After Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims (Nass River) oolichan were assessed as a species of special concern, the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government undertook a multi-year research project that would protect their connection to the culturally important fish.

The Saviour Fish: Protecting Nisga’a Connection to Oolichan

Estimated Reading time

29 Mins

The Nisga’a territory covers 200,000 hectares and reaches from the mouth of the Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims (the Nass River) to the Hazelton Mountains. The main communities are located in the Nass Valley and in the villages of Ging̲olx, Lax̱g̱alts’ap, , Gitwinksihlkw and Gitlax̱t’aamiks.

At a Glance

For thousands of years, the Nisg̱a’a people have harvested oolichan from Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims, the Nass River. It is their saviour fish, its arrival signaling winter is over and the season of harvest has begun.

The devastating collapse of oolichan stocks across the coast of British Columbia has impacted First Nations’ culture and access to traditional foods. In 2011, when the Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims oolichan was assessed as “threatened” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), the Nisg̱a’a Nation worried its connection to oolichan might also be in danger.

In 2013, after pushing for a re-assessment of oolichan as a “Species of Special Concern,” the Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department undertook a multi-year research project that would provide concrete evidence of the fish’s population, support its efforts at conserving the oolichan population, and ensure Nisga’a citizens can continue to harvest the fish each year.

A Fish Central to Nisga’a Culture

The oolichan is a fish of many names: eulachon, ooligan, hooligan. It is sometimes called candlefish because it is so high in oil content that when dried it can be fitted with a wick and used as a candle. To scientists it is Thaleichthys pacificus. To the Nisga’a it is saak, or the saviour fish.

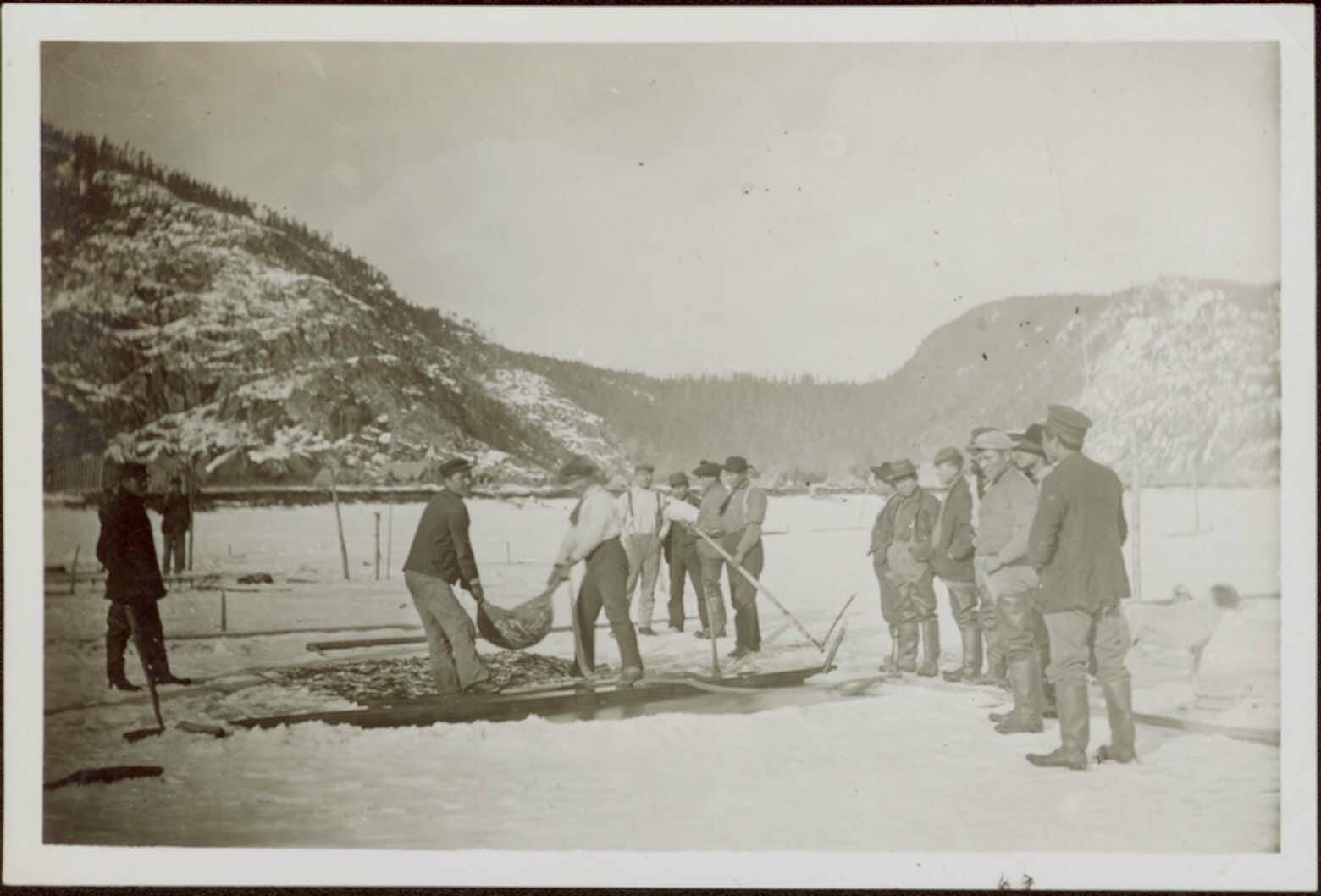

Every year in early spring, since before recorded time, Nisga’a have constructed camps along the banks of Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims (Nass River) to harvest and process oolichan. Lax-Da’oots’ip (Fishery Bay), where the glacial, blue waters of Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims meet the Pacific Ocean at Observatory Inlet, is the main harvesting centre for saak.

Historically, thousands of Nisga’a would spend months in Lax– Da’oots’ip, as they caught the first fish of the year. Nicole Morven, Harvest Monitoring Coordinator with Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department, recalls hearing from Elders that camps would operate for up to three months. “The women would be there too,” she says. “Helping to get wood and clean up, getting the poles and gear ready for the whole season.”

For us, it is a life-saving fish. It’s the first fish that comes in the New Year arriving as winter supplies are dwindling.

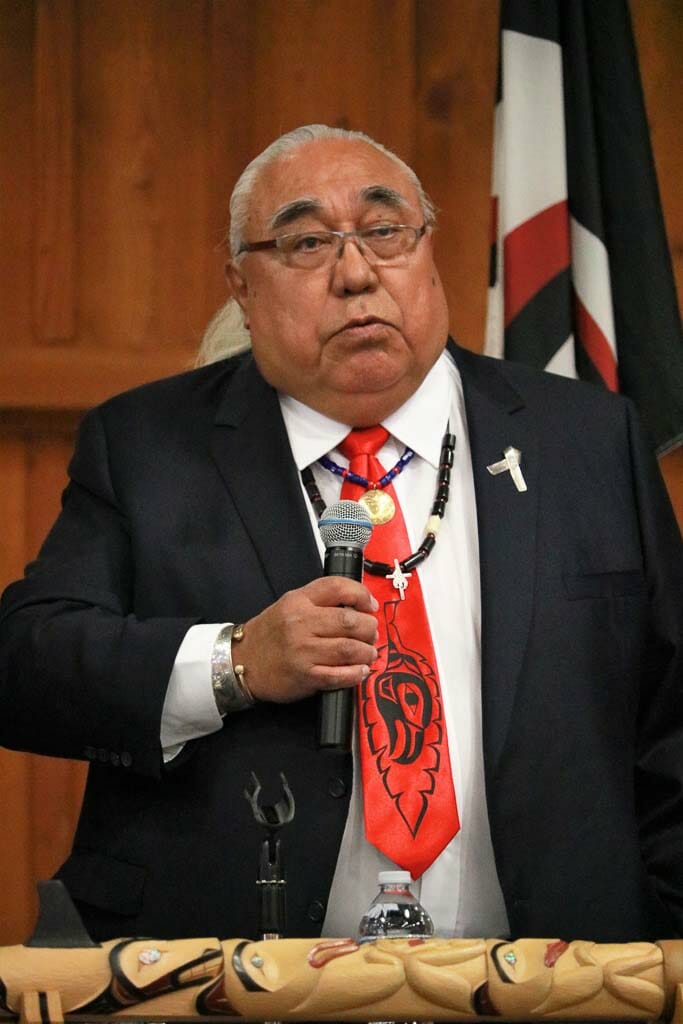

The Nation has always held complete control over the area’s oolichan run, providing them a source of wealth and power. “Of course there have been skirmishes back and forth over the years,” says Harry Nyce Sr., director of the Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department. “But the Nisga’a were always successful according to our history.”

Both the fish and the oil produced from processing it (t’ilx in Nisga’a) were valuable trading commodities between First Nations communities. Across the pacific northwest, “grease trails” formed where First Nations travelled, carrying their bentwood boxes of t’ilx for trade with other communities.

2009.7.1.132.

Although oolichan have always played a major role in the trading economies and culture of many First Nations, in Nisga’a territory the fish was never extensively exploited through Western commercial economies. Megan Moody, former Stewardship Director for the Nuxalk Nation, writes that a small commercial fishery for Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims oolichan existed in the first half of the 1900s until the Nisga’a Tribal Council Convention declared in 1955 that “no Nass River caught oolichans be sold commercially.”

Today, most of the oolichan caught and processed on the Nass River are distributed among community members or traded with neighbouring First Nations. Saak and t’ilx continue to play a significant role in the economies of coastal communities as Nisga’a citizens trade their resource for shellfish, herring, seaweed, and halibut.

I can’t ever imagine a day if they didn’t come back.

Nyce, a hereditary chief whose Nisga’a name is Sim’oogit Naaws, says the fish continues to be a mainstay of Nisga’a culture. “For us, it is a life-saving fish,” he says. “It’s the first fish that comes in the New Year arriving as winter supplies are dwindling.” Hoobiyee, the Nisga’a new year, starts during spring equinox with the migration of saak into the Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims (Nass River).

Edward Desson, Fisheries Manager for the Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department, says there is a distinct energy in the Nass Valley when the oolichan start their spawning journey. “It’s really hard to describe the buzz that goes on throughout the communities and how excited people get about the return of the oolichan,” says Desson. “I can’t ever imagine a day if they didn’t come back.”

For many First Nations however, that day has come.

Devastating Decline of Oolichan Populations South of the Nass River

In the 1990s, the slender, silvery-blue fish began to disappear from the waterways of the province. In the past, oolichan spawned in glacially-fed rivers from the Bering Sea to northern California, but today it is estimated that across British Columbia its population has declined by 98 per cent.

The exact reasons for the collapse are unknown, largely because of insufficient data and lack of monitoring rigour. Climate change, overfishing, industrialization, and by-catch are all considered contributing factors. However, because the small fish has never been a commodity in the Western economy, there has been little research into its disappearance. And so, First Nations who historically relied on the fish as a mainstay of their culture and trading economies, are left without reason for its decline and suffer the loss of the benefits it provides.

Besides being culturally significant, oolichan have historically played an important role in the health of First Nations community members. Oolichan grease is a rich golden liquid that in some cases can turn to the consistency of butter at room temperature. According to the First Nations Health Authority, the oil is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids, provides Vitamins A, E, and K, and, when smoked or dried, is an excellent source of protein and iron.

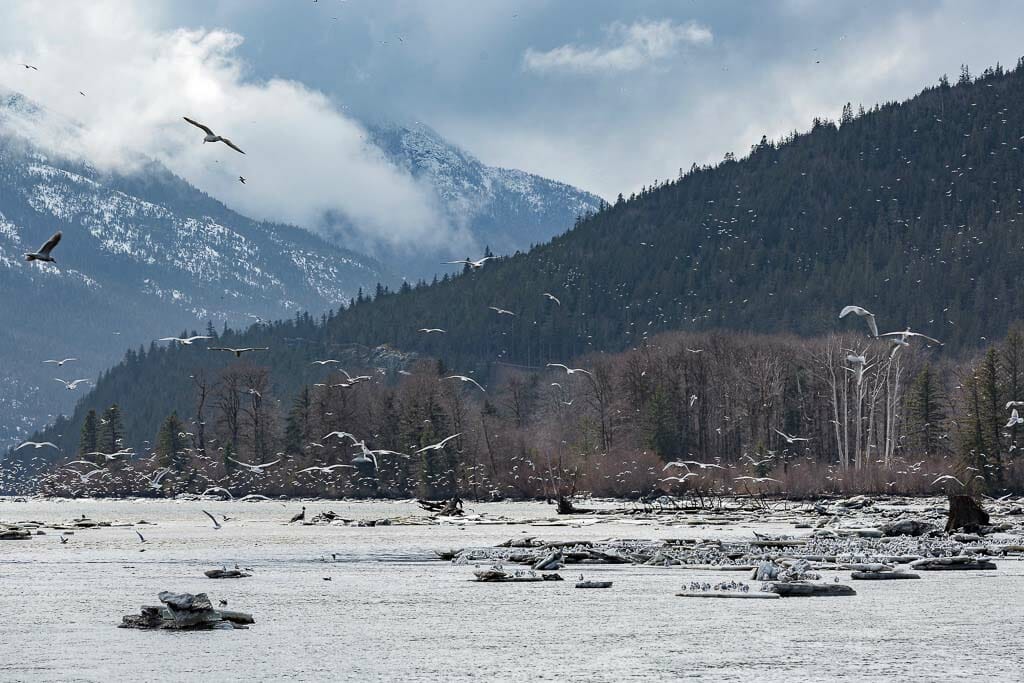

Oolichan also play an important ecological function, providing a large amount of energy rich food for marine and freshwater species including seagulls, seals, eagles, sea lions, porpoises, fin back whales, and even marine fish such as salmon, hake, and cod.

Despite significant declines in oolichan populations elsewhere, in the Nass Valley, the fish’s numbers have been high enough that the Nisg̱a’a have been able to continue the harvest of saak (oolichan) that has taken place on the banks of Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims for thousands of years.

Each spring, Nisg̱a’a citizens gather at Lax-Da’oots’ip (Fishery Bay) on the mouth of Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims. Morven, who monitors oolichan catch each year, says there are normally seven camps, though they don’t all set up each year. The camps are all Nisga’a, except for one Tsimshian camp from Lax Kw’alaams.

Morven says the work of harvesting and processing the fish is physically demanding. “I try not to bother them that much as they’re really busy and it’s a lot of work. It’s a back-breaking job.” It is not uncommon for crews to work into the early hours of the morning harvesting the fish as they follow the tides, fishing the oolichan on a dropping (outgoing) tide.

We as Nisga’a have taken only what we need, not what we want.

Lonny Stewart, who fishes saak as part of the team at Walter’s Camp in Lax-Da’oots’ip, says that fishers work to ensure a portion of each year’s run is able to spawn. The fishers are following Nisg̱̱a’a traditional knowledge, he says. “We as Nisga’a have taken only what we need, not what we want,” Stewart explains. He says that there is a third run of oolichan each season that is not harvested in order to ensure the fish are able to spawn.

Desson agrees and says that samples from oolichan caught at Lax-Da’oots’ip reveal that the majority of fish caught by Nisg̱a’a citizens have already spawned. It is possible this is one of the reasons the oolichan run in the Nass Valley has always been high enough to provide sufficient harvest for each of these camps and the family and community members for whom they provide.

Nonetheless, lack of data on the spawning biomass of the fish makes it difficult to assess true population over the past decades. Catch data has been variable and Desson suggests that if a year’s harvest volume has been lower than normal, the likely cause is fishing conditions. “The harvest will likely be lower [in 2018] because of changing ice conditions,” he says. “They couldn’t really fish through the ice and then they had to wait it out when the ice was breaking up.”

COSEWIC: A Threatened Species Facing Imminent Extinction

Because the Nisg̱a’a had not witnessed a decline in the number of oolichan harvested each year, they were surprised to learn in 2011 that the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), an independent advisory panel to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada that assesses the status of wildlife species at risk of extinction, had assessed saak as a “threatened” species. The designation suggests that the fish is “likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction.”

The Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government worried the designation could impact its citizens’ ability to harvest oolichan. In some cases, when a species is listed as “endangered” by the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA)—following an assessment by COSEWIC—all fisheries including First Nations harvesting for food, social, and ceremonial purposes, must be discontinued. Nyce says that losing its ability to harvest saak would cripple the mainstay of the Nisg̱a’a community.

The Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government requested a reassessment. Harry Nyce Sr. recalls that key Nisg̱a’a decision makers went to Ottawa to talk about the Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims (Nass River) oolichan. “They got an audience with Fisheries and Oceans and the COSEWIC folks and provided them with information about our oolichan harvests,” he says.

After the consultation, the Nass Valley oolichan was re-assessed as a species of “special concern,” which COSEWIC defines as a species that “may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.”

The COSEWIC assessment acknowledges the appearance of a stable population of oolichan in the Nass Valley, but suggests that decline in adjacent populations likely indicates existing threats in the marine environment where the fish spends 95 per cent of its life.

Desson says the re-assessment meant that “The Nisg̱a’a wouldn’t have any restrictions on their harvest.” Additionally, he notes, Nisg̱a’a were provided with the opportunity for funding from the federal government to research saak.

What the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department realized following the COSEWIC assessment was that there existed a need to gather stronger data on the spawning biomass of saak. They would need to begin collecting better data on the culturally and ecologically important fish in order to ensure a sustainable fishery could be maintained.

The data that existed to-date was catch per unit effort data, the data that Morven collects each year in Fishery Bay. Desson says it’s a problematic method to determine species abundance because “there’s a lot of effort that goes into catching the fish and it’s hard to determine the actual true-decline signal from these data.” Catch per unit effort data are sufficient to determine how much is being caught, but can’t accurately determine the number of oolichan spawning.

Collecting Data to Deepen Local Knowledge

What the COSEWIC assessment revealed is that the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department would need to begin collecting spawning data on oolichan in order to ensure a healthy population and maintain the Nisg̱a’a citizens’ ability to harvest.

In 2013 Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife decided to undertake a spawning stock biomass research project to determine the exact number of oolichan in Ḵ’alii-Aksim Lisims (Nass River). “That’s when we started doing our own research,” says Desson. “So when [the oolichan stock] is reviewed again we’ll have answers and solid scientific backing for our argument that it shouldn’t be included with the Skeena population.”

When [the oolichan stock] is reviewed again we’ll have answers and solid scientific backing for our argument that it shouldn’t be included with the Skeena population

To determine oolichan abundance, Desson partnered with LGL, an environmental research company who has worked with the Nisg̱a’a Nation since 1992. The project would determine multi-year Nass River oolichan abundance by analyzing larval samples collected from the river.

The project was modelled on a similar research program on the Fraser River. “We took what they do and modified it for the needs of the Nass and its specific geography,” says Cam Noble, who worked on the project as a fisheries biologist. “We started doing larval tows—that’s how you get to the number of oolichan that spawned on a yearly run.”

The research started in 2013 as a pilot project and was continued in 2014 by partnering with the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk. During 2015 and 2016, the team had collected a lot of samples, but had underestimated how much time it would take to process the samples. “We were in a bit of a bind and that’s when Coast Funds came in,” Desson recalls. “We were able to come up with estimates of biomass and then have a strategy moving forward so we didn’t end up with a pile of samples in our back room that we couldn’t deal with.”

Greater Understanding of a Keystone Species

The results of the research project, which is still continuing in 2018, were surprising even to Desson. “We found that…over the last three years the biomass of oolichan has risen,” he says. “We were quite surprised to see how high they were.” The estimated biomass in 2015 was 1,322 tonnes and 2,732 tonnes in 2016. These numbers represent a significant increase from 2014 when oolichan biomass was assessed at 156 tonnes.

Noble says there were other surprises for him on the project. He learned that much of the harvesting of oolichan takes place after they have spawned, an example of Nisg̱a’a traditional ecological knowledge. Noble, who has worked primarily on Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife projects during his seven years with LGL, says this means that harvesting rates have less impact on population sizes than he previously thought. “They’ve spawned, they’re going to die anyway and now the Nisg̱a’a put their nets in the water and scoop them up.” Noble says it’s the only fish species he’s aware of in BC where harvest occurs post-spawn.

That information will play an important role when COSEWIC reassesses the status of Nass River oolichan in 2023, as will the data collected from the project. “There will actually be some hard population data upon which we can assess the status,” says Noble.

We found that…over the last three years the biomass of oolichan has risen.

Through the project, Desson, Noble, and other Nisg̱a’a researchers discovered that the spawning population of oolichan is highly variable, much like the sockeye salmon run. “I’m not saying it’s a boom and bust cycle,” says Noble. “But it is many orders of magnitude different in the few years of data we’ve collected so far.”

Desson says the knowledge of the variability of spawning cycles allowed them to refine their sampling protocol. “In looking at the data we were able to eliminate some of our samplings as unnecessary.” Technicians now better understand where and when to draw larval samples from the river. “We were able to separate where the main flow of larval drift was, so we can just sample those locations.”

That, Desson says, has implications for cost savings as well. He estimates that the research results allowed them to save one third of their annual budget on the project. “Now we can just get out there relatively cheaply and easily, grab our samples, and get back,” he says. “It gives us time to process them within our regular budget. We can do this year in year out and not have to look for extra funding.”

Charles Morven, chief councillor of the Nisg̱a’a village of Gitwinksihlkw and Chair of the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Committee says the project was an essential one for providing stock assessment and is going to “get as close to actual numbers of oolichan as there are.”

Harry Nyce Sr., says the project was effective at putting together data sets for historical reference and providing more ways to maintain the resource. “That’s extremely important for us,” he says “and we’re appreciative of Coast Funds to recognize that and help us do the work that we’re doing.”

Desson hopes that other Nations who want to undertake similar research projects will speak to the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department first. “It would be worthwhile to review some of our reports and talk to our biologists about the protocol so they don’t have to go through those growing pains,” he says. “Now that we’ve refined the protocol, they could use what we’ve done…It would save them a lot of time and money.”

Cultural Outcomes

When species are assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, before being proposed for listing under the Species at Risk Act, First Nations are at risk of losing access to culturally significant species. The oolichan are central to Nisg̱a’a culture; their arrival every spring signals the start of Hoobiyee, the Nisg̱a’a new year.

By gathering sufficient data to better understand the oolichan population in their territory, this project is helping to ensure that the relationship Nisg̱a’a have always had with the saviour fish can be maintained. The harvesting of oolichan is managed under traditional Nisg̱a’a resource law and is a defined treaty right under the Nisg̱a’a Treaty.

Learn more about access to traditional foods outcomes.

Economic Outcomes

By partnering with LGL on this research project, the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department was able to accomplish its research objectives. The Nisg̱a’a Nation has worked with LGL since 1992, when the company worked on pre-treaty initiatives. LGL was involved with the re-assessment of oolichan by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and played an essential role in the technical analysis of existing catch data.

By protecting its access to traditional harvest of oolichan, citizens of the Nisg̱a’a Nation are able to maintain historical relationships with other First Nations. Trading is still an integral part of the oolichan annual harvest.

Learn more about partnership outcomes.

Environmental Outcomes

Oolichan are a forage fish that play a bedrock ecological role as food for almost every other predatory creature in the sea. “It’s incredible actually,” says Desson. “The oolichans come in and spawn, then the seals, sea lions, seagulls, and eagles all move in to feed on them.” Beneath the surface the dead oolichan are playing a role as well. “They feed the crabs, then the halibut move in, and actually it provides the Nisg̱a’a with an opportunity to get some of these other species too,” Desson points out.

Careful monitoring of the traditional Nisg̱a’a fishery, and data collection of the oolichan population ensure that the oolichan population will not be reduced to a threatened level on one of the few river systems where their numbers are still abundant. By providing a baseline spawning stock assessment, the Nisg̱a’a can effectively monitor any future impacts to the species from fishing, climate change, industrial development, and by-catch. This ensures that the many marine, freshwater, and land species who rely on the oolichan for subsistence can benefit from a stable population.

Learn more about scientific research outcomes.

Social Outcomes

Year round employment was provided for three previously seasonal technicians. Typically, fisheries work is seasonal, as there is not much to be done during winter freeze. As Cam Noble points out, “the nice thing about this work is that it’s not particularly time-sensitive, so it can be done in the shoulder season.” He says year-round employment is “almost unheard of in our business up there.”

Additionally, three people received two days of training on the identification of oolichan eggs and larvae. They were also taught appropriate processing and handling methods to ensure samples were not lost, and safety precautions were taken.

Learn more about job creation outcomes.

In 2016, Coast Conservation Endowment Fund Foundation approved funding totalling $91,000 toward Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government’s oolichan spawning stock biomass research project.

Online Resources

- Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department

Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department - Nisga’a Lisims Government - Nisga’a Lisims Government

Nisga’a Lisims Government - Eulachon (Nass/Skeena Rivers population)

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Aquatic Species at Risk - COSEWIC Assessment - Eulachon

COSEWIC Assesment and Status Report on Nass/Skeena Eulachon - Government of Canada - COSEWIC

About the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada - Government of Canada - SARA

About the Species at Risk Act - Eulachon Past and Present

aster’s Thesis Project, Megan Moody - ‘Salvation Fish’ That Sustained Native People Now Needs Saving

National Geographic, July 2015 - By the Light of the Candlefish

Toque & Canoe, April 2017 - How to Bring Back the Eulachon?

Globe and Mail, May 2011 - Oolichan… more than just a fish

WWF-Canada Blog, May 2011 - Climate Change, Marine Predation, Trawl By-catch, and Changing Habitat ‚ The Fate of Nass Eulachon?

Nisga’a Lisims Government - Hoobiyee

Hoobiyee Description, Nisga’a Lisims Government - First Nations Traditional Foods Fact Sheets

First Nations Health Authority - How to make "Oolichan Grease"

Blue Moon, March 2004 - Saving Eulachon

Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance, October, 2013.

Published On July 10, 2018 | Edited On February 27, 2026