In Gwa’yas’dums, the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis are seeing the results of strong, community-led planning and thoughtful investments in infrastructure and services that will support future generations to return home.

Coming Home: Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis Invest in Solar Power, Infrastructure in Gwa’yas’dums

Estimated Reading time

32 Mins

Gwa’yas’dums, located on Gilford Island, is the main village for the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation. Gilford Island is about 382 km2 and is located between Tribune Channel and Knight Inlet off the coast of modern-day British Columbia.

At a Glance

Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation leaders and members have come together around a shared vision for revitalizing the village of Gwa’yas’dums, the Nation’s main community. The village, located on the west side of Gilford Island in what’s known as the Broughton Archipelago, is a small, close-knit community nestled between dense rainforest and shell-laced shoreline.

Since releasing its award-winning comprehensive community plan in 2006, KHFN has invested in new housing, a modern health and administration building, tourism infrastructure, and a 221 kW solar photovoltaic (PV) and 1.1 MWh battery microgrid to deliver clean electricity to the village. The Nation is also working to secure funding and complete complementary projects that will improve access to drinking water, restore and protect the foreshore, and build a sustainable local economy.

These important projects come after decades of underinvestment by colonial governments, which left the community with poor housing, unsafe drinking water, and a lack of access to schools and services. Under these conditions, many people had no choice but to leave, and the village’s population declined. Today, KHFN has 270 members and between 30 and 70 people live in Gwa’yas’dums, depending on the season.

To reverse course, the Nation is working with partners to invest in renewable energy, community infrastructure, and sustainable economic ventures. These efforts are revitalizing Gwa’yas’dums and – most importantly – making it possible for more Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis people to return home.

Gwa’yas’dums

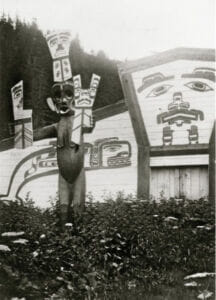

The Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w and Ha̱xwa’mis peoples have lived in the islands and inlets of the south-central coast for thousands of years – since the Great Flood – and have built a strong culture and close ties with neighbouring Nations. Before the two groups amalgamated in 1948, the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w lived mainly on Gilford Island and the Ha̱xwa’mis lived in Wakeman Sound.

Gwa’yas’dums, once a Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w winter village used by the Four Tribes of Kingcome Inlet, is now the main community for Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation (KHFN). To support travel and carry supplies to the community, KHFN operates a water taxi service that connects the village to Alert Bay, Port McNeill, and neighbouring islands in the Broughton Archipelago.

Today, when visitors approach the village by water, they’ll see rows of wood-framed homes hugging the shoreline, roofs topped with glinting solar panels and windows facing out to the ocean. Two buildings stand taller than the rest: the Big House – one of the oldest on the coast – and the Nation’s new health and administration building. Behind the village, thick stands of cedar, hemlock, and fir rise up into the mountains.

From the roar of a distant chainsaw to the scuffle of dogs playing, Gwa’yas’dums village is busy with the sounds of work and family life. It’s mid-August and families who spend the winter months in larger communities have returned home for the season. Teenagers carry snacks and tools, helping uncles and relatives to cut back the brush around the village perimeter and gather firewood for the winter. Visiting tradespeople walk the gravel roads, equipment in hand, heading to job sites at both ends of the village. August fog hangs in the air, holding the smells of cedar, salt water, and construction dust.

Rick Johnson, Hereditary and elected Chief of KHFN, is home for the summer and, in between greeting friends and checking on progress, he pauses to reflect on the change he’s seen in his lifetime.

Born in the village, Chief Rick Johnson was raised by a strong, cultural family and, in his first hour of life, relatives welcomed him to the community by wiping him with precious t’lina eulachon oil. Back then, more people lived in the village, which had a school, housing, and a larger dock – every family had a boat. He remembers the village emptying out in the summertime, “we’d all run up to Rivers Inlet to fish and we’d be up there all summer long. And then they’d come back and our people would go out logging right after that.”

“In this village, we grew up traditionally,” Chief Rick Johnson says. “We know our traditional lines, we know our history, we know our legends, we know our treasure boxes, we know our songs and our language.”

Chief Rick Johnson is now in his sixties and, in the decades since he was a boy, he’s witnessed what can happen when colonial governments underinvest in Indigenous communities: school closures, unsafe drinking water, moldy housing, crumbling roads, poor health care. An injustice that stands in sharp contrast to the sheer volume of wealth extracted from Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis territory.

You see huge barges go past with millions and millions of dollars of our resources.

“You see huge barges go past with millions and millions of dollars of our resources on [them]: beautiful cedar, hemlock, spruce trees. Probably going on to the States or heading over to China to be processed,” he says, gesturing to the shore. “It makes sense to me that, around the 1960s, the school got shut down and there was a big push to get us out of here so that industry could continue to do this without the presence of our people living here.”

In order to access schools, services, and jobs, young families left the village and the population dropped. At one point, Chief Rick Johnson recalls there were only 14 or 15 people living in Gwa’yas’dums, mostly Elders, who he credits for their resolve in maintaining the Nation’s presence in their territory, despite the challenges.

You see our kids that are here now? Some of them may stay. That’s the dream, that’s the hope.

To turn things around, KHFN worked with partners to develop a comprehensive community plan to revitalize Gwa’yas’dums, invest in better housing and local energy projects, and prepare for new economic opportunities.

“This village has been neglected for so long,” Chief Rick Johnson says. And, in that time, the infrastructure gap between Gwa’yas’dums and non-Indigenous communities has widened. “With all the abundance this place holds, it doesn’t make sense that, as a Nation, we’re struggling with inadequate housing, inadequate water, and a lack of schools.”

“So, the rebuild is really important. You see our kids that are here now? Some of them may stay. That’s the dream, that’s the hope.”

Vision for the Future

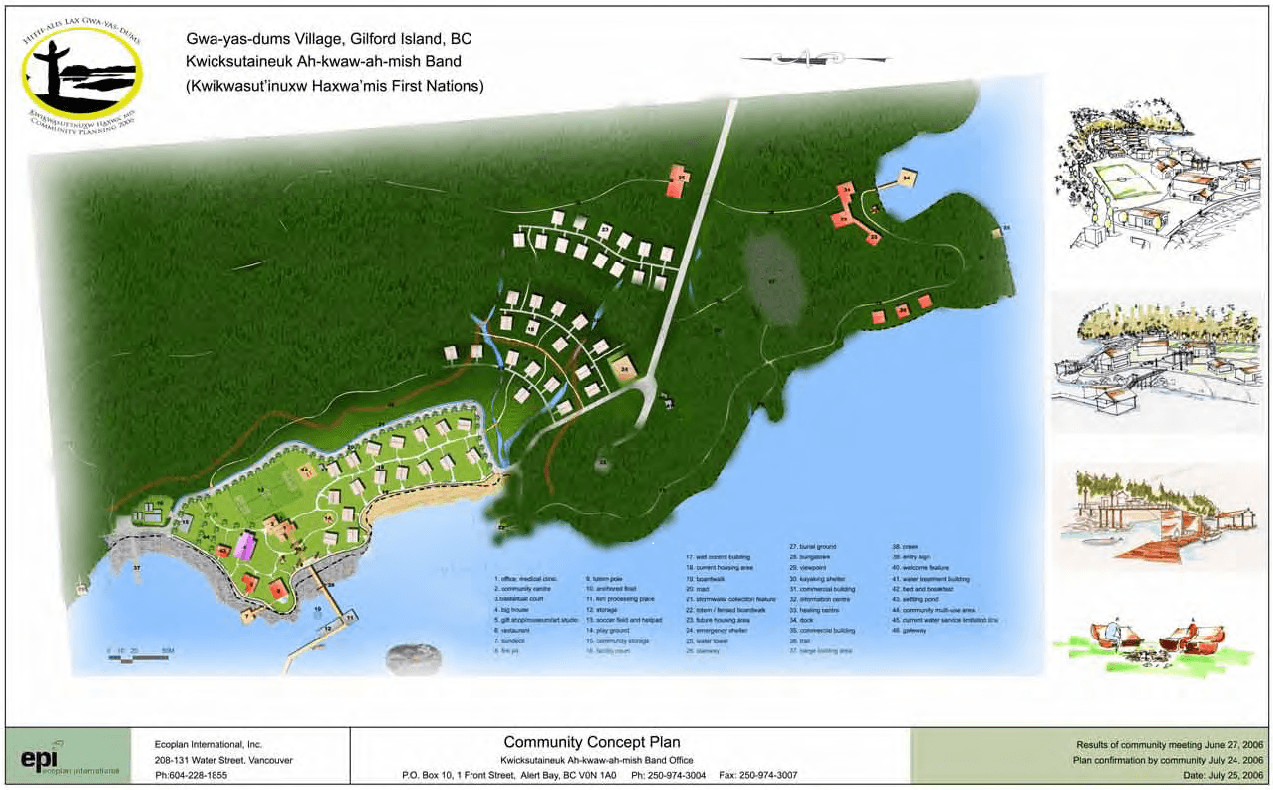

In 2005, Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis members came together to take stock of the community’s infrastructure and build a plan for investing in Gwa’yas’dums so members could come home to live and work in the territory. Through a process called comprehensive community planning (CCP), KHFN hosted community meetings, tours, and workshops to identify issues, challenges, and strengths, then determine options for addressing them.

Through the CCP process, the community created a 25-year action plan to focus on urgent needs like housing, electricity, and water, alongside important priorities like health and healing, education and training, and cultural protection and learning.

Since completing their community plan, KHFN’s current and past councils have made incredible progress, investing in:

- Temporary housing for members to live in while homes are rebuilt.

- 30 new homes, with six more under construction, and planning for a new subdivision.

- A 221 kW solar PV and 1.1 MWh battery microgrid to provide clean, reliable electricity and reduce the need for imported diesel.

- A reverse osmosis chlorination water treatment system for drilled wells.

- A new health and administration building where Chief and Council can meet, Nation staff can work, and healthcare workers can meet with residents.

- Renovations to the 100-year-old Big House to reinforce the structure, lower the floor, and repaint the exterior.

- Acquiring the Echo Bay Marina and Lodge at Ḵ̓wax̱wa̱lawadi, a traditional village site.

- Fibre-optic internet access, as part of the Connected Coast project.

The number one priority is bringing members home and developing a work base.

In 2021, KHFN hired Jamie Pond, a project manager from a mixed First Nations and Irish family, to support economic development and funding applications. With her background in infrastructure projects, strong commitment to community, and sharp sense of humour, Jamie was able to hit the ground running.

“When I first got here, the first thing I did was go through that comprehensive community plan in detail more than once,” Jamie says. “The number one priority is bringing members home and developing a work base.”

After lending her expertise to KHFN’s development of Echo Bay Marina and Lodge, a newly-acquired tourism business on the north end of Gilford Island, Jamie moved into a permanent role as the Nation’s Capital Projects Manager. With the revitalization of Gwa’yas’dums well underway, she’s been busy working with Council to plan projects and secure funding, partnerships, and contracts.

Between supporting the construction of a solar PV and battery microgrid, building out tourism infrastructure at Echo Bay, taking over the completion of the health and administration building, overseeing new housing, obtaining funding for renovations, and planning seawall and water upgrades, her work includes a lot of moving parts and interconnected priorities. Nothing is linear.

“[It] requires a real tic-tac-toe kind of strategy, where we have to sort of look at things like a puzzle, and we have to make the pieces work out.”

Solar PV and Battery Microgrid

One of the biggest puzzle pieces? Electricity in an off-grid community.

When Chief Rick Johnson was a boy, people in Gwa’yas’dums used coal oil lamps for light and wood stoves for heat. Some families purchased small generators for their homes and then, to bring electricity to the whole village, KHFN installed three diesel-powered generators and built a network of power lines.

While the system worked, it came with several drawbacks. When one of the generators needed maintenance, they’d shut it down, disrupting power, before switching to another generator. Residents would often trip the breakers feeding their freezers when the power went out and have to manually reset them.

Another challenge? As Gwa’yas’dums’ population declined, the generator setup was larger than the community needed. Because diesel generators become more efficient with a modest energy load, residents were encouraged to use extra electricity – opening windows in the winter, keeping streetlights on during the day – to keep the generators running well.

It’s dirty, it’s loud. And, of course, the exhaust smells, depending on which way the wind is blowing.

To power Gwa’yas’dums, KHFN was purchasing and burning a significant amount of fuel per year, at a cost of nearly $200,000. Relying on imported diesel left the Nation vulnerable to price fluctuations, spill risks, and transportation delays. In addition to high costs for an inefficient system, community members were also contending with power outages, noise, and air pollution.

“[Diesel] creates a giant environmental footprint,” says Jamie, who estimates the diesel generators emitted about 174.47 tonnes of greenhouse gases each year. “It’s dirty, it’s loud. And, of course, the exhaust smells, depending on which way the wind is blowing.”

To reduce their reliance on diesel and gain more control over their energy, KHFN worked with an engineering company to consider alternatives. After vetting different options, the Nation decided on a solar PV and battery system that could integrate with their existing diesel generators and meet the community’s seasonal energy needs. In the summertime when solar generation is at its highest, Gwa’yas’dums’ population grows to about 70 people. And, in the cloudy, winter months, the population drops to about 30 people.

The first contractor KHFN worked with proposed building a solar farm in an old quarry up the hill, and then bringing electricity into the village site, which increased construction costs. When it became clear that a different approach was needed, KHFN hired Charge Solar, a Victoria-based company that had previously worked with T’Sou-ke First Nation on the design and construction of a solar microgrid.

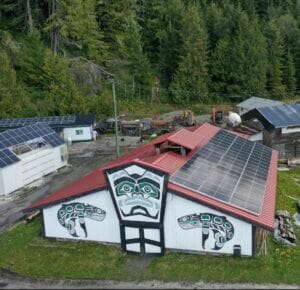

Instead of building a large solar farm in the quarry, community members wanted to add solar panels to the rooftops of the 26 homes and 12 community buildings in the village, including the Big House and the new health and administration building.

“We just listened to the members,” says Ed Knaggs, Vice-President at Charge Solar, who worked with KHFN on the project. “We said, yeah, that’s a really, really good idea. Because you’ve got all that infrastructure already in place, so it’s a lot lower cost [to put panels] on rooftops than it is to build a big solar farm up in a quarry.”

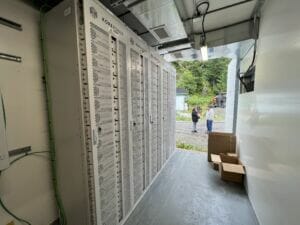

KHFN’s investment is solar has been an incredible success. Today, Gwa’yas’dums is powered by 525 solar panels, each the size of a door, installed on rooftops and along the cliffs near the shore.

Solar and the batteries run the village and the generator is only used for times when the sun can’t keep up.

The panels generate up to 221 kilowatts of electricity, which is fed into a 1.1 MWh battery bank inside a retrofitted shipping container. The batteries can store up to two days of electricity, depending on how many people are living in the village. The diesel generators are still on site and can be turned on to charge the batteries when energy demand outpaces solar production. The system is expected to save over 73,000 liters of fuel each year.

“You’ll fill up the batteries during the day and run the load from the sun. And then, in the evening, there’s no sun available, so it will just draw from the batteries as the load is increasing,” explains Ed. If the batteries don’t last the night or the village sees several cloudy days in a row, the system can start up a generator.

“The idea is that the solar and the batteries run the village and the generator is only used for times when the sun can’t keep up.”

Since the system was completed in July 2023, the diesel generator has been quiet and Gwa’yas’dums has drawn all its power from the sun. By transitioning to solar and reducing the need for imported diesel fuel, KHFN is saving money and residents are enjoying quieter nights, cleaner air, and uninterrupted power.

“It’s operating beautifully,” says Jamie. “It’s worked out far better than we even imagined it would.”

With the new microgrid in operation, the Nation has also begun investing in demand-side measures, like new electric heat pumps in homes, to further lower their energy costs and emissions.

The microgrid’s batteries are under warranty for 20 years though Ed expects the community may be able to extend their lifespan to 40 years or longer.

It’s been such a positive uplift for this community.

Flexibility is another advantage to solar, Ed says. The solar panels are independent and interchangeable so, if one gets damaged, it can be easily replaced. Or, if the community needs more capacity later on, they can always add more panels to the system. Because the system was installed by KHFN members, the community has the knowledge and skill to maintain the system for years to come.

“It’s a little bit boring,” Ed jokes. “One of the problems with solar is that people forget that they have solar because it just sits there and works. It’s not like something that’s, you know, noisy and requires maintenance, so that it loses its luster over time.”

For a community that’s had to rely on diesel for electricity, the solar-battery microgrid has been a game-changer. With the extra power now secured, KHFN is exploring new possibilities, like building a freezing and processing plant to support local fisherman.

“It’s been such a positive uplift for this community,” says Chief Rick Johnson. “This solar power is huge and it’s a step in the right direction for us.”

Bringing the Next Generation Home

Between the solar and battery microgrid system, the new health and administration building, and purchasing Echo Bay, the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis have already achieved so much. Yet there is still more work to do.

Drinking water has been a challenge in Gwa’yas’dums for as long as Chief Rick Johnson can remember. When he was a boy, the village relied on cedar water that flowed down from higher elevations. About a third of the village’s visitors had allergic reactions to the water and, in that time, the water made it challenging to retain teachers and health workers.

To supply fresh water to the village, KHFN and the federal government tried drilling wells. Yet, every time a new well was drilled, salt water and pollutants would seep in, contaminating the water, corroding pipes, and damaging hot water tanks, which exacerbated poor housing conditions in the village. After drilling seven wells and finding saltwater intrusion seven times in a row, the Nation continued to work with Indigenous Services Canada to invest in a small reverse-osmosis water treatment system. While the treatment system has had improvements, the water in Gwa’yas’dums still has a strong salty taste and isn’t good to drink. For health and safety reasons, residents rely on bottled water for drinking and cooking.

“After 20 years of being on bottled water and struggling with a system that hasn’t worked, I think it’s time that this community be afforded the right to the same quality water as anybody else experiences,” says Jamie. With the support of Council and community members, she’s commissioning a feasibility study to assess options and costs for piping water from a high-elevation lake further inland.

Beyond drinking water, in order for young families to stay in the village year-round, children will need a school and working-age adults will need access to jobs and services.

Two decades ago, children in Gwa’yas’dums were transported by boat to Echo Bay, which had a small school. When the school closed in 2008, families were forced to move away from the village. And, in the decades that followed, declines and consolidation in forestry and fishing operations reduced the quality of jobs and opportunities available nearby.

The Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis are now looking to tourism to create jobs for their members and share their peoples’ history and culture with visitors.

“People won’t come home unless there’s an economy…tourism is the future here,” says Chief Rick Johnson. In 2020, the Nation purchased Echo Bay Marina and Lodge, an established business on the north side of the Gilford Island, near the traditional village of Ḵ̓wax̱wa̱lawadi. Along with the resort and docks, KHFN purchased 100 acres of adjacent property.

“Re-claiming ownership of this land within our traditional territory provides more than employment and economic development opportunities for Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis people,” Chief Rick Johnson said in a news release announcing the purchase. “This community-driven initiative gives us more decision-making power in Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis territories and builds on our goal of self-determination.”

When we have possibilities, then we have hope.

Since the purchase, KHFN has developed an interpretive trail, replaced the main dock fingers with robust metal fingers, invested in a new commercial kitchen at the lodge, and plans to open new campgrounds, create skills training opportunities for members, and develop a second solar-powered microgrid to power the lodge and marina.

Through the Connected Coast project, both Gwa’yas’dums and Echo Bay will have access to high-speed internet through newly-installed undersea fibre-optic cable. Once all the homes and businesses are connected, the Nation could establish a virtual school for children in the community, Jamie says, and, in time, demonstrate the case for building a new, physical school on Gilford Island.

With additional land, high-speed internet, and access to a clean, stable electricity supply, the Nation is considering other economic opportunities, like a data storage facility or supports for members to work remotely.

“When we have possibilities, then we have hope,” says Chief Rick Johnson. “We’re building the community, the capacity, and the resources to tap into [a new economy.]”

Everything Depends on Everything Else

In Gwa’yas’dums, the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis have a strong vision and are making commendable progress.

The Nation has been steadfast in its commitment to protecting important cultural treasures – the Big House, harvesting sites, and traditional villages – while also investing in the needs of current and future generations.

“We’re overworked and underpaid,” Chief Rick Johnson admits, crediting the hard work and ingenuity of Council members – past and present – and staff members, who often go beyond their job descriptions to deliver on community priorities. “We improvise. Whatever little we get, we try to maximize.”

In her work on capital projects, Jamie juggles grant applications and construction timelines to maximize value to the Nation. As an example, KHFN is planning a seawall that includes the recovery of lost foreshore, construction of a boardwalk, and protection for a new bioengineered sloped shoreline. Jamie knows that hauling rock from the quarry, blasting, and bringing in heavy equipment will damage Gwa’yas’dums’ pockmarked gravel roads. To avoid repairing the roads twice, KHFN is holding off on roadwork until the heavy equipment has completed its work.

Everything is interconnected, and everything depends on everything else. And that’s why I call it a puzzle.

For more members to move home, the Nation is building new housing, and using single-wide homes to house residents waiting on their new homes to be completed. With limited land suitable for development in the main village, KHFN is planning a new subdivision on the lower end of the reserve. That new subdivision will require more electricity, Jamie says, and the Nation is considering a small hydropower system that could use the same route and access roads as a project to pipe in fresh water from a high-elevation lake.

“With the micro grid being very strong in the summer, we thought a hydro system could complement that and we would be guaranteed full power in winter and full power in the summer,” says Jamie. “Everything is interconnected, and everything depends on everything else. And that’s why I call it a puzzle, rather than a linear process.”

By using their community plan as a guide and seizing on opportunities, the Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis are demonstrating how a small Nation can come together to create changes that grow from one generation to the next.

“We’re standing on the shoulders of greatness,” Chief Rick Johnson says, acknowledging the previous elected Chief, Bob Chamberlin, who worked with Council to create the comprehensive community plan and begin revitalizing the village. In time, future generations of Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis will continue this important work, adding to the community.

Through the Coast Economic Development Society, Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation invested $233,673 in 2021 towards the cost of a new solar and battery microgrid for Gwa’yas’dums.

Online Resources

- Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation

Our Future: Ongoing Projects - Charge Solar

Charge Solar Unveils KHFN Solar Project: 220kw System Offsets 73,000 Liters of Diesel Annually for Kwikwasut'inuxw Haxwa'mis First Nation - Charge Solar

Empowering Sustainability for KHFN First Nations - Island Coastal Economic Trust

Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation’s Steady Path to Economic, Social, and Cultural Rebuilding - EcoPlan International

“Hith Alis Lax Gwa’yas’dums”: Moving from crisis to hope at Gwa’yas’dums Village, Gilford Island, BC (A Story of Comprehensive Community Planning) - Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw Tribal Council

Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Ha̱xwa’mis First Nation

Published On September 11, 2023 | Edited On October 9, 2024