Estimated Reading time

4 Mins

Haisla Nation Restoring Riparian Ecosystems

This article first appeared in the September 2018 issue of Dootilh and appears courtesy of the Haisla Nation.

There’s a silent but urgent battle which takes place in the riparian stream-side forests near Kitimat. The war pits hearty, deeply rooted coniferous trees—such as spruce and cedar—against the feisty alder.

The conflict is actually better understood through history rather than through the study of how trees work.

In the mid-to-late parts of the 20th century, logging efforts in BC and particularly along the coast of BC, were not as sympathetic to forest renewal as they are today. Companies at the time would clear trees straight to the banks of rivers.

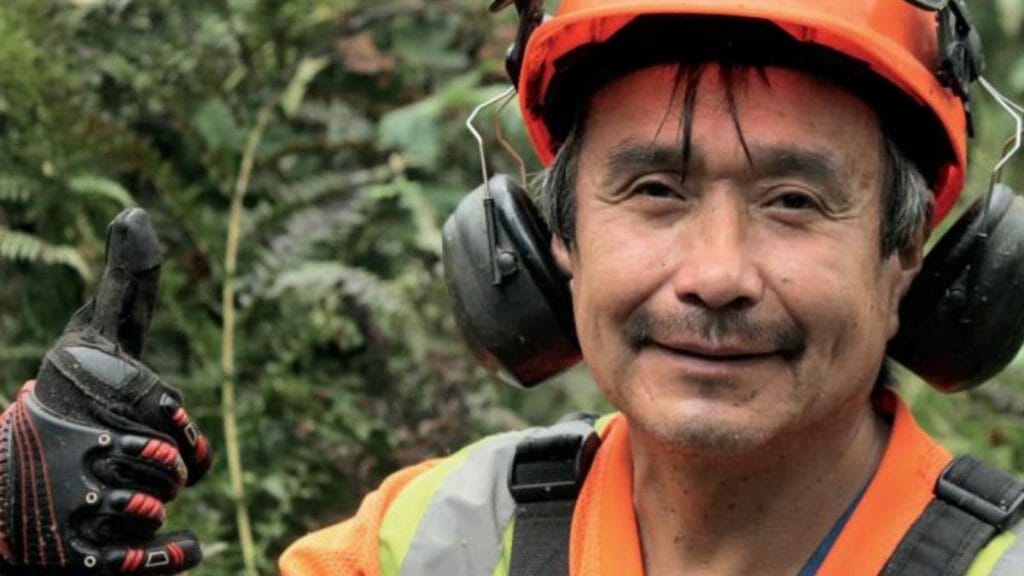

In all there are eight Haisla members employed and working on the project from April through November.

As you may now know, tree systems are vital to healthy watersheds. From erosion control and stream bank stability to the creation of salmon habitat, clear-cutting activities right to the stream bank hurt local watersheds, including many throughout Haisla territory.

Through Haisla Nation Council, riparian restoration efforts are underway to bring these riverbank ecosystems back to the healthy levels that were there prior to logging, and restoring salmon and wildlife habitat.

Now in its fourth year, the riparian restoration project has handled restoration efforts at Humphrey’s Creek, Lone Wolf Creek, and today is active along the Nalbeelah Creek.

The work is guided under the supervision of Bart Simmons (m. Eng.) and Eri Foster of Quillicum Environmental Services Ltd. His BC Forest Council “SAFE” certified team oversees the Haisla crew which is clearing brush and cluster planting spruce under alder in areas where there is no conifer stocking, or undertaking conifer release in stands with suppressed conifers growing underneath alder or thinning overstocked riparian conifer stands.

All these treatments allow the rapid growth of either spruce seedlings or suppressed spruce and cedar to create large, deeply rooted trees in as short a time as possible that can help re-stabilize the stream-banks in the medium-to-long term to withstand the pressures of flood flows in high rain events.

In all there are eight Haisla members employed and working on the project from April through November.

So why are the alders so much worse than spruce or cedar trees when it comes to riverbanks?

The short answer is alder roots just aren’t strong enough. That is, their roots aren’t as large and complex and so they don’t hold together the riverbank as strongly in high flood events.

The result is the high flood flows cause bank erosion as the small rooted alder trees are eroded off of the bank and fall into the stream leaving large cuts in the banks, and also affecting the flow of the river from alder debris that has eroded off the stream bank. This alder debris fills up in rivers and can divert the water flow itself. Additionally, the eroded soil and rocks from the stream banks fall into the river adding large quantities of sediment that can clog salmon spawning beds and widen the river considerably and pools once rich with salmon are filled up with this eroded sediment from the stream banks.

The project is a double win by improving riparian stream-side ecosystems needed by the salmon for decades to come, and also providing employment for Haisla members.

So what’s the solution?

Sprucing up the riparian environment!

It starts with the crew cutting down sections of brush to create small clusters. Then, with a Pulaski axe in hand, the ground is dug up and the roots of the brush is cleared away.

With that room to breath, the spruce are planted in clusters. Without the competition and crowding, the planted spruce trees have a good chance for growth. Suppressed spruce that were already growing under an alder canopy are released in a conifer release strategy where a portion of the alder within five metres of a suppressed spruce are felled or girdled to allow the suppressed spruce room to grow and flourish unimpressed by the nearby alder tree.

Haisla Nation Council has funded the project through forestry-related income. [Learn more about the creation of Coast Funds and the Great Bear Rainforest agreements here.]

The project is a double win by improving riparian stream-side ecosystems needed by the salmon for decades to come, and also providing employment for Haisla members. Creating a more sustainable riparian forest that helps to restore salmon habitat is in everyone’s interest.

Coast Funds is proud to support the Haisla Nation’s conservation and stewardship projects, including the riparian restoration projects at Lone Wolf and Humphreys Creek. Learn more about First Nations-led, Coast Funds-supported stewardship and conservation projects here.