On northern Vancouver Island, We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, and K'ómoks carvers are sustainably working with western red cedar, creating cultural artworks that celebrate the revival of ancient traditions. Working in partnership with Na̲nwak̲olas Council, the Nations protect wilkw / k ̓ wa’x̱ tłu Large Cultural Cedar, balancing ecological stewardship, community well-being, and the protection of biodiversity.

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Carvers Uphold Millennia-Old Traditions

Estimated Reading time

43 Mins

We Wai Kai’s Quinsam Reserve is located in northwestern Campbell River on the central east coast of Vancouver Island. In the Salish language, Quinsam means “resting place.”

At a Glance

On northern Vancouver Island, We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, and K’ómoks carvers are utilizing wilkw / k ̓ wa’x̱ tłu Large Cultural Cedars (LCCs) to create traditional canoes, poles, Big Houses, and other works that celebrate the cultural vitality and ancient traditions of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw First Nations.

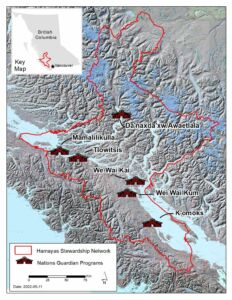

Guardian programs like those connected through the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network, supported by Na̲nwak̲olas Council, help the Nations’ Guardians to survey and inventory LCCs within their territories, data which is then entered into an LCC database housed by the Nanwakolas Council. Member Nations use this data to guide decisions about the protection and harvesting of LCCs for cultural use in cutblocks and other forestry stewardship decisions.

The LCC inventory helps carvers See-wees Max Chickite, ƛ̓aqwasgəm Junior Henderson, and Długweyaxalis Karver Everson to source rare old-growth, western red cedar that are of high wood quality and suited for carving for their projects. Working on their latest ocean-going xwax’wa̱na canoe, the carvers mentored four apprentice carvers, passing their ancestral knowledge and skills on to the next generation.

Carving A New Path: Continuing Traditions of Ancestors Past in Modern Times

We Wai Kai’s Quinsam Reserve, located near Campbell River, BC, is surrounded by indigo-blue skies. It’s a hot summer’s day in July, but that hasn’t stopped Max Chickite from working on his latest carving project in front of his home. His project is a collaboration between carvers from We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, and K’ómoks First Nations: they are carving an ocean-going xwax’wa̱na canoe.

For thousands of years, First Nations in this part of the world have built and used canoes for transport, hunting, and cultural traditions.

Max takes a break in his deck chair to watch two other carvers, Junior Henderson and Raymond Shaw, continue carving out chips of wood, smoothing out the sides of the canoe. Max picks up a hand-crafted D-shaped adze to demonstrate. He holds the D-shape of the handle in one hand and swings his forearm down in a vertical chopping motion.

“I just made this tool yesterday. You can’t get this at the store – they don’t sell these at Home Depot.”

Max’s adze is modern version of a traditional tool used by First Nations people to carve canoes, house posts and planks, poles, and household items. It has a solid weight to it and the blade is about as long as Max’s hand.

Max, a proud Liǧʷiłdax̌ʷ man and We Wai Kai citizen, learned his carving skills from his family, friends, and through years of work experience.

“My grandfather was a boat builder,” says Max. “His friends had lots of different tools. They made their own hand planes with five to seven degree angles and carved blocks of wood. Some of the guys were carvers back then, even though they weren’t allowed to carve. They still taught some of us.”

I remember, I went to a Potlatch up in Alert Bay and I saw the masks that were being danced. I knew that’s what I was going to do.

In the late 19th century, the Government of Canada considered Indigenous cultural activities, like carving and potlatching, an obstruction to their goal of assimilation, and so passed several policies designed to abolish cultural practices, including the 1885 Potlatch Ban. At the same time, many First Nations children were forcibly removed from their families and placed into residential schools, preventing cultural activities and languages from thriving. The Potlatch Ban was upheld well into the 1950s and the last residential schools in Canada continued to operate as late as 1996. During this time, many First Nations were unable to continue their cultural traditions and were prosecuted for doing so.

Max’s grandfather, Edward Chickite, mostly carved masks, which his family kept hidden from the eyes of Indian Agents. Max recalls that when he was a boy, his family would continue to keep parts of their culture hidden, including speaking Lik̓ʷala, out of both fear and respect for “the suits.”

“I gave [my grandparents] masks, as special gifts, to hang them on the wall. But they would hide them because language and Potlatches were banned. So [the masks] were all hidden in a room – there was boxes of them.”

Slowly, as First Nations revived cultural practices like Potlatches, Max was able to embrace his family’s traditions, learning from others along the way. Max was in his early teens when he carved his first mask.

“It was a wild woman, for a Potlatch,” he recalls. “I fished up and down the coast, so I got to stop in villages and go see whoever was carving around in the village. I’d chat with them, watch them. I remember, I went to a Potlatch up in Alert Bay and I saw the masks that were being danced. I knew that’s what I was going to do.”

Back at Quinsam Reserve, Max smiles over at the ten-metre-long canoe, which was later given the name G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala at a canoe launching ceremony. The carvers are working steadily, drawing blades over the wood in swift, practiced motions under the hot sun. Working with traditional crooked knives, they slice thin layers of cedar wood from the starboard side, smoothing out the exterior lip of the canoe’s gunwale. With each stroke, feather-light cedar shavings fall in coils at their feet and the summer air grows heavy with the tang of cedar.

“This is Max’s dream project,” says Max’s friend, Bill Goodman, as he watches Max, Junior, and Raymond working on the canoe.

Only weeks before making its journey to Max’s home, this canoe was still a windfallen Large Cultural Cedar (LCC). Estimated to be over 400 years old, the cedar lay in the H’kusam forest for about ten years before the carvers selected the log suitable for their project.

When it’s time to flip the canoe, Max puts his travel mug down and helps the carvers hoist and rotate the canoe using A-frame rigs and chain pulleys. The process is slow and meticulous, with the carvers communicating to each other at every turn until the canoe is belly-side up. This task, Max says, would have taken about 30 people to do by hand.

“Easily the whole village back in the day.”

Protecting Large Cultural Cedar in Wei Wai Kum, We Wai Kai, and K’ómoks Territories

Many of the carving projects found around Quinsam Reserve and across northern Vancouver Island are made using highly valued old-growth western red cedar, an increasingly scarce resource that has sustained First Nations’ forestry economy across British Columbia for thousands of years. Called the Tree of Life by Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw peoples, cedar is vital to the well-being of the First Nations that have always cared for the health of the forests and trees in their territories, ensuring sustainability and balance.

First Nations have maintained a sustainable forestry practice for thousands of years, selectively harvesting whole trees (to build large structures like Big Houses, totem poles, and dugout canoes) as well as parts of trees by stripping, planking, and carving living poles (to craft items like clothing, bentwood boxes, and rope).

First Nations selectively harvested trees with traits that make them suitable for carving, such as minimal knots, minimal heartwood decay, straight and tight wood grain, and minimal stem tapering.

In recent years, large red and yellow cedars have been protected and monitored by member First Nations of Na̲nwak̲olas Council under the Large Cultural Cedar Protocol, an operational protocol that safeguards large cultural cedars (LCC) during forestry activity. The protocol is initially implemented at the cutblock planning phase.

“When a licensee locates potential LCC trees within the proposed cutblock, these trees are tagged and mapped by the licensee, and then this information is shared with the Nanwakolas member Nations through a referrals process,” says Dr. Julie Nielsen, Na̲nwak̲olas Forest Stewardship Advisor. “The member Nations, whose territory the cutblock is on, have their Guardian crews survey the proposed cutblock for LCCs, ensuring the licensee’s information is correct.”

Guardians record details about each LCC and its surrounding site, which is then catalogued in Na̲nwak̲olas’ LCC Inventory. Using this information, the Nations decide which LCC trees will be marked for Nations’ use and which will be marked for the licensee.

“The Nations may choose to retain all their LCCs in the cutblock, not harvesting them, or get the licensee to harvest one or more LCCs to meet their current cultural needs,” says Julie. “Most often, Nations choose to retain their portion of LCCs in the cutblocks, leaving them standing for the next generation.”

Na̲nwak̲olas Council’s LCC protocol is one of many ways the Council supports the needs of member Nations. Established in 2007, the Na̲nwak̲olas Council includes Nations from the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw group of Nations whose territories cover about a third of Vancouver Island – from Englishman River to Kokish River – along with adjacent ocean and islands, and up into the mainland coast from Bute Inlet to Knight Inlet.

In Kwak’wala, Na̲nwak̲olas means “a place we go to find agreement.” The member First Nations make their own decisions about resource development and stewardship within their territories, and come together to share technical expertise, coordinate their efforts, and advocate as a group.

Today, the Na̲nwak̲olas Council provides a range of services for First Nations, including support with development referrals, marine planning, mapping, forestry, and stewardship training. In matters that concern all member Nations, Na̲nwak̲olas can advocate for members’ Aboriginal Rights and collective interests. Importantly, First Nations can choose whether and how they would like to work with the Council, which services they’d like to receive, and whether to engage in larger agreements facilitated through the Council.

LCCs, are old-growth trees which, according to the BC Ministry of Forests, are more than 250 years old, have been greatly impacted by excessive resource extraction dating back to European settlers’ arrival, making them increasingly hard to source for First Nations’ cultural use.

In addition to their cultural, spiritual and economic values, LCCs hold significant ecological value, says Julie.

“LCCs are a non-renewable resource that is profoundly different from second-growth red cedar,” she says, noting that second-growth trees develop in open-growing conditions which does not promote the traits of old-growth trees, such as tight growth rings and few branch knots, which are desirable for carving.

“LCCs and other old-growth forms of red cedar contribute to the structure and function of old-growth forests by supporting soil development and slope stability, serving as seed sources and ‘mother trees,’ substantially influencing stand structural diversity, and providing habitat for a plethora of plant and animal species, including calicioid lichen species endemic to red cedar,” Julie explains.

“Once an old-growth forest stand is harvested, it is gone and never coming back,” says Julie. “Often, a second-growth stand will replace it, which will never develop the characteristics of the old-growth stands we see today, at least not in several of our lifetimes, and likely never.”

Economic Reconciliation Through Forestry Stewardship

In August, Na̲nwak̲olas hosted a log blessing ceremony in the log sort of La-kwa sa muqw Forestry (LKSM) at Kelsey Bay Wharf by the Sayward River estuary. Backdropped by the luscious greenery of the H’kusam and Tsitika mountains, the ceremony brought member First Nations and industry partners together to celebrate forestry stewardship and First Nations’ vital connection to their lands and forests.

“This area has been an important place, culturally, for our people for thousands of years,” said Dallas Smith, member of the Tlowitsis Nation, President of Na̲nwak̲olas Council, and board Chair of Coast Funds.

Eight recently harvested LCCs were positioned behind the speakers. Standing side by side, Dallas Smith, Chief Councillor Roberts (Wei Wai Kum), Chief Councillor Chickite (We Wai Kai), Chief Councillor Rempel (K’ómoks), and Steve Hofer (President and CEO, Western Forest Products) shared speeches with guests.

“Reconciliation isn’t about taking anything away, it’s about putting more into it,” said Dallas. “We need an economy. We need that balance of ecological protection, but we also need that human well-being.”

We’re up to the challenge. We continue to work with each other, and we need to have these relationships.

On the Great Bear Coast, First Nations have demonstrated that, for conservation efforts to have lasting success, governments and partners must also invest in local communities and economies, creating opportunities for Indigenous people to thrive in their homelands.

“We wanted to set ourselves up as a self-sufficient Nation,” said Chief Councillor Chickite. “I think being that type of leader, showing other First Nations as well, that, if you make some investments, you can become leaders in that industry. I think La-kwa sa muqw Forestry is a prime example.”

Established in April 2024, LKSM brings Tlowitsis, We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, K’ómoks, and Western Forest Products together through a $35.9 million limited partnership that covers approximately 157,000 hectares of forest. Through the agreement, Nations acquired a 34 per cent interest in Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 64 and an allowable annual cut of more than 900,000 cubic metres of timber.

The agreement, which is intended as a collaborative process, supports participating Nations and industry partners to work together, creating a balance in resource management and First Nations’ community well-being.

“We’re up to the challenge. We continue to work with each other, and we need to have these relationships,” said Chief Councillor Roberts. “We need to acknowledge our differences, because there is always more that unites us than sets us apart…We have many challenges as the people of this planet, and the people of this territory [are finding] a balance between resource extraction, forestry, and education.”

Together, Tlowitsis, We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, and K’ómoks First Nations are working to participate meaningfully in forestry stewardship. In addition to upholding Na̲nwak̲olas’ LCC Protocol, the Nations’ Guardians are trained to identify Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs), a value honoured in the TFL 64 agreement. CMTs are living trees that have been altered by Indigenous people, usually by stripping, planking, or carving. These trees, carefully modified by First Nations often hundreds of years ago, bear marks that demonstrate First Nations’ long-term occupancy and use of their territories. First Nations take care to ensure the scars left on these trees are minimal. The tree can heal, grow, and continue its life without harm, illustrating First Nations’ sustainable harvesting techniques.

“The culturally modified trees, the archeological artifacts that have been found just in the 50 square kilometers around this area, are just awesome. It’s inspiring,” says Dallas.

Carving in H’kusam Forest

First Nations’ history of sustainable forestry management and cultural practices in British Columbia, like bark collection and living tree carvings, dates back thousands of years. Today, these practices are being continued by carvers like Max Chickite, Junior Henderson, and Karver Everson.

High in the mountain tops of H’kusam forest, Max walks through a clearing surrounded by thistles and red huckleberry. He is standing in the carvers’ camp, deep in the old-growth forest. Behind Max, with a stunning view of Sayward’s Salmon River Estuary, is a small cabin holding space for eight beds, some shelving, and a hammock. At this camp, Max, Junior, and Karver mentored four apprentice carvers, Brent Smith, Jalen Henderson Price, James Kwaksistala, and Raymond Shaw. Together, they worked on several projects over 30 days at the camp, including the canoe, G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala.

“Thirty days in the forest is a long time,” said Junior Henderson at the log blessing ceremony in Sayward. “You start to realize what our people were like, how they must have acted, and how they felt the energy that’s out there. The only way you’ll know is to do it yourself.”

The carvers fasted and built a creek-side sweat lodge downhill from the camp.

“Me, James, and Brent put the sweat lodge together. They took command from me, mostly,” Max shares while walking through the forest. “But everybody’s in it together.”

I continuously thought about the old people. What would they have done?

Traditionally, fasting and using sweat lodges has been an important part of cleansing and healing for First Nations in many parts of North America.

“For [the carvers] to commit to the fasting process, it’s a scary thing to think that you’re not going to eat for four days,” said Junior. “You’re [also] going to bathe every morning, at daybreak, and finish cleaning up and doing the work that still needs to be done – with little energy.”

Na̲nwak̲olas staff set up remote trail cameras to document the hours of work the carvers put into the initial digging and chopping stages to prepare G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala for carving. (A year ago, Max, Junior, and Karver worked at the same site to dig out and prepare Na̱max̱sa̱la, the first xwax’wa̱na canoe carved in recent years.).

“I was really impressed about how we moved [the windfall cedar] from one area to another,” recalls Max. “We worked together and we had no hydraulics, nothing there to help. We just had chain pulls and blocks of wood.”

The carvers worked methodically in the forest, cutting the windfall cedar to size. It took two days for the carvers to move the cedar, by hand, from where it had originally fallen less than 100 metres away from the carving site.

“I continuously thought about the old people. What would they have done?” Junior shared in a video reflecting on his time carving Na̱max̱sa̱la. “Back in the old day, there would have been 12 or 15 of them, all helping each other clear the land, clearing the area, and setting things up.”

“When we moved the canoe, we landed on the carving deck, where we carved [Na̱max̱sa̱la], on Aboriginal Day,” says Max back at the camp. “It just happened to be that day.”

Max walks deeper into the old growth. The further away he gets from camp, the denser the forest floor feels underfoot, layered with decomposing leaves that have been compressed over time. The biodiversity in the forest is vast with towering conifers like Douglas and Pacific silver firs, Western hemlocks, and yellow cedars that form a canopy shielding the forest’s understory – lush with sword ferns, salal, and false azalea – from harsh weather conditions.

Throughout the forest, Max points out western red and yellow LCCs and marked CMTs. Some trees have been planked or stripped; others are huge windfall cedars. Some of these trees were harvested from over 400 years ago.

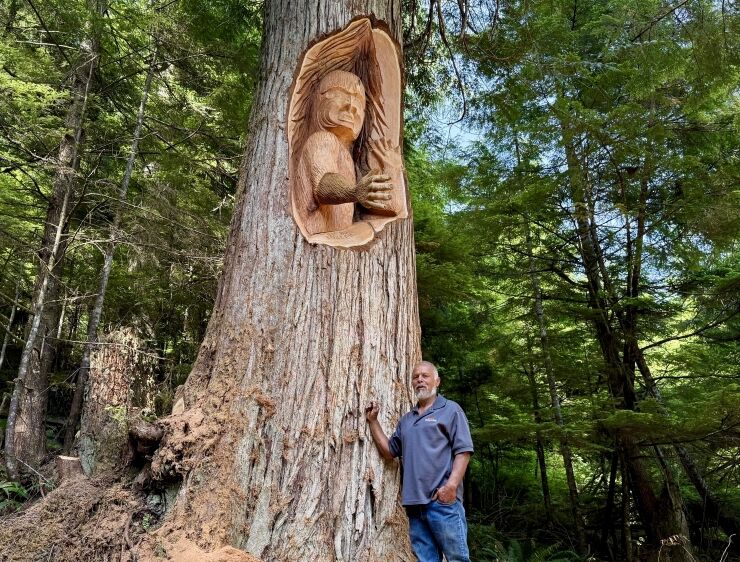

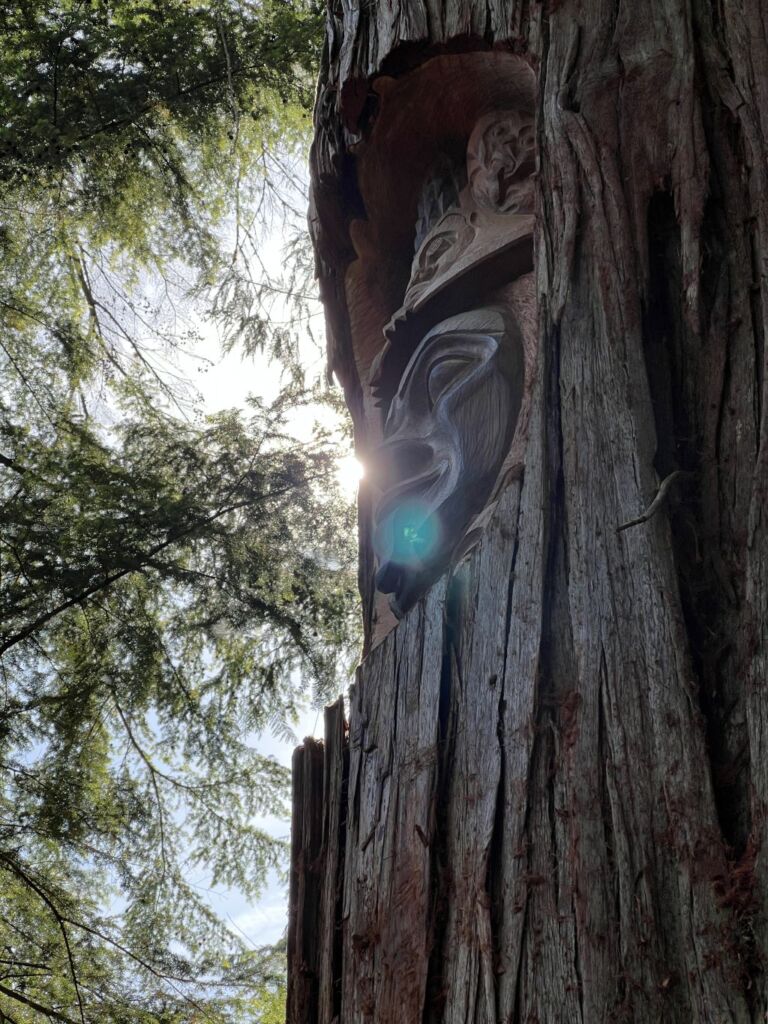

Max stops in his tracks and smiles with his hand stretched out in the direction of a small break in the forest. Standing before him are three figures that have been carved into the centre of three LCCs, each standing almost 45 metres tall.

Referred to as living carvings, each tree has been carved to represent three different figures of significance to the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw people. The first is a female figure, designed by Junior Henderson, and carved by Junior and Raymond. Watching over her shoulder is a male figure, designed by Karver Everson, and carved by Karver, Jalen, and James. Together, these two figures represent the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw peoples.

The third figure, carved by Max and Brent, represents Bakwus the wild man who appears to be fleeing from the two human figures. The wild man’s right arm is outstretched for protection as he turns to run away and retreat into the forest.

The carvings are almost two metres tall and span about a third of the tree’s width. Evidence of living carvings, like these, are found throughout the Great Bear Rainforest and were carved by First Nations for hundreds of years.

CMTs, like living carvings, would be created for many reasons: to share information, like directions, with other community members; or to harvest parts for canoes, poles, clothing, or tools.

These living carvings convey the message that First Nations people have always been here and are continuing to monitor and use their traditional territories, applying Traditional Knowledge and cultural practices passed down for generations.

“Without this project, we wouldn’t have been able to create those opportunities to train young carvers,” said Junior Henderson back at the log blessing ceremony. “I think we all picked the right people to bring into this project, to be able to pass on that knowledge.”

Carving a Legacy

After the log blessing ceremony, lead carvers Max, Junior, and Karver introduced G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala to their family, supporters, and wider communities. As they launched the xwax’wa̱na canoe into the calm waters of Kelsey Bay, guests could see that G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala had been sealed and painted with formline of a wolf and a killer whale designed by Max’s daughter, Jessica Chickite, and painted with help from all seven carvers.

G̱a̱lg̱a̱połala, which fittingly means to ‘hold each other up’ or ‘holding hands’ in Kwak̓wala, is a celebration of months of hard work and the enduring cultural traditions carvers like Max, Junior, and Karver are revitalizing in their communities.

“It was incredible to work with [Junior and Karver]. The carvers respecting each other, taking each others knowledge, and making it happen,” said Max in a video, documenting the historic making of Na̱max̱sa̱la.

“We gave so much of ourselves to be there and developed a strong relationship,” added Karver. “You can’t do a project like that without strong relationships.”

Na̱max̱sa̱la marked the first time that a xwax’wa̱na had been carved using traditional methods in over a hundred years in Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw territories.

“We did the best we could with the spiritual connection that we have, to one another, to our culture, to the way that we live our life,” said Junior.

Back at Quinsam Reserve, reflecting on his years of work and passion for carving, Max looks fondly over at a recently completed project: a “little Big House” in the playground of We Wai Kai’s λugʷ e las Childcare and Education Centre that’s made of red cedar poles that incorporate an eagle, owl, orca, and a bear eating salmon.

Many of Max’s works can be spotted around Quinsam Reserve; at its entrance, three welcome figures stand side by side, showcasing We Wai Kai hospitality: two with arms open in welcome, one with a full belly. They are ready to share food, stories, and connection.

For carvers like Max, Junior, and Karver, they are able to earn a living from their practice by balancing carving for ceremony and culture. It is their hope that traditional practices, like carving a xwax’wa̱na, can be passed down for generations, continuing the story of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw and Liǧʷiłdax̌ʷ peoples.

“We all kind of put our heads together and made it a group talk, you know?” Max says. “Back in the day, our people used to have racing canoes that would fit 10-11 people. When I was young, I paddled one, we used to have that in the village, back in the day. So that’s what we are going to do [next] – the [apprentice carvers] are up for any project we can come up with.”

New carving projects keep arriving at Max’s doorstep, but he isn’t worried about creative burnout.

“Not at all. It’s kind of a pleasure, partly like therapy, and it’s peaceful,” he says. “Every time I learn about my culture, I am inspired.”

Using their investments with the Coast Conservation Endowment Fund Foundation, Na̲nwak̲olas member First Nations operate Guardian and monitoring programs and contribute to the Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network.

Partnerships

Links

- Politics of the Canoe,

Bruce Erickson and Sarah Wylie Krotz - Ha-ma-yas Stewardship Network

Na̲nwak̲olas Council - Estimating the amount of British Columbia’s “big-treed” old growth: Navigating messy indicators

Karen Price, Dave Daust, Kiri Daust, and Rachel Holt - Large Cultural Cedar Protocol Declaration

Na̲nwak̲olas Council - Episode 6: Chickite Family Art

Treaty Talk Podcast

Published On December 18, 2025 | Edited On January 21, 2026