sanitizer.

Since April, youth hired by Nawalakw have built 120 garden boxes for members in the community of Alert Bay. The project involves building the garden boxes, filling them with fertile soil, delivering and planting the seeds, fruits and vegetable starts, and continuing upkeep.

The youth also spent time at Hada clearing trails for a blessing ceremony to celebrate the start of construction for the culture camp. Jonah Johnson, Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw youth spoke in the Nawalakw newsletter of the experience, “I felt like I had been there before. We went to check out the river and check out the site. We were able to see K’odi’s vision while we were there. We spent the whole day in Bond Sound clearing trails, making it easier for elders, clearing trails to make pathways clear for them to walk.”

Our Rivers Were Never Meant to be Alone: A Blessing Ceremony at Hada

The blessing ceremony Johnson and the others had worked toward took place on in the spring of 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic added extra complications, but the event was able to take place. “Getting a group together for a blessing while following all the safety protocols was a good challenge,” says Nelson “We were only able to invite a small number of our youth, our hereditary leadership, our Elders, and our ancestors. But it was an important milestone for us to acknowledge.”

Nelson recalls the day as a powerful milestone where ideas were finally becoming concrete “For the very first time throughout this whole process I felt this big lump in my throat. This was the first physical sign that we’re actually doing this. I was like ‘We’re actually having a blessing today because we’re going to start building soon.”

Our rivers were never meant to be alone. We recognize the role of our land as a teacher and healer, guided by our ancestors and our Elders.

Chief Dr. Robert Joseph attended the event. “Our rivers were never meant to be alone,” he spoke. “We recognize the role of our land as a teacher and healer, guided by our ancestors and our Elders.”

The day was one filled with promise, hope, and unity says Nelson. It was a day for future generations. Children from Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw communities conducted the blessing, something Nelson says he has never seen done before. The decision was in part due to COVID-19 restrictions, but he says it turned out to be the right decision. “In a way it was almost perfect because from day one we’ve been telling our funders, we’ve been telling everyone that this is for our kids and our kids yet unborn. So, it was fitting that they were the ones that blessed the ground.”

Lessons Learned

While only a few short years have elapsed since he began outreach and partnership development to begin the process of building the Nawalakw vision, Nelson has been on journey of learning and has generously shared the following key takeaways:

Timing

One challenge we faced early on was the need to move quickly in securing funding and putting the plan into action. There are few fluent speakers of Kwak̓wala remaining and we really wanted to start operating immersion programs as soon as we got started.

Power of Relationships

Through this process we’ve gained a greater appreciation for the power of reciprocal, high-trust relationships. There are a lot of people out there who want to help and we’re deeply honoured and blessed that people trust Nawalakw to carry out this work.

We are totally firm believers in our business model–that this model could and will be used all across the world. So, we want to do it properly, and we’re going to make many mistakes along the way. But so long as we accept that and just keep moving forward and learn from our mistakes, we’ll continue to grow and improve.

Challenges of a Remote Location

The Hada River estuary is the perfect location for the Nawalakw complex, but it comes with a number of challenges. The remote and unserviced nature of the area means significant infrastructure investment, high costs for transportation, and additional fees added for barging in supplies.

We employed 43K Wilderness Solutions, to consult on building in the remote location. In a short post about the project, they wrote about the “unique environmental and geotechnical considerations” of the project.

We’re committed to hiring local First Nations individuals and businesses. The construction bid was won by Gala Construction, a First Nations owned-and-operated company from Alert Bay.

Gala Construction will use ideas like sourcing local gravel, designing unique road specifications to minimize impact, and reducing transportation costs by using a design that requires fewer materials.

Cultural Outcomes

In the next decade, Nawalakw expects to deliver more than 300,000 hours of language and cultural programming to Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw youth.

Deeply, immersively learning one’s language and culture is an important process of decolonization, says Chief Dr. Robert Joseph. “The language in itself is a lesson. Not just speaking or talking, but having real inherent values that are important for all Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw and hopefully, other people who are interested.”

That’s exactly what he envisions for Nawalakw: “We’re going to relearn our culture and our traditions. For young Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people we’re going to be working really hard to restore their dignity and pride, so that they know exactly who they are.”

Sherry Moon can attest to the power reconnecting to the lands and waters in her territory, and the power of Nawalakw. “Doing the work that I do with them has transformed my life,” she says. “I used to be this really shy, closed up person. And now I’m just completely different.”

Nelson trusts time spent at Nawalakw will be life-changing for those youth and others who visit the centre. “When you go to Nawalakw, you’re going to leave transformed and your thought process is going to be different,” says Nelson. “Your heart and your brain and everything about you will be different when you leave.”

Environmental Outcomes

From the outset, the planning of all phases of the Nawalakw project has always been guided by a strident ecological ethos. “We can’t just talk the talk, we gotta walk the walk,” says Nelson. “From very early on we wanted to be as green as we possibly could.”

The Nawalakw business plan outlines several measures intended to minimize the use of fossil fuels while maximizing the use of clean, renewable energy. Every aspect of the project, from wastewater management to transportation to architecture, has been designed to protect the fragile ecosystem of salmon and grizzly bears in the Hada River estuary. “Our ancestors, they preserved all of that for us,” says Moon. “And now it’s up to us to look after it. And in turn, it will look after us.”

Inspired by the Nawalakw vision, architect Jason McLennan (of McLennan Designs) provided guidance on how to make the project as green as possible. McLennan is the creator of a building code called “The Living Building Challenge” where structures are designed and built to produce more energy that than they consume. “We’re very fortunate Jason has volunteered his time and energy,” says Nelson. “He was blown away with the vision and wanted to be involved.” Nelson is hopeful Nawalakw will be the first ”Living Building-certified” ecotourism destination in the world.

Nawalakw will also serve as a hub for local Guardian Watchmen who are employed by their Nations to serve as environmental stewards and monitors of their territories. The facility will also be open to host research activities and regional training and certification programs with a focus on capacity building to ensure the sustainability of this region.

Social Outcomes

“This might be a way to bring our people home,” says Chief Councillor Rick Johnson. Like many remote First Nations communities Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw members often relocate to bigger cities to find work.

“Losing our children to the cities—it takes the heart out of the people,” says Nelson. “When we see communities getting smaller because we see people leaving to go find jobs somewhere else.”

The communities of Musga’makw Dzawada’enuxw are “really small” says Chief Joseph. Reconnecting community members with their territories is essential “so that every Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw child has a sense of who they are, where they come from, where they belong, what their families and communities represent, and how they should grow up to be good human beings.”

For that reason, Nelson anticipates the employment opportunities offered by Nawalakw to be significant. Nawalakw is expected to employ up to 100 part-time and full-time staff, prioritizing hiring from local First Nations. Already, Nelson reports, Nawalakw has been able to hire 16 employees and contract positions, 19 seasonal youth workers, and indirect local construction jobs have also been created. “The economic spinoff for our communities has already been huge,” says Nelson.

The social impacts of the project are immense, says Chief Joseph. “Some of those things are so important and critical to allowing us to grow up feeling loved, that we belong, and that we’re respected,” he says.

Through the development of Nawalakw, Nelson and KHFN leadership received leadership, management, and business planning training. Nelson also points to extensive social entrepreneur training he has received with the support of Indigenext.

Economic Outcomes

“The visitors who will come here will experience the unique beauty of our people and our land,” said Chief Dr. Robert Joseph at the blessing ceremony for Nawalakw. “But more importantly this project will help create economic development deeply rooted in our culture and ensure our traditions live on in our young people for generations to come.”

Partnerships have been an important outcome of the project, with so many organizations and individuals coming together to uplift the Nawalakw vision. Including, First Nations partners, major funders, youth employment and tourism partners, design and development partners, and all levels of colonial government. Nawalakw is grateful to all those who have contributed their time, talent, treasure, and ties to the success of this journey.

Uplift the Nawalakw Vision

This is just the beginning of the Nawalakw journey. Nelson invites supporters to join him through the next phases of development. Though Phase One is nearly complete, Nawalakw is seeking funding to bring to life the healing village and ecotourism destination that will fund the culture camp (Phase Two) and the interpretive centre, retail space, gallery, and stewardship centre (Phase Three).

The Nawalakw vision is a bold, multi-year and multi-generational plan. The participation of partners and allies is critical for its success.

Nelson carries with him a small carved canoe filled with the hand-written commitments of Nawalakw’s partners and supporters. He often pulls it out to remind himself and others of the commitment to see the journey through to completion.

“We’re going to need everyone paddling on this journey,” he says. “And we’re looking for caring people who want to join us in our canoe.”

Find out how you can contribute to bringing this powerful vision to reality by visiting the Nawalakw website or contacting K’odi Nelson.

We’re going to need everyone paddling on this journey. And we’re looking for caring people who want to join us in our canoe.

In 2018 and 2019, Coast Funds’ Board approved funding towards the pre-development of the initial planning and implementation of the Nawalakw project’s vision. Coast Funds continues to work in support of Chief Maxwiyalidizi K’odi Nelson when and as requested towards realizing the full vision of Nawalakw. Learn how you can play a role by visiting the Nawalakw website.

Partnerships

- Nawalakw is immensely grateful to all who have come together to uplift the vision. The list below represents many of the partners and friends who have contributed their time, talent, treasures, ties, but is by no means exhaustive. Many others have been a part of the Nawalakw journey and will join in the coming years.

- Dzawada'enuxw First Nation

- Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation

- Hereditary Chiefs of the Musgamakw Dzawada'enuxw

- Coast Funds

- Impakt Foundation

- Island Coastal Economic Trust

- Mastercard Foundation

- Proctor and Gamble

- Shorefast Foundation

- Government of Canada

- Government of British Columbia

- BC Parks

- Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development

- A̱ka̱la Society

- Blue Ocean Consulting

- Coco Cafe

- Farewell Harbour Lodge

- Global Medic

- Hamish Rhodes

- Hemmera

- Indigenext

- Iskwew Air

- Legacy Tourism

- MakeWay

- McLennan Designs

- Nimmo Bay Resort

- Sea to Cedar

- SeaWolf Adventures

- Soap for Hope

- The Wickaninnish Inn

- ViH Aviation

- YoBro YoGirl

Online Resources

- Nawalakw Healing Society

Nawalakw Healing Society website - Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation

Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation website - Dzawada'enuxw First Nation

Dzawada'enuxw First Nation website - Gwawaenuk First Nation

Gwawaenuk First Nation Information - Hunwadi/Ahnuhati-Bald conservancy

Hada River estuary is in the same area as Hunwadi/Ahnuhati-Bald conservancy - Our Land - Kwakwaka'wakw Territories

The territories and First Nations of the Kwak̓wala-speaking peoples - Our Language – Kwak̓wala

Kwakwaka'wakw means Kwak̓wala speaking peoples - The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit

Data from 2016 Federal census - Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw artists

Kwakwaka'wakw artists at the Stonington Gallery - SeaWolf Adventures

Adventure tourism led by Mike Willie of the Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis - Our Future - Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis

Comprehensive Community Plan for Ḵwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis - Nimmo Bay Resort

Resort in Kwakwaka'wakw territory - Sea to Cedar

Partners with Nawalakw Healing Society on youth programs - A̱ka̱la Society Youth Programs

Two youth padding programs in partnership with Nawalakw and Sea to Cedar - Nawalakw Covid Relief Project

Nawalakw Covid Relief Project Facebook page - Reconciliation Canada

Reconciliation Canada website - Assembly of First Nations Elders Council

Elders Council for the Assembly of First Nations - Case study: Nawalakw Cultural Healing Centre

43K Wilderness Solutions - Nawalakw Summit at Nimmo Bay Resort

Love + Regeneration Magazine, Issue 2 - Nawalakw Lodge: Early Building Conceptualizations

Visualizations by designer Hamish Rhodes - Taking the Nawalakw Culture Project from Vision to Reality

MakeWay, 2020 - Realizing a Vision for Nawalakw Healing Society

Coast Funds, July 2019 - How a BC Indigenous Community Is Creating a Micro-economy Through Wellness

Nuvo, January 2021

Published On January 27, 2021 | Edited On February 26, 2025