Estimated Reading time

10 Mins

Guides and Guardians: Blending Ecotourism and Stewardship Training to Build a Conservation Economy

Guardians and Indigenous ecotourism guides have a lot in common. In both roles, trained professionals rely on their knowledge of a Nation’s territory, wildlife behaviour, and stewardship practices in order to carry out their work to guide visitors and monitor territory.

Frank Brown, a Haíɫzaqv hereditary Chief and experienced leader in stewardship operations and economic development, sees as opportunity to blend training in stewardship and ecotourism, to prepare Indigenous people on the coast for careers in the conservation economy.

In 2016, Brown helped design the Indigenous Ecotourism Education Program (IEEP), which supports Indigenous learners to acquire the skills and credentials needed to succeed in the Indigenous ecotourism sector. To develop the seven-month program, the Heiltsuk Tribal Council partnered with Vancouver Island University and North Island College. Today, courses are delivered online and in-person, and students complete work placements in communities that host Indigenous tourism experiences.

“Through partnering with the academy, this program bridges technical skills requirements with local knowledge and Indigenous world views in an innovative delivery model, providing a unique and transformative experience,” says Brown.

After five years of delivering the program, organizers completed an evaluation and identified opportunities for the program to grow and evolve to meet the needs of the next generation of learners.

Growing the Conservation Economy

Along the coast, many First Nations are building sustainable local economies by building or acquiring resorts, which attract visitors for guided tours, wildlife viewing, and cultural experiences. As an example, the Heiltsuk Tribal Council recently purchased Shearwater, a resort and marina on Denny Island, and is finding creative ways to incorporate Haíɫzaqv culture, traditions, and hospitality into the resort’s business model.

Indigenous-Owned Resorts in the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii:

- Spirit Bear Lodge, owned by Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation

- Pierre’s at Echo Bay Lodge and Marina, owned by Kwiḵwa̱sut’inux̱w Haxwa’mis First Nation

- Shearwater Resort and Marina, owned by the Heiltsuk Tribal Council

- Knight Inlet Lodge, owned by Na̲nwak̲olas Council

- Hiellen Longhouse Village, owned by Old Masset Village Council

- Haida House, owned by HaiCo (Council of the Haida Nation)

- Kwa’lilas Hotel, owned by Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nation

With resort ownership, many of these First Nations also gain access to docks, boats, fuel stations, and meeting spaces – which can be used by their stewardship departments.

In many ways, Brown says, there’s a lot of overlap in the work and skillsets of Guardians, who monitor and protect territories, and guides, who bring guests out on the territory to view wildlife, see archaeological sites, and learn from storytellers. To be successful in their work, guides and Guardians must be intimately familiar with their Nations’ territory, history and culture, the wildlife it holds, the cultural features, and the inherent laws and knowledge systems that support its management.

Building on the success of the training that’s already offered for ecotourism and stewardship, Brown envisions a new designation for a combined Guide/Guardian who can support the growth of the conservation economy.

“In these times of ecological and social uncertainty, it’s one thing to conserve our territorial lands and water to maintain our stewardship commitments, but another to create meaningful employment and economic opportunities that can sustain our people and territories for future generations,” says Brown. “To me, this combined credit program can help build the conservation economy while preserving biodiversity as a strategy to mitigate climate change.”

Revitalizing Traditions

Ecotourism and large events create opportunities for Indigenous peoples to share their history and culture.

As part of Expo 86, Brown organized a 500-kilometre canoe journey from Wáglísla Bella Bella to Vancouver. The Expo’s theme was communication and transportation and, as Brown explains, the glwa (ocean-going canoe) is the original vessel for communication and travel along the Pacific coast.

“Glwa was a powerful teacher that transported us back in time to understand the wisdom of the ancestors. It not only connected us to the water in a traditional way; it provided insight into ecological and cultural knowledge that was nearly lost,” he says.

Building on the success of the Expo 86 journey, the Heiltsuk Tribal Council hosted the first Qatuwas (people gathering together) event in 1993, which brought 3,000 Indigenous people and nearly thirty canoes from throughout the Pacific Coast to Wáglísla Bella Bella for a seven-day celebration. Following the inaugural 1993 Qatuwas gathering other First Nations and Native American Tribes on the coast took turns hosting what became known as Tribal Canoe Journeys.

The Haíɫzaqv again hosted a Qatuwas event in 2014, bringing 5,000 people and more than fifty canoes to the community for seven memorable days of gathering, ceremonies, and feasting.

To celebrate three decades of canoe journeys, the Heiltsuk Tribal Council, SeeQuest Development Co., and Greencoast Media produced Sacred Journeys, a multimedia exhibit on the revival of canoe culture in the Pacific Northwest, which is on now at Science World in Vancouver.

Through initiatives like the Tribal Canoe Journeys and back to the land programs, First Nations are celebrating their language and traditions, while helping settlers and visitors to better understand First Nations histories and cultures.

Preparing Indigenous People for Jobs in Ecotourism and Stewardship

At the 2014 Qatuwas event, the Haíɫzaqv saw the potential for ecotourism and large events to boost the local economy, create family-supporting jobs, and contribute to the revitalization of culture, language, and stewardship traditions.

As a legacy of Qatuwas, the Haíɫzaqv wanted to increase their and other First Nations communities’ capacity for hosting and welcoming visitors to their territories. To build that capacity, the Haíɫzaqv partnered with Vancouver Island University (VIU) and North Island College to develop the Indigenous Ecotourism Education Program, a seven-month program for students from coastal communities. Brown serves as the program’s advisor and cultural coordinator.

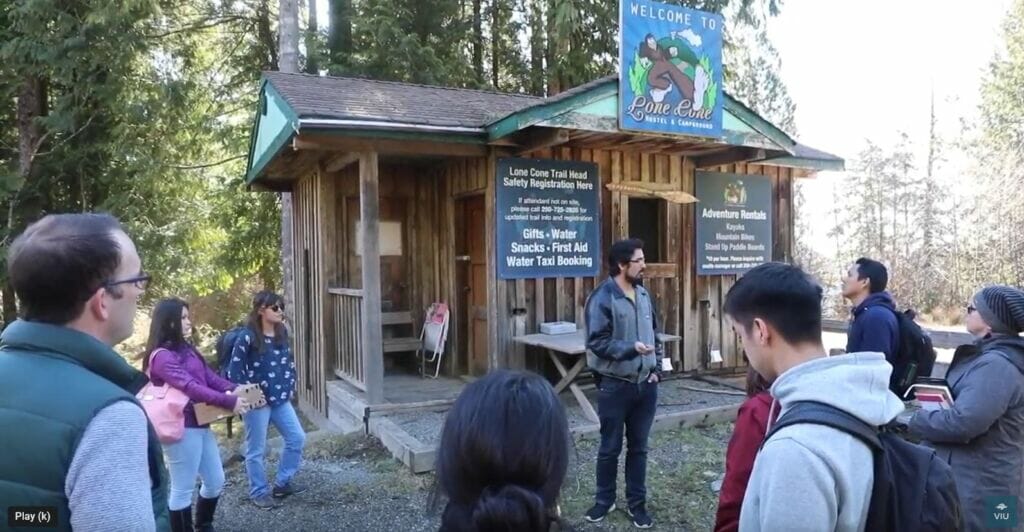

Through IEEP, students acquire knowledge and skills via field school, experiential education, online, classroom, and community-based learning. The program covers a wide range of topics, including guiding, interpretative program design and paddling, tourism business management, field safety and first aid, marketing, economic development, and culturally-safe sharing and storytelling.

“All these young people gain an understanding of the tourism industry as a sector of the economy,” says Brown, who credits the program’s academic, applied, and community-based approaches for its success.

In 2021, IEEP partners worked on a five-year evaluation of the program and its impacts. They found that the program did an exceptional job of delivering experiential tourism training, supporting employment, and contributing to students’ personal growth. The evaluation also helped to reveal some challenges in delivering a truly Indigenous-led program and a need for additional flexibility and supports to support learners, some of whom are the first in their family to enroll in post-secondary education.

To me, this combined credit program can help build the conservation economy while preserving biodiversity as a strategy to mitigate climate change.

Before moving back to Bella Bella to coordinate Qatuwas 2014, Brown served as Director of Land and Marine Stewardship for Coastal First Nations (CFN) and was involved in developing a pilot project for Guardian training. Through a partnership with VIU and other First Nations, CFN helped to design and deliver the Stewardship Technicians Training Program (STTP), which prepares Guardians for their role as ecosystem stewards.

Next Steps

Building on the success of the stewardship (STTP) and ecotourism (IEEP) programs, Brown is working with Vancouver Island University to develop a blended program that prepares learners to manage their territories and build businesses and community capacity to deliver exceptional ecotourism experiences for thoughtful visitors.

The program is under development and Brown expects more details to be available in the coming months.