Spirit Bear Lodge, owned and operated by Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation, has become a successful model for conservation-based ecotourism. The Lodge has helped strengthen economic, conservation, and cultural well-being in the community of Klemtu.

The Success of Spirit Bear Lodge: How a Remote, Community-led Business Became a Global Model for Ecotourism

Estimated Reading time

48 Mins

Wee’get, the Raven, being the creator and wishing to leave a reminder for all time that once the land was white with ice and snow, set an island aside to be the home of the White Bear People. Then he went among the black bears and every tenth one he made white, and decreed that they would never leave the island for here they could live in peace forever.

– Story of the Hás!xλiλ︠á (Spirit Bear) told in “Somewhere Between” by Anthony Carter who collected the stories and history of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais.

Spirit Bear Lodge is located on Swindle Island in Finlayson Channel, approximately 219 kilometres north of Vancouver Island in the coastal fjords of British Columbia, Canada.

At A Glance

For many years, Kitasoo/Xai’xais elders rarely spoke of the Spirit Bear for fear it would be hunted into extinction if word spread of its existence. Yet today, the bear is globally recognized and just the opposite has happened: tourists travel from across the globe for a chance to glimpse the animal.

The celebrity of the creature parallels, and is in large part due to, the success of the eponymous Spirit Bear Lodge. Like the bear whose image adorns its logo, the lodge has become known worldwide. Over the last two decades, Spirit Bear Lodge has helped strengthen economic, conservation, and cultural well-being in the community of Klemtu at the heart of Kitasoo/Xai’xais territory.

Employing nearly 10 per cent of the local population, the Lodge has diversified opportunities for employment in the community, particularly for youth. Additionally, drawing attention to the region’s stunning landscape and globally rare species like the Spirit Bear, the business helped attract researchers to the area and strengthen protection of the Nation’s vast territory. And perhaps most importantly, it played a major role in the establishment of a cultural stewardship program for the Nation’s youth and elders.

The story of Spirit Bear Lodge is about more than just a successful ecotourism business, it is the story of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation creating a conservation-focused, one-of-a-kind, sustainable business in one of the most remote places in Canada.

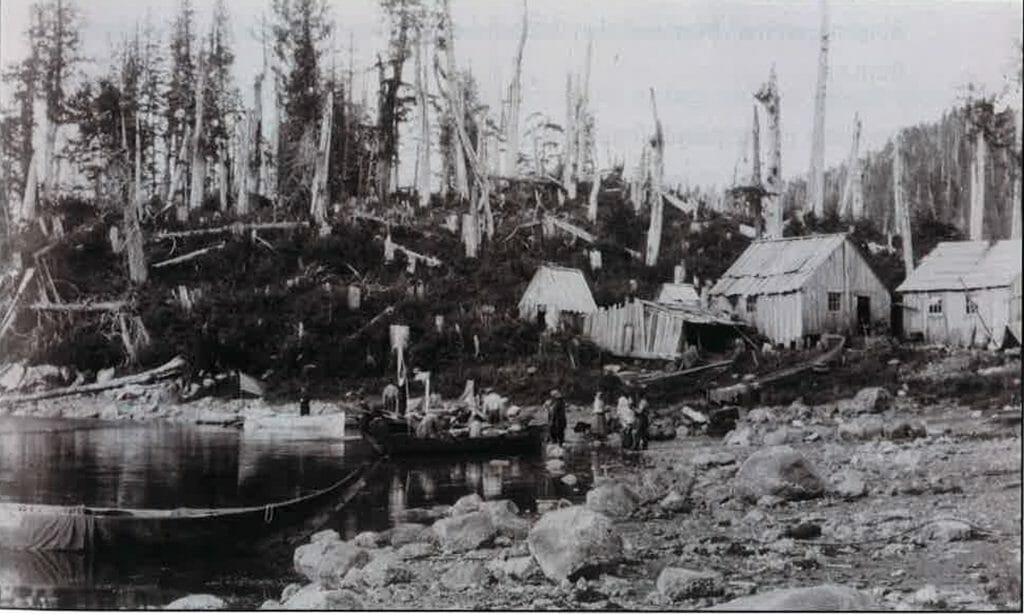

From Colonial Extractive Economies to Sustainable Ecotourism

The Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation is an amalgamation of two distinct tribes. The Kitasoo, from the outer islands are part of the Tsimshian language family, and the Xai’xais, from the mainland inlets, are part of the Wakashan language family. The two groups began to settle in Klemtu (Klemdulxk), on Swindle Island around 1875 to take advantage of its strategic location on the inside passage for trade and the supply of cordwood to steamships travelling the coast. Sometime around the 1830s the Kitasoo and Xai’xais tribes were significantly impacted by exposure new viruses transferred from colonialists with some villages suffering large population losses. Finally, when the Canadian government established the reserve system and moved what remained of “Indians” from the territory to Klemtu the two distinct groups formed one Nation.

The natural ecosystems in the region also suffered from colonialism. For well over 100 years, resources such as fish, and to a lesser extent forests, were unsustainably extracted with no compensation provided to the Kitasoo/Xai’xais people. Klemtu, like other First Nation communities along the coast, suffered extensive economic, social and cultural damage throughout this period.

In the 1980s and 1990s the Kitasoo/Xai’xais began to develop a community-based economy. By using revenue from a commercial herring spawn on kelp license, and securing additional community-owned licenses such as sea cucumber, urchin, prawn and others, the community was able to build a seafood processing plant. Soon after they began farming salmon which provided significant new revenues and jobs. Further inroads were made by asserting management over forestry harvesting in the territory which eventually led to acquisition of forest tenures and additional revenues.

Our vision for our land and resources is based on the best definition of the term ‘sustainable’. To us this means that the wealth of forests, fish, wildlife and the complexity of all life will be here forever.

In their Land Use Plan produced in 1999 and 2000, the Nation identified ecotourism (non-extractive tourism) as a new economic opportunity developing from the new protection of areas in their territory. Doug Neasloss, Resource Stewardship Director, former Chief Councillor for the Nation, and a former long-time employee of Spirit Bear Lodge, recalls the early conversations around bringing tourism to their community. “It was a concept that was very new. The elders were concerned about people looking in our windows, or that visitors would buy up local supplies and fuel,” he remembers.

Despite initial concerns, the community began to see the potential of ecotourism to bring economic, cultural and environmental benefits to their territory. Larry Greba, who has been a director of the Kitasoo Development Corporation since its establishment in 1994, says the community was able to see parallels between ecotourism and their own conservation-based approach to resource management.

Unlike the colonial, extractive industries that had operated in the region for decades, ecotourism was an industry that would use the natural resources of the territory in accordance with cultural laws, knowledge and values. Their traditional resource plan was guided by oral history and their rich cultural tradition and knowledge. The people, the land, and the sea care for and sustained one another.

“Our vision for our land and resources is based on the best definition of the term ‘sustainable’,” says Neasloss. “To us this means that the wealth of forests, fish, wildlife and the complexity of all life will be here forever. It also means that we will be here forever. To remain here as Kitasoo and Xai’xais people, we need to protect and enhance our culture and protect our heritage.”

Neasloss suggests that the ecotourism activities at Spirit Bear Lodge are aligned with Kitasoo/Xai’xais cultural values. “The elders always say what we have is not ours, we’re just holding it for the next generation. That’s really important in whatever we do that we look at the model and say we’re going to take care of it and make sure the next generation has something.” Neasloss also saw in ecotourism an opportunity to provide an alternate source of employment especially for women and youth in the community.

And so, from a downturn in extractive economies like fishing and a desire to reassert control and ownership of their traditional territory, the business that would eventually become Spirit Bear Lodge was formed.

A Direct Tie-In to Conservation of the Great Bear Rainforest and Sea

During the campaigns that led to the Great Bear Rainforest agreements, the area around Klemtu was becoming a hub of activity. Former manager of Spirit Bear Lodge, Evan Loveless, notes that “the campaigns were ramping up and environmental groups were profiling the Spirit Bear as a key campaign symbol.” For the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation, who were actively involved in negotiating the agreements, it was a natural extension to capitalize on the activity and promotion taking place, and establish a tourism business in Klemtu.

We went from a community largely dependent on resource extractive jobs to a community whose economy was largely based on conservation and non-extractive activities.

The Great Bear Rainforest agreements were a turning point for economic development in Klemtu notes Doug Neasloss. Under the agreements 50 per cent of Kitasoo/Xai’xais territory is now protected from logging, mining and other resource extraction, but can be used by members for food gathering and traditional uses, and for ecotourism. The remaining is managed according to ecosystem-based management principles and actions.

“The new protected areas helped this community turn 180 degrees,” Neasloss says. “We went from a community largely dependent on resource extractive jobs to a community whose economy was largely based on conservation and non-extractive activities.” He credits much of the success to the development of ecotourism in the region and to the development of Spirit Bear Lodge. Funding raised as part of the agreements along with hard-earned profits from the Kitasoo Development Corporation have been strategically invested by Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation to develop Spirit Bear Lodge into the success it is today.

Community members pushed for Spirit Bear Lodge to be more than just a business and so it was. As the lodge grew it helped the Nation play a much bigger role in stewardship and management of their territory. The Lodge contributes to conservation in the area by helping to protect visual corridors, educating visitors, and working with researchers in the Fiordland and Spirit Bear Conservancies and elsewhere in the territory.

The Lodge was recognized as an important tool for helping to protect the traditional territory of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais, as a catalyst for cultural renewal, and as a means to re-connect community members with their ancestral territory. Former manager Tim McGrady remembers the strength of the vision held by Neasloss, Greba, and Hereditary Chief (and Lodge employee) Charlie Mason. “Those three people really held the dream, the vision. They knew where they wanted to be.”

From Walking Tours to Kayak Trips

Klemtu Tourism, as the Lodge’s precursor was originally called, was launched in 1996 coinciding with the arrival of the first BC Ferry. Between 1996 and 2000, Klemtu Tourism offered an interpretive walking tour for passengers during the ferry’s three-hour stop at the local terminal. Guests were provided with a local buffet featuring traditional foods and a dance performance.

Cindy Robinson, one of the original walking tour guides remembers a desire to change biases toward Indigenous people and keep the culture of their community alive. “Tourism provided an opportunity to show pride in who we are,” says Robinson. Being given a platform to learn and talk about the Nation’s culture and history gave her a sense of self-esteem and confidence. “We wore forest green shirts that said ‘Klemtu Tourism,’” she laughs. “We felt kind of sophisticated.”

Over time the business recognized a need to diversify their market beyond ferry passenger traffic. During a thorough tourism opportunities study completed in 1999 (in partnership with Thompson Rivers University) consultation with the local community revealed a desire to focus on non-consumptive tourism and to promote Klemtu as a destination, Klemtu Tourism decided to turn its focus to a growing segment of the tourism sector: ecotourism.

Tourism provided an opportunity to show pride in who we are.

In 2000, Evan Loveless was hired as General Manager to run the ecotourism business at the recommendation of his professor who had worked on the community consultation. Loveless trained a skeleton crew from the walking tours to act as guides. An existing floathouse was used as guest accommodation. The guides took tourists on multi-day trips oriented around bear and whale-watching, and visiting cultural sites. They also offered kayaking tours using newly built eco-cabins and kayak campsites near local estuaries.

Of course, as Loveless notes, bears were the hook. In particular, the Spirit Bear. “We started doing bear tours right from the get-go,” Loveless says. “That was identified as one of the key opportunities for us.”

Neasloss, who began working with Loveless soon after, recognized the importance of the bears and bear viewing to creating the ecotourism industry. “Bears are very important to be able to create the industry here. It’s very important for us that we can show ways of employment that are long-term and sustainable.”

As wildlife viewing, in particular bear viewing, was gaining more and more popularity and capturing a larger market share of BC’s tourism industry, the business further focused on boat tours for wildlife viewing and visiting cultural sites. Additional chartered vessels and professional operators were added to the tourism program.

Bears are very important to be able to create the industry here. It’s very important for us that we can show ways of employment that are long-term and sustainable.

Shortly after, Loveless encouraged the Kitasoo Development Corporation to transition from the floathouse accommodation to a six-room ecotourism lodge. Funds obtained from the Kitasoo Development Corporation were supplemented with funds from the Coast Sustainability Trust to design and build what would eventually become Spirit Bear Lodge.

The Turning Points to Success

Several major turning points for the business occurred between 2009 and 2015, all of which played an integral role in the business’s success.

In 2009, Tim McGrady was hired as general manager to run Spirit Bear Adventures, as Klemtu Tourism had now become known. McGrady was excited by the opportunity to collaborate with the community on their business. “It was a real coming together of a number of strands in my life. I loved bears, I loved adventure, and I loved remote places. I just jumped in with both feet.”

McGrady’s extensive experience in the tourism and marketing industry was seen as a huge asset, but initially his ideas met with some resistance. Neasloss recalls that on his very first day McGrady wanted to change the name of the business to Spirit Bear Lodge. He says there was some reluctance to the idea, but McGrady insisted the name change would help the Lodge cater to the right market.

Larry Greba also recalls that McGrady’s expectations for growth seemed overly optimistic. He suggested the Lodge build six more rooms (already planned within the initial 2006 lodge design) and a commercial kitchen, more than doubling its size. Eventually Greba was convinced that the expansion would allow the business to become profitable and funds were secured from the Kitasoo Development Corporation and Coast Funds. The expansion took place in 2011.

The financing from Coast Funds came from the Great Bear Rainforest agreements and was designated to develop sustainable economic development and conservation projects in the region. “Coast Funds supported the expansion of the lodge,” says Greba, who also sits on the Board of Coast Funds. “That was fairly important and integral to taking us over the top to being successful. It made it much easier in the community to make a decision around the expansion and to make the much needed improvements to make the lodge world class.”

Architecturally designed, the exterior of the Lodge pays homage to the traditional long houses built for thousands of years by west coast First Nations, with 20-foot high, ocean view windows and local Tsimshian art. The art adorning the walls of the great room is a reproduction of the front-face of a Kitasoo ancestral big house.

Success Inspired by the Spirit Bear

As the lodge was being expanded, Rolf Skala, a branding specialist, was hired by Greba to come up with a new look, new logo and a new website to go along with a change in name from Spirit Bear Adventures to Spirit Bear Lodge. This was a critical decision to turn the market positioning away from an adventure tour operation to a high quality cultural lodge with day trips to experience bears, including the rare Spirit Bear.

The Kitasoo Band Council had officially registered the Spirit Bear as a trademark in 2006, and the Lodge adopted the animal into its logo. McGrady convinced Greba to secure the domain name spiritbear.com, which was owned at the time by a bike tour company in Oregon, a move which helped propel the Lodge to the top of online searches.

Skala says that the Spirit Bear brand works as an inspirational catalyst to honour, value and assist in the reawakening of the unique Kitasoo/Xai’xais identity and culture. Hereditary Chief Charlie Mason talks often of the significance of the Spirit Bear to Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture. Perhaps most memorably he tells of how a Spirit Bear came to Klemtu on the day the community opened their new big house.

The new big house is replica of Dis’ju—an ancient big house in Laredo Channel which some tourists are able to visit during their stay with Spirit Bear Lodge. Mason’s mother was instrumental in its construction. “She passed on before the big house was completed,” says Mason. But during the celebration for its opening a Spirit Bear swam from Cone Island across to Klemtu. “As the Hás!xλiλ︠á (Spirit Bear) came ashore, it went from one side of the big house to the other two times before it went off. The White Bear was my mother who came to look at the big house and give her blessing to the building.”

Following re-branding the business began to be referred to affectionately by locals as ‘the Lodge’, giving the business strong positioning and identity within the community. “It was exciting to see that happen,” McGrady says. “It was exciting to see how different things we did in the Lodge and in the community really helped build that social license that Doug [Neasloss] was working toward in the community.”

Profitability was never a driving force, it was more important to provide meaningful jobs in the community and provide opportunities for youth to get involved in the workforce.

Outside the community, the rebranding was also proving to be a success. The Lodge began to receive international attention and business began to double in size each year for the next few years, reaching the critical threshold for profitability in 2014.

Greba says the Lodge came further than anyone thought it could. “The money just came with the success of the true roots of what we wanted to do,” he says. “Profitability was never a driving force, it was more important to provide meaningful jobs in the community and provide opportunities for youth to get involved in the workforce. If you do something you’re passionate about, you’re going to do a good job and financial success will likely follow.”

In 2011, National Geographic provided in-depth coverage of the Spirit Bear in their August 2011 issue providing huge exposure for the

coast, the iconic bear, and Spirit Bear Lodge. The Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation agreed to the article under the terms that the magazine also write an article about the threat oil pipelines and tankers posed to the region—something that National Geographic, a non-political organization, had never agreed to before in its 129-year history.

Today Spirit Bear Lodge is a showcase community tourism business in the Great Bear Rainforest, and a recognized best practice model for Indigenous community-based tourism in Canada. The business has won numerous awards including the Indigenous Adventure Award, it is listed by Canada Keep Exploring as a “Signature Experience,” and in 2017, Doug Neasloss presented on the Lodge’s business model at an environmental forum convened by the United Nations and the Centre for Responsible Travel in Washington, D.C.

Connecting to Culture

Undoubtedly, one of the most important impacts that the Lodge has had in Klemtu is to help revitalize the Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture. Tim McGrady recalls that a turning point for the lodge came when youth began showing their fascination with the Lodge and the tourists visiting their community.

“We were noticing that we were having a lot of young people sort of hanging out,” remembers Tim McGrady. “Some of the young people from the community would come in the evenings and want to learn more about what we do. So with the blessing of the elders and hereditary chiefs we started a youth cultural program.”

Together with the Kitasoo Resource Stewardship Department, Spirit Bear Lodge began sponsoring the Súa Youth Cultural Program. The word Súa is a Xai’xais word meaning thunder reflecting the youth desire to be ‘loud and proud’.

Súa performances offer an interactive experience between Kitasoo/Xai’xais youth and Spirit Bear Lodge guests. “We usually start out outside and we introduce the big house and come in and then we do a few songs and a few stories, ” says Mercedes Robinson, a member of the Súa Youth Cultural Program. She notes that the performances—sometimes in front of as many as 50 people—give her a sense of pride and self-confidence.

Though the big house is usually off-limits for outsiders, Loveless recalls that the community gave its approval for Spirit Bear Lodge to use it in hopes that it would help revive Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture.

Our aim is to encourage these young leaders to use the power of their voice to communicate their passion for their culture.

The Súa program is about more than just performance. It connects youth with their culture and history. During the summer program participants build drums, memorize traditional stories, identify and harvest native plants, weave cedar baskets and headbands, learn phrases in Sgüüx̱s (the Kitasoo dialect of Sm’algya̱x), how to fabricate traditional regalia, and most importantly, are able to visit culturally important sites in the remote areas of their territory.

“A real highlight of the program was a field trip to Dis’ju,” confirms Lisa Hackett, Program Coordinator. “The youth were granted special permission to enter the historic big house wearing their regalia to sing and drum. It was by far one of the most powerful moments of the season.”

In addition to providing opportunities for youth to explore their culture and the traditions of their people, the Súa program helps the kids to learn values such as accountability, respect, and reliability that will help them to be successful elsewhere in their lives (i.e. school and workplace). “Building self-worth in youth helps them understand the power of their individual voice. Our aim is to encourage these young leaders to use the power of their voice to communicate their passion for their culture” notes Hackett.

The youth also get an introduction to basic public speaking and performance skills helping to develop self-confidence. “I feel special because it lets other people see our culture and what we do around here. They probably haven’t seen that before,” says Robinson.

Robinson also partakes in another Kitasoo/Xai’xais cultural program called Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards (SEAS). SEAS is supported by Coast Funds, the Moore Foundation, Nature United (formerly TNC Canada), and Tides Canada. Like Súa, it aims to connect Kitasoo/Xai’xais youth with their traditional knowledge and culture.

Sprit Bear Lodge, works closely with SEAS and the Kitasoo Resource Stewardship Office to design summer internships and work experiences and with the school to support student field programs.

Working with Kitasoo/Xai’xais youth through Súa and SEAS is undoubtedly one of the most important roles Spirit Bear Lodge has in the community. “The one legacy that I think is the most powerful for [the Lodge] is the connection with the youth,” says McGrady.

Challenges and Solutions

Along the way there were many challenges to the development of the Spirit Bear Lodge business, a few of which are highlighted below so others can benefit from Kitasoo/Xai’xais learnings.

Governance – To help ensure separation of business and politics, the Kitasoo Band Council developed a trust which in turn owns the Kitasoo Development Corporation, a holding company charged with furthering the Nation’s economic development. The Kitasoo Development Corporation manages Spirit Bear Lodge LP and profits from the business flow back to the community or are reinvested in the corporation. Kitasoo Development Corporation reports to both the Band Council for matters within the community and to the Resource Stewardship Department for matters pertaining to the lands and waters within the territory.

Consistency and Direction– An important part of the success of Spirit Bear Lodge and other Kitasoo business is consistency in management direction and oversight. Ben Robinson, the current CEO of the Kitasoo Development Corporation, started working for the Band as the economic development officer in the early 1980s. Together Robinson and Greba have provided direction, oversight and key decision making for Spirit Bear Lodge as it has grown and transitioned through five general managers since 2000.

Marketing – Tourism marketing requires specialized expertise and skills particularly in today’s rapidly changing marketplace and is not typically a skill found in a community new to tourism. Spirit Bear Lodge brought in the expertise from outside Klemtu to help define and target the right audience for their unique ecotourism experience.

Staffing – Spirit Bear Lodge relied heavily on outside management expertise as their business evolved. The most critical area of expertise that helped put Spirit Bear Lodge on a sustainably profitable path was hospitality and tourism marketing (including branding) proficiency. It was also recognized that the longer-term solution to maximizing skilled staff from the community in most positions has been to ensure all outside staff recognise their goal is to find and mentor their replacement from within the community, as possible.

Hospitality – The key to differentiating this business from other bear viewing experiences available in BC has been the design of facilities and amenities and the provision of guest services and programs. The entire operation of Spirit Bear Lodge has been imbued with the Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture, from interior design and decoration in the lodge, to marketing materials, to bear viewing tours incorporating visits to sacred sites and cultural interpretation.

Patient funding support – A major challenge for many First Nations tourism enterprises is the need

for patient capital for projects to support incremental growth as the community builds tourism capacity. Fortunately, Spirit Bear Lodge was able to capitalize on support funding through the Kitasoo Development Corporation for both capital needs and occasional cash flow issues. Between 2009 and 2015 Spirit Bear Lodge accessed critical additional funding support through Coast Funds, most importantly for the capital required to right-size the lodge to 12 rooms.

Cost control – In any business that relies largely on marine transportation operating costs can quickly escalate, especially in a remote community like Klemtu. Strong cost accountability and systematizing the financial controls has also been important for Spirit Bear Lodge. The approach adopted by Kitasoo Development Corporation has been described as a ‘short arms and deep pockets’ approach. Working with an architect already engaged in the community was working for Klemtu under the strict financial discipline of the Kitasoo Development Corporation, in constructing a beautiful quality lodge that pays respect to the traditional big house.

Risk management – In 2006 a boating mishap pushed the business to place more emphasis on risk management. Spirit Bear Adventures LP was created with significant attention to risk management. Accessing outside expertise was the approach Spirit Bear Lodge adopted to assist in preparing the risk management plan and integrating risk management into guide training, and the business was incorporated as a Limited Partnership.

Success Factors for Community-based Tourism

The Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation offers the following 10 key success factors for other Indigenous communities looking to establish a similar business.

- Strategic planning is an important first step followed by business planning to ensure the business is well conceived and based on market realities.

- Build the business only as fast as the community can support. Spirit Bear Lodge underwent slow growth to allow community capacity to keep pace.

- Community-based tourism needs to be community-driven and supported with involvement on major decisions.

- Find strong management who will fully devote themselves to the business and promote a team atmosphere.

- Begin with a good mix of skilled external operational staff and community staff until the capacity is fully developed in the community.

- Find consistent champions in the community that will push the business forward no matter what the obstacle.

- Continual investment in capacity building, particularly for youth using mentorship as a key tool. In-community training is often the best approach and results in more practice for students leading to higher standards.

Moose is a Kitasoo/Xai’xais elder and a lead vessel operator for Spirit Bear Lodge. Photo by Phillip M. Charles. - Ensure availability of development, operational and capital funds when required and availability of operational support funds to bridge cash flow gaps. In the case of Spirit Bear Lodge funding available through the community Kitasoo Development Corporation was critical.

- Determine and adhere to the optimal carrying capacity. Current thought from community leadership in Klemtu is that 24 overnight guests at one time in the community and on tours of the territory is an optimal number for Spirit Bear Lodge.

- Find patience, perseverance and prepare for a lot of hard work. It took Spirit Bear Lodge 17 years to reach the business threshold and begin to turn regular profits back to the community.

Cultural Outcomes

Developing the ecotourism business has helped to stimulate a cultural re-awakening for Kitasoo/Xai’xais’ culture. Perhaps the strongest illustration of this has been the establishment of the Súa Youth Cultural Group and the integration of the Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards program.

Empowering and engaging youth in the tourism program has helped to stimulate their interest in community culture, helping to make traditional culture ‘cool’. Lisa Hackett, program coordinator for the Súa program says it helps youth to “understand the true meaning of being ambassadors of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation.” She notes that, “they hold this position with honour and pride and bring those traits into other aspects of their life at the school and in the community.”

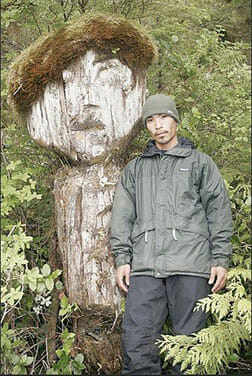

Through SEAS and the Súa Performance Group, the youth and elders of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation are reconnecting with important cultural sites in their territory, working to revitalize their, and building pride in their community.

They hold this position with honour and pride and bring those traits into other aspects of their life at the school and in the community.

The Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture is now reflected in the Lodge and the ferry terminal complex as a direct result of tourism. The big house is primarily for community cultural events and functions but has been made available for appropriate and controlled tourism purposes. Spirit Bear Lodge includes prominent artwork in the great room that reproduced from a historic longhouse.

The Spirit Bear Lodge business has provided a platform to help re-establish a connection with the territory and re-asserting Kitasoo/Xai’xais stewardship of the region. Tourism also presented the opportunity and need to protect sensitive cultural and sacred sites such as Dis’ju.

Learn more about Elders and youth outcomes.

Economic Outcomes

Perhaps most significantly, as a successful and profitable ecotourism business, Spirit Bear Lodge is a substantial contributor to cultural and economic development within Klemtu. Much of the Lodge’s profits are reinvested in language revitalization, youth development, stewardship, and further business expansions.

Larry Greba notes how important it is for the community to see the economic benefits from the lodge. “Community members recognize it as something that is theirs,” he says. “They see it as something that belongs to the community and not just to the development corporation.”

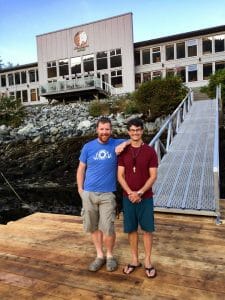

Spirit Bear Lodge has led to substantial new community investment in permanent infrastructure such as the lodge and equipment including the fleet of vessels, and the new ferry terminal facilities. In addition, Kitasoo/Xai’xais Integrated Resource Authority completed—with funding from Coast Funds—a new stewardship office in partnership with Spirit Bear Lodge. The new stewardship office, which opens in spring 2018, will serve as a residence for guides and researchers from the Lodge.

Creation of the new Spirit Bear Research Foundation in 2010/11 attracted new investment in related bear research that supports sustainability of Spirit Bear Lodge. Spirit Bear Lodge brings many travelers to Bella Bella on their way to Spirit Bear Lodge, creating potential spin-off benefits for the Heiltsuk and other First Nations.

Community members recognize [Spirit Bear Lodge] as something that is theirs. They see it as something that belongs to the community and not just to the development corporation

Spirit Bear Lodge has shown that diversification away from extractive industries is possible and beneficial. The business has created a proven model for the conservation economy that is replicable in other coastal First Nation communities. Significant new sources of revenue are generated in the community and economic leakage is minimized.

Protocols established with non-Indigenous tourism operators in the territory are resulting in better control and monitoring of tourism activity, and additional revenue to the community for conservation efforts.

Learn more about infrastructure outcomes.

Environmental Outcomes

In September 2012 Kitasoo/Xai’xais participated as a partner in declaring the ban on trophy hunting for bears in their territory due to the negative impacts sport hunting was having on the community’s growing ecotourism business. Doug Neasloss illustrates this point when he tells the story of coming across the headless carcass of a grizzly bear while guiding a group of tourists in Kitasoo/Xai’xais territory. He notes the incompatibility of the two activities and also says that because hunters make bears more skittish, tourists are less likely to see them.

McGrady suggests that work by the Spirit Bear Research Foundation (created initially through the Lodge) played a big role in establishing that ban. “I think it gave a lot of confidence to the community to push hard for the ban on the hunt,” he says. “That really spun out of the work we were doing with the lodge and that’s something I’m really proud of.”

Subsequent research by the Center for Responsible Travel in 2014 found that bear viewing in the Great Bear Rainforest generates far more value to the economy (see study), both in terms of visitor expenditures and employment opportunities than does bear hunting. The success of Spirit Bear Lodge has helped provide a basis to have this comparative analysis and support the Kitasoo/Xai’xais decision to end trophy hunting in their territory.

By operating Spirit Bear Lodge and its associated activities in the remote watersheds of the Great Bear Rainforest, the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation has been able to assert itself as an economic stakeholder within their territory. Prior to establishing this business, other tour companies would bring tourists to the region without scheduling or management of impacts on bear populations.

“Controlling tourism within the territory was an important part of the initial strategy of [Spirit Bear Lodge],” says Greba. “We had to ensure protocol agreements were in place with any outside operator.”

Research supported by Coast Funds determined how and when to allow tourists to walk in estuaries where bears feed. The research illuminated the best locations and times of day to allow these activities. The development of Spirit Bear Lodge, allowed for the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation to assert a schedule that has minimized the impact on estuaries. As a result, the sensitive areas in the regions are much better managed and there is a lower overall impact from the tourism industry.

Controlling tourism within the territory was an important part of the initial strategy of [Spirit Bear Lodge]. We had to ensure protocol agreements were in place with any outside operator.

Spirit Bear Lodge works closely with the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Guardian Watchmen program. The Watchmen help to monitor other tourism use in the territory and they utilize the cabins built for the tourism program. They also act as resource persons for the tourism programs often presenting on their research to the lodge guests in the evenings.

Researchers from the Spirit Bear Research Foundation often give talks to visitors at the Spirit Bear Lodge. The Foundation is a collaboration between the First Nation and conservation scientists. Research conducted by the Foundation has focused on the movement of grizzly populations to local islands, estimating the population numbers in the area including the number of black bears carrying the white recessive gene (Spirit Bears).

Lodge guests are recognized as potential donors to the Foundation and at the very least as ambassadors for the research work conducted by the Watchmen and Foundation scientists.

Spirit Bear Lodge will be a key tenant in the new community Resource Stewardship office building which will open in 2018, further illustrating the close relationship between tourism and the community role in conserving the territory.

Through the Nation’s land management plan a full 50 per cent of the territory has permanent protection status. Tourism has helped protect key visual corridors throughout the territory in addition, something that was not provided for the in the ecosystem-based management of the remainder 50 per cent. The Lodge has also helped raise the profile of the conservation economy developed with the Kitasoo/Xai’xais leadership.

Learn more about research outcomes.

Social Outcomes

One of the initial objectives of ecotourism in Klemtu was to create local employment. Spirit Bea

r Lodge creates significant local employment and business opportunities and spill over for existing businesses like the gas dock and store. 25 Spirit Bear Lodge employees are from the community, employing nearly 10 per cent of the population. Employees from outside the community recognize they have to train their eventual replacement from within the community.

Resource Stewardship Director Doug Neasloss notes how important the jobs created through the Lodge are to the community. The Lodge provides a new and diverse source of employment in Klemtu, separate from the traditional industries of logging and fishing. In addition, whereas those traditional industries tend to be more male-dominated, jobs at Spirit Bear Lodge and within ecotourism may be more inviting to women and youth in the community.

“It provides another source of jobs in the community,” says Larry Greba. “In particular for the youth in the community. It’s often an entry point for young people, especially ones that don’t want to work in other industries, it gives them an alternative.”

Larry Greba points to the importance of bringing in outside expertise to benefit the people of Klemtu when undertaking something new like this business. “That’s how people learn,” he says. “There’s other skills that are brought in and there’s a sharing that happens. There’s a sharing of Kitasoo culture and there’s other skills that are brought in from the outside. That’s critical in terms of capacity building.”

Spirit Bear Lodge has helped to put Klemtu ‘on the map’ in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest providing significant profile and exposure both domestically and internationally. In 1996 there were few community members who owned boats and many were becoming disconnected from their ancestral territory and the Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture and traditions. The tourism business has made a concerted effort to reconnect band members with their ancestral territory, and perhaps most importantly to introduce community youth to their ancestral lands and customs/traditions.

It provides another source of jobs in the community, in particular for the youth in the community. It’s often an entry point for young people, especially ones that don’t want to work in other industries, it gives them an alternative.

Ecotourism is well aligned with the lifestyles and values of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais people. Guides are proud to be themselves when they are out on the land with guests. Hosting international guests with a sincere interest and respect for their First Nation culture and lands has stimulated increased pride in culture and place for many community members.

“There’s a lot of transferable skills in ecotourism,” says Neasloss. “It’s not just about viewing bears. You learn communication skills, you learn how to work with wildlife, there’s the science work that we do. It’s a lot broader and this means a lot for the community.” Many of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais key Resource Stewardship staff worked previously as guides for Spirit Bear Lodge. Spending significant time in the territory guiding groups and visiting important cultural locations and sites gives staff a good sense for the state of resources in the territory and how they should be managed.

The wide range of specialised training provided to Spirit Bear Lodge employees such as small vessel operator proficiency (SVOP), marine emergency duties (MED), wilderness first aid, First Host, cultural tourism, culinary, and hospitality have equipped many community members with valuable skills that are transferable beyond tourism.

Learn more about training outcomes.

Between 2009 and 2015, Coast Economic Development Society approved funding for three projects totalling $1,099,000 toward Kitasoo/Xai’xais development of Spirit Bear Lodge.

Partnerships

- Súa Youth Performance Group

- Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards

- Spirit Bear Research Foundation

- Aboriginal Tourism BC

- Centre for Responsible Travel

- Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada

- University of Victoria

- Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance

- Central Coast Bear Working Group

- BC Parks

- North King Lodge

- Blue Water Adventures

- Maple Leaf Adventures

- Ocean Light II Adventures

- Ocean Adventures

- Mothership Adventures

Online Resources

- Spirit Bear Lodge

Website for Spirit Bear Lodge - Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation

Website for the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation - Spirit Bear Research Foundation

Website for Spirit Bear Research Foundation - Great Bear Rainforest

Learn about the Great Bear Rainforest agreements - Fiordland Conservancy

Fiordland Conservancy is located in the traditional territory of the Kitasoo / Xai’xais Nation. - Kitasoo Spirit Bear Conservancy

Kitasoo Spirit Bear Conservancy is located in the traditional territory of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation. - Kitasoo/Xai'xais Guardian Watchmen

Coastal First Nations Guardian Watchmen - Kitasoo/Xai'xais - Sua Cultural Group

Sua Cultural Group - Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards

Website for Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards - Center for Responsible Travel

Website for Center for Responsible Travel - Coast Sustainability Trust

Website for Coast Sustainability Trust - First Nations Fight to Protect the Rare Spirit Bear from Hunters

National Geographic, October 2017 - Kermode Bear

National Geographic, 2011 - It’s a lucky break to catch a glimpse of the revered spirit bear in B.C.

Toronto Star, November 2017 - This Rare, White Bear May Be the Key to Saving a Canadian Rainforest

Smithsonian Magazine, September 2015 - Keepers of Great Bear

The Nature Conservancy, Spring 2017 - Economic Impact of Bear Viewing and Bear Hunting in The Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia

Centre for Responsible Travel, January 2014 - How to Save a Rainforest

Biographic, December 2017

Published On March 9, 2018 | Edited On February 12, 2026