Nisg̱a’a Nation’s fishwheel program uses external tags, radio telemetry, salmon monitoring, and DNA collection as part of a sophisticated mark-recapture program to estimate annual returns and predict future management and conservation of salmon populations returning to Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims Nass River. The research helps to determine harvest entitlements for Nisg̱a’a Treaty Fisheries, support food security for Nisg̱a’a citizens, and sustain salmon runs for years to come – benefitting all harvesters of Nass salmon.

River Of Abundance: How Fishwheels Are Driving Nisg̱a’a Nation’s Salmon Stewardship

Estimated Reading time

35 Mins

Nisga’a lands cover 200,000 hectares and reach from the mouth of the Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims Nass River and inland to the Hazelton Mountains. The main communities are located in the Nass Valley and include the villages of Ging̲olx, Lax̱g̱alts’ap, Gitwinksihlkw, and Gitlax̱t’aamiks.

At a Glance

As Pacific salmon face threats from climate change, overfishing, and habitat loss, the Nisg̱a’a Nation is using Traditional Knowledge and Western science to determine future management and conservation of salmon populations for generations to come.

Along the rocky banks of Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims Nass River, Nisg̱a’a Nation’s Fisheries and Wildlife Department operates fishwheels – structures with rotating baskets that catch and release fish unharmed – to monitor salmon returns, migration to spawning grounds, en route mortality, and population trends for specific tributary stocks. In partnership with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and BC Fisheries, this program supports Nisg̱a’a Treaty management projects under the Nisg̱a’a-Canada-BC Joint Fisheries Management Committee (NJFMC).

In the recent decade, larger salmon species like Chinook have seen the largest population declines, with total abundance numbers on the Nass River dropping 37 per cent. Using data from the fishwheels, the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department can safeguard salmon species like Chinook by predicting future returns and managing harvest amounts for fisheries on the Nass.

Salmon are sacred to Nisg̱a’a people. Elders, like Chief Jacob Nyce, and biologists, like Niva Percival and James Griffin, are practicing their inherent right to steward their lands and waters, so that salmon continue to return to the ‘River of Abundance’ for years to come.

Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims: The River of Abundance

Knowledge keeper and respected Elder Sim’oogit Baxk’ap Chief Jacob Nyce, 96, sits comfortably in a recliner chair by a large window. His home is nestled in the village of Gitwinksihlkw and overlooks the steady flow of Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims Nass River.

Sunlight filters softly into the room, revealing healthy plants and hundreds of family photographs lining the walls and displayed proudly on shelves. One of his companions, a small black and white dog called Covid, sits perched on the windowsill, ready to alert his owner of any new visitors. Today, Hereditary Chief Jacob Nyce is sharing stories about salmon.

“I remember one time, day after day, we ate salmon. My brother complained, so my mother went in her room and showed all the money she had. She told him, ‘We got no store here. We can’t eat money.’ Then she listed the animals that eat fish, especially the bear. ‘See how fat they are, all they eat are salmon.’ My brother never complained again after that. Salmon is the food that kept our people alive before [European] contact.”

Providing hundreds of thousands of salmon to the Nisg̱a’a each year, the Nass River flows almost 400 km from the Coast Mountains into the Pacific Ocean from Portland Inlet. The third largest river in British Columbia, and home to oolichan, steelhead, and five species of Pacific salmon, the Nass is abundant in natural resources that have sustained the Nisg̱a’a people, and neighbouring Nations, for thousands of years.

Nisg̱a’a people have stewarded these lands since time immemorial, spending generations understanding and caring for the delicate ecosystem. Surrounded by mountain ranges known as the Saviour Mountains to the Nisg̱a’a Nation, the Nass River is said to have been created in a time before light was brought into the world.

Txeemsim, a supernatural being, shaped the water channels of the Nass River as well as the surrounding mountains. It is said that Txeemsim made the waterways specially so that salmon would spawn.

This unique geography positions two of Nisg̱a’a Nation’s villages, Gitwinksihlkw and Gitlax̱t’aamiks, near an active volcano, Wil Ksi-baxhl mihl where the fire ran out (Tseax Cone). For thousands of years, the volcano’s nutrient-rich lava flows have shaped the Nass River, creating ideal conditions for salmon spawning grounds.

Salmon are an important part of Nisg̱a’a Nation’s Treaty Fisheries – which were negotiated with Canada and BC as part of the Nisga’a Final Treaty, and implemented in 2000 – and food security, impacting the social, cultural, and economic well-being of the community. Chinook salmon, for example, are one of the first and largest fish sources that return to the Nass for spawning and mark the start of the salmon harvest in the region.

To capitalize on the plentiful salmon population, European settlers established a string of canneries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the Arrandale and Mill Bay canneries near Ging̱olx, where Nisg̱a’a, Chinese, and Japanese people worked long and hard hours.

“Them days, there was so much fish that the people that were canning the salmon couldn’t keep up with it,” says Chief Jacob Nyce. “I remember Arrandale, there were killer whales and mudsharks that would beach themselves. Eat so much salmon, they would beach themselves after. They don’t know why.”

Across British Columbia and throughout international waters, modern commercial fishing practices and a warming Pacific Ocean have contributed to declines in salmon populations. For the Nass River, salmon returns dropped to less than 900,000 in 2018 and 2019 from historical averages of two to three million salmon raising concerns for the Nisg̱a’a Nation.

Through fishwheel, catch monitoring, and spawning ground counting programs, in combination with mark-recapture techniques, radio telemetry, and DNA collection, Nisg̱a’a Nation’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife is combining Traditional Knowledge and Western science, keeping a close watch on salmon migrating through their lands.

Addressing the Decline: Nisg̱a’a Nation’s Fish Population Management

In recent decades, habitat destruction, overfishing, and climate change have negatively impacted salmon returns in British Columbia, resulting in the collapse of some salmon populations in the 1990s. In 1999, salmon harvest rates on Skeena River fell to 0.1 per cent of historic levels, and harvest rates for Chinook on the Quinsam River (Vancouver Island) dropped to less than 20 per cent. The knock-on effects devastated salmon numbers well into the 2020s – and today, about half of Pacific salmon populations remain in a state of decline.

“Since 2011, the Nass, Skeena, and Fraser rivers have been in low productivity for some salmon like Chinook and sockeye,” says Richard Alexander, a senior stock assessment biologist for LGL Limited and a technical advisor to the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government. “We’re seeing quite a shift in different species abundances because of the ocean warming conditions, habitat loss, and overfishing.”

In the Nass River, Chinook salmon’s total abundance is 37 per cent below average: or about 13,000 fish based on average total runs from 1992-2014 (35,000; range: 16,000-52,000) compared to average total runs from 2015-2024 (22,000; range: 12,000-35,000).

Today, Nisga’a monitoring staff report that fish leaving and returning to spawn are smaller and potentially less healthy than past returns. With the changing water conditions, juvenile Chinook salmon are using more energy to survive the warmer waters in the ocean, while also facing poorer food sources during their marine growing phase of their lives. During the marine growing phase, Chinook typically live in the Pacific Ocean for two to four years before returning to the Nass River to spawn as an adult.

“Salmon really need to be a certain size to go to sea to take on that part of their journey from fresh water to salt water as they physically change form to adapt to salt water,” says Richard. “Success of survival is being a large enough size.”

A Chinook salmon’s adult size also greatly affects the reproductive capacity of the fish, impacting the production of eggs and milt.

Sim’oolgit Hleek Hereditary Chief Harry Nyce Senior, Director of Fisheries and Wildlife for Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, grew up fishing along the Nass and Skeena Rivers.

“When I started fishing, I was catching Chinook in the Nass River around 80 pounds. But now we’re lucky to get to 60 pounds,” he says.

Historically, a healthy Chinook salmon can grow up to 99 pounds (45 kilograms) and reach seven years in age. For fishers, a smaller fish yields less meat. As a consequence, fishers need to harvest more fish to meet their family’s needs.

As fewer and smaller salmon complete their life journey to the spawning grounds, the Nass River is at risk of no longer sustaining the amount of salmon needed for Nisg̱a’a food, social, and ceremonial (FSC) purposes, alongside local commercial and recreational fisheries.

We have an inherent right to this land, and that gives us the right to protect the land, to protect the salmon.

Nisg̱a’a Nation manages the Nass River salmon and steelhead stocks in partnership with the governments of Canada and British Columbia. Using data from the fishwheel monitoring program, the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government has carefully managed the Nass River for more than 30 years, tracking the population and health of five species of salmon (sockeye, Chinook, chum, pink, and coho) and summer-run steelhead (a sea run migrant of rainbow trout).

“When we took over our management role in 1992, we had [average total runs of] 800,000 Nass sockeye, give or take,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “This year, the total run size estimate is just over 400,000 returned. That’s half. It’s a challenge.”

After signing the Nisg̱a’a Treaty and Nisg̱a’a Nation Harvest Agreement (NHA) with Canada and British Columbia in 2000, the Nation was allocated 10.5 per cent for FSC fisheries to a maximum of 63,000 sockeye (or 7.4 sockeye per Nisg̱a’a person in 2025), plus 13 per cent of each year’s adjusted total allowable catch of Nass sockeye salmon for FSC or economic fisheries.

“That was the formulas, according to the rules of negotiations,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “That’s why we ended up with the allocations that you see. So, when returns were 800,000, we got up to 23 per cent of it, like in 2002 with 195,000 Nass sockeye allocated, that’s not bad. But an allocation at 400,000 – that’s only 60,000, or 7.1 sockeye per Nisg̱a’a person. Well, it’s not enough.”

In 2020 and 2021, Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government made the difficult, but necessary, decision to recommend closing commercial fisheries and sport fishing of Nass salmon in order to protect the salmon populations and prioritize fish to feed the community. Total Nass salmon runs had dropped to less than 900,000 in 2018 and 2019 from an average of 2 million (range: 664,000 to 3.8 million) Nass salmon from 1992 to 2017. Specifically, Nass sockeye (373,000) and Chinook (22,000) average returns from 2018 to 2021 were well below average.

“We had to really convince [Crown] governments to say ‘no’ to more commercial and sport fishing, then shorter sport fishing, then none at all,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr.

Despite external factors like overfishing in international waters and climate change, Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government and their Fisheries and Wildlife Department are using their fish monitoring programs combined with thousands of years of ancestral knowledge to take a proactive and cautionary approach to reducing the risk of long-term fishery closures. The Nisg̱a’a Treaty has provided secure access to salmon each year. Since 2000, Nisg̱a’a Treaty entitlements of Nass sockeye have averaged 84,000 (range: 33,000 to 195,000) with 2025 allocation only 69,000 including NHA allocations (or 8.1 sockeye per Nisg̱a’a person). Total Nisg̱a’a Treaty allocations of Nass salmon from 2000 to 2024 have totalled 4.6 million (2 million sockeye, 1.9 million pink, 159,000 Chinook, 357,000 coho, and 99,000 chum) or 184,000 average each year (84,000 sockeye, 75,000 pink, 6,345 Chinook, 14,300 coho, and 4,000 chum).

The most prized fish for our food fisheries is the Chinook, and that’s just been going straight down in numbers. We’ve got to provide a little balance here.

“[Before] we assumed our management, we were just advisors to DFO,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “Our elders and our fishers said, ‘Why don’t we manage our fishery like we do with the mountains and the valleys?’ You see, they are all owned by somebody. That mountain behind me, that’s my family’s mountain. It’s called Minhl Angeekaskw. There’s a stream through that mountain that has Chinook and steelhead. So that’s one of those things, the elders kept finding that we need to get back our management control and then [we would] have a lot more to say. Because we’re the ones living here.”

Nisg̱a’a Fish Allocations for Salmon

| Species | Sockeye | Pink | Chinook | Coho | Chum | |

| 1. | Nisg̱a’a share (%) of return to Canada | 10.5% | 0.6% | 21.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% |

| 2. | Return to Canada Small (run size) Large (run size) |

160,000 600,000 |

300,000 1,100,000 |

13, 000 60,000 |

40,000 240,000 |

30,000 150,000 |

| 3. | Nisg̱a’a fish allocations at small and large returns to Canada Threshold (at small return to Canada) Maximum (at large return to Canada) |

16,800 63,000 |

1,800 6,600 |

2,730 12,600 |

3,200 19,200 |

2,400 12,000 |

Table: An extract from the Nisg̱a’a Treaty (Chapter 8: Fisheries) illustrating negotiated FSC numbers. Starting in 2000, the Nisg̱a’a now have a defined 10.5 per cent share of Nass sockeye based on Total Returns to Canada (TRTC), capped at a specific allocation (63,000) based on negotiated ‘at large TRTC’ (600,000). The Nisg̱a’a formula for sockeye FSC allocation equates to a maximum of 7.4 sockeye per Nisg̱a’a citizen, given a population of 8,500 (2025).

Fishwheels and Salmon Monitoring

Since its inception in 1992, the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department (NFWD) has employed an average of 45 Nisg̱a’a members, seasonally and full-time, to run the stock assessment test fishery, catch, and escapement monitoring program. In more recent years, Nisg̱a’a biologists like James Griffin have stepped into more technical and leadership roles at NFWD.

“I started with the program as a technician in 2018,” says James. “There is a lot of overlap and shared obligations between [technicians and biologists]. However, the biologist’s scope of work is geared more towards data analysis and project coordination.”

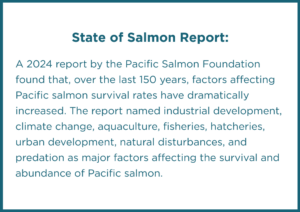

The test fishery that is used to guide all Nass River salmon fisheries, includes two fishwheels anchored alongside the rocky edges of the Nass River beside the village of Gitwinksihlkw. Three to four additional fishwheels are operated at Grease Harbour, about 18 kilometres up the river. The mostly aluminium structures are large, consisting of 3 x 3.5 metre baskets attached to an axle that floats in the river on pontoons. The fishwheels operate each year from June to mid-September, with five to six crew members working on each site. By August, there are 25 technicians rotating between working the wheels, conducting salmon escapement surveys, fish catch monitoring, video counting at the Kwinageese weir, crew training, and monitoring beaver dams to ensure fish have clear passage.

The team is a mix of emerging technicians, biologists, and legacy staff, some of whom have been working the wheels since they were built and installed in 1992.

“Before 2000, the fishwheels were made of wood,” says Tim Angus, one of the crew leaders who has been working this program for over 30 years.

While working the fishwheels, the team moves with efficiency and ease. After the fish are captured in the wheel’s basket, they slide from a wooden jumper board into a live tank, which acts as a holding space before the fish are collected for examination and tagging. All species of salmon are tagged and sampled at the test fishery fishwheels, allowing biologists to estimate salmon returns to Gitwinksihlkw and project Total Returns to Canada (TRTC) to estimate Nisg̱a’a Treaty entitlements.

“The wooden portion above the live tank is referred to as the “jumper board” because it prevents the fish from jumping out of the live tank,” says James.

The technician identifies the fish, calling out the species and number of salmon. At the front of the wheel, a senior technician or biologist records the data at a station referred to as the birdhouse.

“The birdhouse can be a stressful position to record data, especially during peak salmon passage,” says James. An in-depth knowledge of fishwheel routine and sampling protocols is required to record data.”

“Last year the wheels caught over 12,000 fish in a day,” says James. “A day or so later, the wheels caught 10,000. That’s around 300 fish an hour.”

Unlike fish caught in gillnet fisheries, fish caught in fishwheels are unharmed and quickly released back into the river to continue their journey to their spawning grounds. On occasion, a salmon is caught and brought to the fish trough for tagging and sampling (length, age, and genetics).

Chinook salmon are tagged at the fishwheels with a numbered external tag, called an operculum tag. In 2024, over 300 Chinook received a radio tag that was inserted into their stomach. These radio-tagged fish were tracked throughout the Nass watershed using fixed telemetry stations installed along their migration routes as well as by helicopter, boat, and foot surveys. Radio tags provide geospatial data about a fish’s movements and spawning location, helping biologists to better understand why Chinook returning populations are currently so low.

“This represents just one of over 25 different programs that are conducted by NFWD each year,” says James.

Tagging and sampling helps the Nisg̱a’a better understand Nass salmon, including the fish’s age when returning to spawn, migration patterns, and en route mortality. The data collected is included in NFWD’s stock assessment weekly update report, with support by LGL Limited. The report is shared publicly with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, and other fisheries organizations including commercial, sport, and other First Nations. In partnership with DFO and British Columbia, the data helps NFWD to determine future management and conservation of Nass salmon populations, determine FSC counts, and advise on allocations for commercial and sport fishing.

| NFWD Fisheries Program Goals: | |

| 1. | Monitor Nass River salmon and steelhead returns to spawning goals and provide sustainable fisheries. |

| 2. | Provide better fisheries management including harvests of Nass salmon and non-salmon fish in commercial, sport, and other fisheries. |

| 3. | Determine run size, timing, and Nisg̱a’a Treaty Salmon entitlement estimates. |

| 4. | Determine factors limiting healthy salmon and non-salmon production in the Nass watershed. |

| 5. | Provide training and employment for Nisg̱a’a citizens. |

One of the most prolific fishwheels, affectionately referred to as the “Honey Wheel,” requires daily maintenance. The wheel is positioned at a bottleneck of the river, tucked snugly behind a curve in the rocks. The bottleneck causes the current to move rapidly through the wheel, creating a high amount of pressure and an optimal yield of fish.

Today, a part of the fishwheel basket’s frame has snapped and created a large hole in the net, requiring significant repairs involving the whole team. Repairs are made immediately to prevent fish from escaping and to limit any further damage.

A good deal of innovation is required to fix the pole. Using a rope to clamp the frame together before drilling, the team works together to source tools and solve the problem. Senior Technician, Kirby Gonu, uses a series of clove hitch knots to fix the net before moving swiftly to the next task. Not soon after, Bertram Percival stands on top of the wheel and drills holes in the metal frame, preparing to attach a replacement pole.

After 30 minutes of repairs, the technicians return to counting the fish, lifting around six fish per net, weighing anywhere between five kilograms to 27 kilograms. The work is hard yet rewarding.

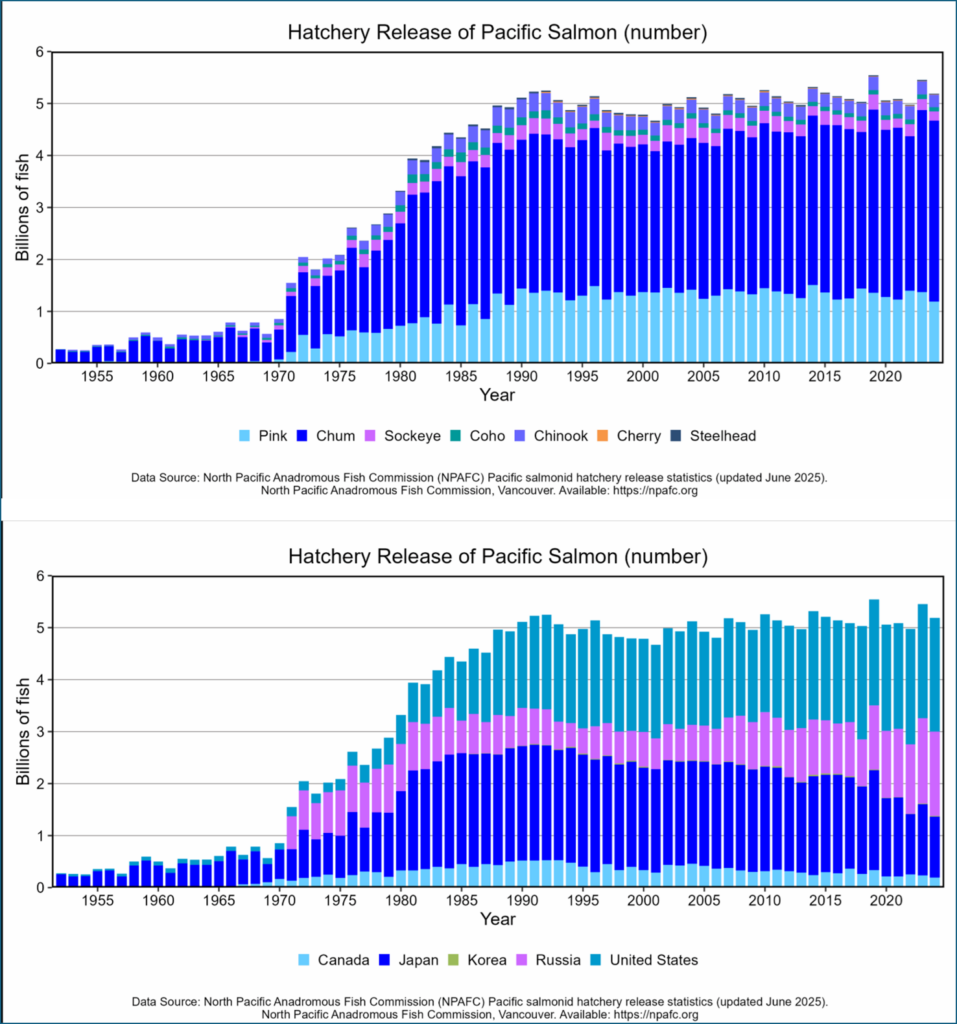

In recent years, pink salmon have dominated the population count, while more valued fish for FSC and economic purposes, like sockeye and Chinook (only FSC), have decreased. One theory is that as pink salmon increase in numbers, they consume the food sources in the ocean that larger salmon like Chinook rely on for survival and growth.

“That’s what we’re seeing,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “The most prized fish for our food fisheries is the Chinook, and that’s just been going straight down in numbers. We’ve got to provide a little balance here.”

Other river systems along the Pacific coast, especially in Alaska, have large hatcheries operating primarily for pink and chum salmon, which have released two to three billion juvenile fish each year since the mid 1980s, creating stiff competition for food in the ocean.

“Up and down the coast, they’re releasing these massive [amounts] of fish in billions of numbers. All while they’re competing for the same food in the mid-Pacific,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “How can the wild salmon survive that?”

NFWD’s analysis from the collated fishwheel data and radio tags helps to better understand how changing climate conditions – such as high water temperatures and low water levels – affect the en route mortality of adults trying to reach their spawning grounds. Other factors like large commercial fishing interceptions, including trawlers that can cause habitat damage, may also affect Nass salmon productivity.

“We warned them [DFO], what they were doing,” says Elder Chief Jacob Nyce. “They let these big boats with big nets right up Rivers Inlet. The nets were so deep when they were set, they destroyed that habitat down there. They did that for 45 years.”

Salmon, Gwaxts’agat, and Wil Ksi-baxhl mihl Where the Fire Ran Out

Elders like Chief Jacob Nyce carry generations of Nisg̱a’a knowledge and leadership, playing an important role in the reclamation of Nisg̱a’a stewardship authority, following the devastating impacts of colonization.

“That cultural part of my life, when I grew up, was strong. I became Chief after my brother passed,” he says. “Passed down generation after generation, I was given the chief name Sim’oogit Baxk’ap.”

When Chief Jacob returned from residential school, his uncle, who was in his late 80s, shared many stories which have been held by his family for hundreds of years. One of the stories, that Chief Jacob shares today, is about salmon.

“Chinook salmon had a habitat here,” says Chief Jacob Nyce, pointing in the direction of the village’s information centre and shaping his hands to show the flow of water. “There used to be creeks running up into the lake.”

“Kids, they’ve got nothing to play with. They started playing with these big salmon. One of them had an idea to cut the back of the salmon.” Chief Jacob Nyce slices his hand in the air.

“Now, if you cut the bark off the birch tree, it’ll roll up. They would get pitch from Jack pine, put it on the end of the birch.” With the mixture prepared, the birch would light up like a candle. The children returned to the creek.

“They would go back to the creek, catch one of these big salmon, slit the back, and put that thing in. Watch it swim up the river, smoke rising from its back. They were all standing and laughing.”

An Elder noticed what was happening and warned the children. “That’s a curse you’ve created. It’s going to kill a lot of our people.”

Not long after the Elder’s warning, the neighbouring volcano, Wil Ksi-baxhl mihl, erupted.

“The volcano erupted,” says Chief Jacob Nyce. “It’s a warning that we should never play with anything that we’re going to eat. Never.”

When the volcano erupted over 260 years ago, two Nisg̱a’a villages were destroyed and 2,000 people perished.

“My late father-in-law told us how that volcano stopped. Because, if you go down there to see [the lava flow], it’s just like there’s a wall there. Instead of sliding down, it just stopped,” says Chief Jacob Nyce.

“There was a wolf living there. He hollered up to speak to the mountain bird, Gwaxts’agat. Big, huge mountain bird. He was supernatural. The wolf challenged the bird, ‘Why don’t you stop that lo’oba mihl?’ That’s what we call lava flow. ‘Can you see what’s happening? It’s killing a lot of our people.’ So that big bird extended his nose.”

Chief Jacob laughs and points to his own nose, “Pinocchio, I call it. He extended his nose and stopped the lava from going any further.”

“My family holds that story. That’s why, if you go up to the gymnasium,” he points behind his house. “The very top of the totem pole, you see that nose? That’s the one. That bird stopped the lava flow.”

Standing exceptionally tall and overlooking the village of Gitwinksihlkw is a totem pole that was raised in 1992. Right at the top, with his long nose, is the supernatural being, Gwaxts’agat, watching the village.

Learning from Ayuuḵhl Nisg̱a’a Ancestral Knowledge

The stories Chief Jacob shares are deeply rooted in values of reciprocity and Ayuuḵhl Nisg̱a’a ancestral knowledge. Values that have been upheld by Nisg̱a’a peoples since time immemorial.

As a biologist-in-training, registered with the BC College of Applied Biologists, James Griffin received technical guidance from Richard Alexander and Stephen Kingshott, senior biologists from LGL Limited, as well as mentorship from his NFWD colleagues.

“My senior crew leaders and technical staff at Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife have been instrumental to my training and development since I started with the program,” shares James. “Individuals such as Tim Angus, Kirby Gonu, Ben Gonu Jr, Isaac Gonu, the late Simon Haldane, and the late Brian Adams have taught me a great deal over the years and helped me reach my current position.”

Elders’ leadership and community mentorship, paired with a range of engaging programs offered by Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, help youth and emerging stewards to reclaim their inherent right to protect their land and carry forward their important cultural practices.

“We have an inherent right to this land,” says Chief Jacob Nyce, “And that gives us the right to protect the land, to protect the salmon.”

Institutions like Wilp Wilx-o’oskwhl Nisg̱a’a Institute (WWNI) that provide courses covering Nisg̱a’a cultural practice, language revitalization, and First Nations environmental philosophy and knowledge, can also encourage the convergence of Traditional Knowledge and Western science in emerging stewards’ everyday practice.

“That’s my hope, to see that happen. The continuous encouragement for our young people, especially,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “For example, we have Niva Percival. She is one of the first Nisg̱a’a biologists.”

In addition to her work with NFWD, Niva runs a program at the local school, offering elementary and high school classes.

“I am the lead fisheries biologist for community outreach regarding the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries program concerning Nisg̱a’a students from preschool to post-secondary within the Nass Valley,” says Niva.

Community outreach includes presentations in classrooms and information booths at events, which are “geared towards getting the students excited about fisheries science and to increase [their] interest in becoming a future Nisg̱a’a fisheries biologist,” she says.

Niva was the first recipient of the Lisims Fisheries Conservation Trust Fund bursary, with James following shortly after. The bursary, which supported their post-secondary studies to become biologists, allowed Niva and James the opportunity to remain connected to Nisg̱a’a lands, working for NFWD on what may be considered one of the most successful test fisheries in the world.

Through donations made by research partner LGL Limited, NFWD is able to continue funding post-secondary education for Nisg̱a’a citizens interested in becoming fisheries biologists.

“That’s what Wilp Wilx̱o’oskwhl Nisg̱a’a Institute is doing. That’s what Dr. Deanna Nyce and her team are doing, currently, infusing Traditional Knowledge into it. In fact, WWNI is building a new university here, in the next few years.”

James’ brother, Chris Griffin, is currently pursuing an undergraduate science degree whilst also working as a technician for NFWD. When his studies are complete, Chris will join the ranks of the biology team.

Chief Harry Nyce Sr expects that, once the university is built nearby, the demand for youth engagement in fisheries and wildlife will increase, creating new pathways for Nisg̱a’a citizens to continue stewarding their lands and waters.

“Overall, getting the youth a little bit more engaged is a priority,” says Chief Harry Nyce Sr. “At the end of the day, we’ll see that the wild salmon continue to return to the Nass.”

With more than 30 years of data from the fishwheels, it’s programs like the Chinook radio tagging funded by Coast Funds in 2024 that have allowed Nisg̱a’a Nation to make informed and efficient harvest and spawning ground estimates. Working in partnership with Canada and BC, the program continues to serve the community’s Treaty Fishery, enabling food security for all Nisg̱a’a citizens and ensuring that salmon continue to come back year after year, sustaining future generations.

“People cannot live without salmon, even today,” says Chief Jacob Nyce, “Salmon, is gift of God. You cannot destroy it. Once you’ve destroyed it, it will never come back.”

Through Coast Funds’ Conservation Fund, the Nisg̱a’a Nation invested $400,000 in 2024 to conduct radio telemetry surveys on Chinook salmon, contributing to their core program operating five fishwheels along the Nass River.

Partnerships

Links

- Nisg̱a’a: People of the Nass River

Berger, Thomas R. and Frank Calder and Nisg̱a’a Tribal Council - This Place Is Who We Are, Chapter 3

Katherine Gordon - Nisg̱a’a Treaty

Nisg̱a’a Nation - Nisg̱a’a Fisheries Management

Nisg̱a’a Nation - Laxmihl - Annual Report 2002/2003

Nisg̱a’a Nation - Wilp Wilx̱o’oskwhl Nisg̱a’a Institute

Nisg̱a’a Nation - The Saviour Fish: Protecting Nisg̱a’a Connection to Oolichan

Coast Funds - Nisg̱a’a Nation Harvest Agreement

Government of Canada - Fish Monitoring

Province of British Columbia - State of Pacific Salmon

Pacific Salmon Foundation - Ayuuḵhl Nisg̱a’a

Story Maps

Published On October 15, 2025 | Edited On October 15, 2025